Not just India: New Covid-19 waves deluge developing countries

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Nepal is seeing hospitals quickly filling up and running out of oxygen supplies.

PHOTO: REUTERS

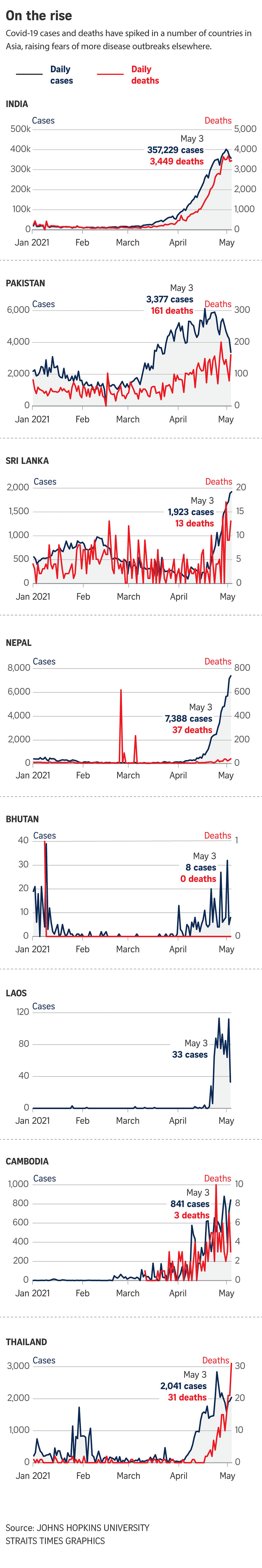

BANGALORE (BLOOMBERG) - It is not just India. Fierce new Covid-19 waves are enveloping other developing countries across the world, placing severe strain on their healthcare systems and prompting appeals for help.

Nations ranging from Laos to Thailand in South-east Asia, and those bordering India such as Bhutan and Nepal, have been reporting significant surges in infections in the past few weeks. The increase is mainly because of more contagious virus variants, though complacency and lack of resources to contain the spread have also been cited as reasons.

In Laos last week, its health minister sought medical equipment, supplies and treatment as cases increased by more than 200 times in a month.

Nepal is seeing hospitals quickly filling up and running out of oxygen supplies.

Health facilities are under pressure in Thailand, where 98 per cent of new cases are from a more infectious strain of the pathogen, while some island nations in the Pacific Ocean are facing their first Covid-19 waves.

Although nowhere close to India's population or flare-up in scope, the reported spikes in these handful of nations have been far steeper, signalling the potential dangers of an uncontrolled spread.

The resurgence - and first-time outbreaks in some places that largely avoided the scourge last year - heightens the urgency of delivering vaccine supplies to poorer, less influential countries and averting a protracted pandemic.

"It's very important to realise that the situation in India can happen anywhere," said Dr Hans Kluge, regional director at the World Health Organisation for Europe, during a briefing last week. "This is still a huge challenge."

Ranked by the change in newly recorded infections in the past month over the previous month, Laos came first with a 22,000 per cent increase, followed by Nepal and Thailand, both of which saw fresh caseloads skyrocketing more than 1,000 per cent on a month-on-month basis.

Also on top of the list are Bhutan, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname, Cambodia and Fiji, as they witnessed the epidemic erupt at a high triple-digit pace.

"All countries are at risk," said infectious disease epidemiology professor David Heymann at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. "The disease appears to be becoming endemic and will therefore likely remain a risk to all countries for the foreseeable future."

On May 1, India reported a record 401,993 new cases in the prior 24 hours, while deaths touched a new high of 3,689 the following day. The nation's hospitals and crematoriums are working overtime to cope with the sick and the surging number of deaths.

Compounding the crisis, healthcare facilities are also facing a shortage of medical oxygen, unable to treat distressed patients with coronavirus-infected lungs gasping for air at their doorsteps.

The abrupt outbreak in Laos - a place that had recorded only 60 cases since the start of the pandemic until April 20 and no death to date - shows the challenges facing some of the landlocked nations. Porous borders make it harder to clamp down on illegal crossings though entry is technically banned.

Communist-ruled Laos has ordered lockdowns in its capital Vientiane and banned travel between the capital and provinces. Its health minister has contacted neighbours like Vietnam for assistance on life-saving resources.

Nepal and Bhutan have seen cases erupt, in part due to returning nationals. Nepal, which has identified cases of the new Indian variant, has limited resources to combat the virus.

'Very serious'

The situation is "very serious", according to Professor Ali Mokdad, chief strategy officer for population health at the University of Washington. "New variants will require a new vaccine and a booster for those already vaccinated - they will delay the control of the pandemic."

Prof Mokdad said the economic hardship of poorer countries make the battle even tougher.

Thailand, which had been seeking to revive its ailing tourism industry, just reintroduced a two-week mandatory quarantine for all visitors. A government forecast for 2021 tourism revenue was cut to 170 billion baht (S$7.26 billion), from January's expectations for 260 billion baht. With the country's public health system under pressure, the authorities are trying to set up field hospitals to accommodate a flood of patients.

About 98 per cent of cases in Thailand are of the variant first identified in Britain based on a sample of 500 people, according to Professor Yong Poovorawan, chief of the Centre of Excellence in Clinical Virology at Chulalongkorn University.

Red zone

In Cambodia, since the beginning of the current outbreak, more than 10,000 locally acquired cases have been detected in more than 20 provinces. The Cambodian capital Phnom Penh is now a "red zone", or a high-risk outbreak area.

In Sri Lanka, the island nation at the southern tip of India, the authorities have isolated areas, banned weddings and meetings, and closed cinemas and pubs to cap a record spike following last month's local New Year festivities. The government says the situation is under control.

Across the oceans in the Caribbean, Trinidad and Tobago announced a partial lockdown after the country's daily cases hit a record high, closing restaurants, malls and cinemas until late May. The case count in the latest month is about 700 per cent more than the previous month's.

That high level of increase is also seen in Suriname, on the north-eastern coast of South America. Cases in April rose more than 600 per cent from those in March.

After staying relatively Covid-19-free thanks to strict border controls, some of the Pacific island nations are now seeing their first wave. Cities in the tourist hot spot of Fiji have gone into lockdown after the wider community contracted the virus from the military.

"The recent rise in recorded cases throughout the Pacific reveals how critical it is to not just rely on strong borders but also to actually get vaccines into these countries," said Mr Jonathan Pryke, who heads research on the Pacific region for the Lowy Institute, a Sydney-based think-tank.

"India is a shocking warning to this part of the world about how quickly this pandemic can spiral out of control."

There is a duty for developed countries, recovering from the pandemic thanks to rapid inoculations, to contribute to a more equitable global distribution of vaccines, diagnostic tests and therapeutic agents including oxygen, according to London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine's Prof Heymann.

Dr Jennifer Nuzzo, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Centre for Health Security in Baltimore, said the world has not seen a concerted global response yet, and that is a concern.

Getting back to pre-2020 normalcy "really depends on helping countries gain control of this virus as much as possible", she said. "I really hope countries can look within themselves and figure out what they can do to help."