Questions abound in Malaysia on whether new Covid-19 lockdown came too late

Sign up now: Get insights on the biggest stories in Malaysia

A soldier stands guard at a roadblock to enforce lockdown measures in Kuala Lumpur, on Jan 13, 2021.

PHOTO: REUTERS

KUALA LUMPUR - On Dec 5, despite having recorded over 1,000 new Covid-19 cases daily for most of the past month and more than 100 deaths in the same period, Malaysia decided to reopen interstate travel two days later.

That led to year-end holidaymakers flocking to popular spots such as Penang and Langkawi, which predictably registered a spike in cases.

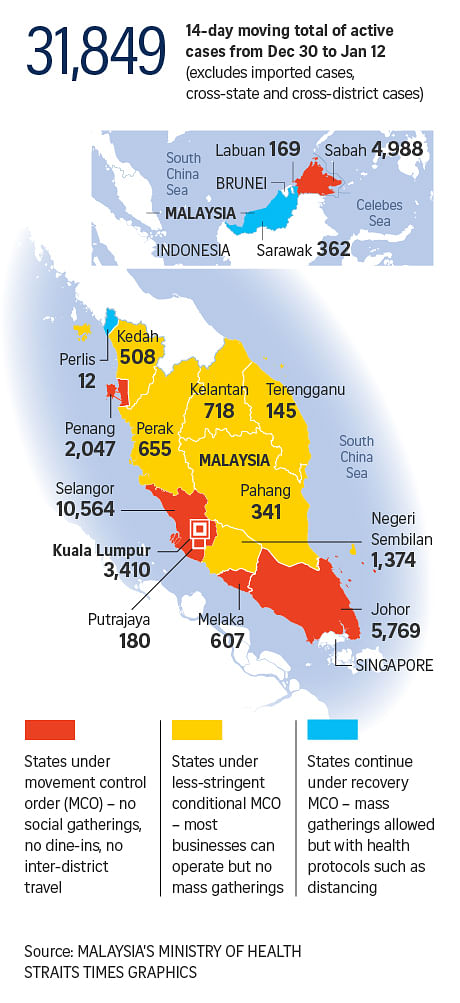

Since then, daily infections in the country have averaged close to 2,000, with a record high of 3,309 on Tuesday (Jan 12). The total number of active cases has tripled to 32,377 as of Wednesday, which is more than the 28,674 beds reserved for Covid-19 patients in public hospitals and quarantine centres.

With the Health Ministry left with no choice but to trust those with mild symptoms to practice self-isolation at home - albeit with the risk of them transmitting the coronavirus to family members and neighbours - the return of the strict movement control order (MCO), first introduced last March, was inevitable.

Director-general of Health Noor Hisham Abdullah warned last week that based on existing trends, daily cases could hit 8,000 by mid-March and breach the five-figure mark in April.

But questions abound on whether the two-week MCO, which began on Wednesday in five states and all three federal territories, has come too late.

"It would have been best to impose an MCO on Sabah after the rapid rise in cases because of the state elections in September, but because there was no MCO, the cases have dragged on and on," the government's Covid-19 Epidemiological Analysis and Strategies Task Force chairman, Professor Awang Bulgiba Awang Mahmud, told The Straits Times.

In the Klang Valley - the epicentre of the crisis - intensive care units (ICU) for Covid-19 patients at several hospitals are full, meaning doctors will have to make "live-or-die" decisions for those critically ill. The Sungai Buloh Hospital, the main treatment centre for cases in the Klang Valley, has been opening up new ICU wards every week.

"There are cases that can't be warded because all the hospital beds are full. Even cases needing ventilators in ICU are forced to be managed in emergency zones," said Dr Alzamani Mohammad Idrose, an emergency and trauma specialist.

Tan Sri Dr Noor Hisham also acknowledged on Wednesday that the government had to supplement manpower without which it cannot add more beds.

The increasing strain has resulted in no zero-death days since Dec 4, with a record 16 fatalities on Jan 8.

Some 435 people have died since Sept 12 - the day campaigning for the snap Sabah state polls began - compared to just 128 in the previous nine months.

The poll was triggered after Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin's Perikatan Nasional (PN) pact tried to oust Parti Warisan Sabah president Shafie Apdal as chief minister, forcing the latter to convince the governor to dissolve the state legislature.

The election went ahead despite new clusters mushrooming in the eastern coast of Sabah which the authorities claimed were caused by illegal migrants entering through the porous seaboard. But as politicians and voters shuttled in and out of the state, Covid-19 soon took root nationwide.

While both sides of the political divide pointed the finger at each other for forcing Sabahans to the ballot box, public confidence in the government's ability to handle the prolonged outbreak wavered.

Opinion polls carried out in July and August saw a whopping 93 per cent of respondents approving of the government's handling of the pandemic. By October, it had slipped to 63 per cent.

Questions have since been raised about loose protocols as infections repeatedly hit new highs, with some even suggesting that the lifting of interstate travel was a ploy to allow the Muhyiddin administration to seek emergency powers and suspend Parliament amid growing doubts over PN's already shaky grip on power.

"Wait. Did they purposely allow interstate travel before so the case would spike thus making it easier for PM8 (Muhyiddin) to ask for Darurat (emergency) declaration from Agong?" said @nizambakeri in a tweet that was shared 3,000 times.

But Malaysians also need to look at themselves in the mirror. It is true that politicians and other prominent members of society flouted the rules meant to reduce the risk of transmission but largely got away with a slap on the wrist.

However, the number of people caught in breach of the same rules - such as failing to wear masks, practice social distancing and contact tracing, or participating in prohibited entertainment activities - has also been on the increase.

Some 3,304 were detained by police in the first week of 2021 compared to 2,974 (not including those caught crossing district or state borders) from Nov 9 to 15, the first week when the Conditional MCO was put in place in most states.

This lackadaisical attitude by some endangers others. Dr Noor Hisham said the MCO would last a maximum of four weeks to limit the economic fallout. Experts, though, believe that six to 12 weeks will be needed to bring Covid-19 under control.

"The MCO needs to be strict enough and long enough for it to work. A half-baked MCO will have no real effects on the contact rate. I think we will not see a sustained decline after two weeks. It might take up to 12 weeks for this to be comfortably low enough," said Prof Awang Bulgiba.

He said: "The first time around, we bought time with MCO 1.0 but squandered it and did not address many issues like migrant workers, better data analysis, scenario planning, revision of Pandemic Preparedness Plan and so on. If we do not do something about these issues, then the time we are buying with MCO 2.0 will be squandered again."