Flood-friendly homes: How Jakartans are making peace with rain

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Mr Aditya Megantara pointing to the space between his house and the ground.

ST PHOTO: KARINA TEHUSIJARANA

- Jakarta faces perennial flooding and President Prabowo plans a giant sea wall to mitigate this issue, but it will only start in September 2026.

- Aditya Megantara built an "anti-flood" stilt house, inspired by a documentary, allowing water to flow underneath, feeling drier and reducing colds.

- Architect Yu Sing champions flood-resilient designs, advocating "sponge city" concepts and community-focused solutions, unlike land raising.

AI generated

JAKARTA – Flooding is a perennial problem in Jakarta, and 2026 is no different, with near-constant rain since the start of the year culminating in severe flooding on Jan 22 that displaced at least 1,600 people.

Several ambitious projects have been proposed over the years, the latest being Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto’s giant sea wall, set to begin construction in September and planned to encompass the whole northern coast of the island of Java.

Meanwhile, many Jakartans have turned to smaller-scale solutions, including redesigning their homes to better adapt to flooding.

Documentary film-maker Aditya Megantara is among them. Mr Aditya, 40, has lived in the flood-prone area of Pondok Bambu in East Jakarta since childhood. He said that almost every time it rained heavily, his house would flood.

“So I had this dream, that if I ever built a house I would figure out a way for it not to flood,” Mr Aditya told The Straits Times on Jan 25.

His dream finally began to take shape in 2020, when he was working on a documentary about the massive flooding that struck Jakarta around the start of the year. Part of the documentary highlighted a house in Kelapa Gading, North Jakarta, that was specifically designed as an “anti-flood” house.

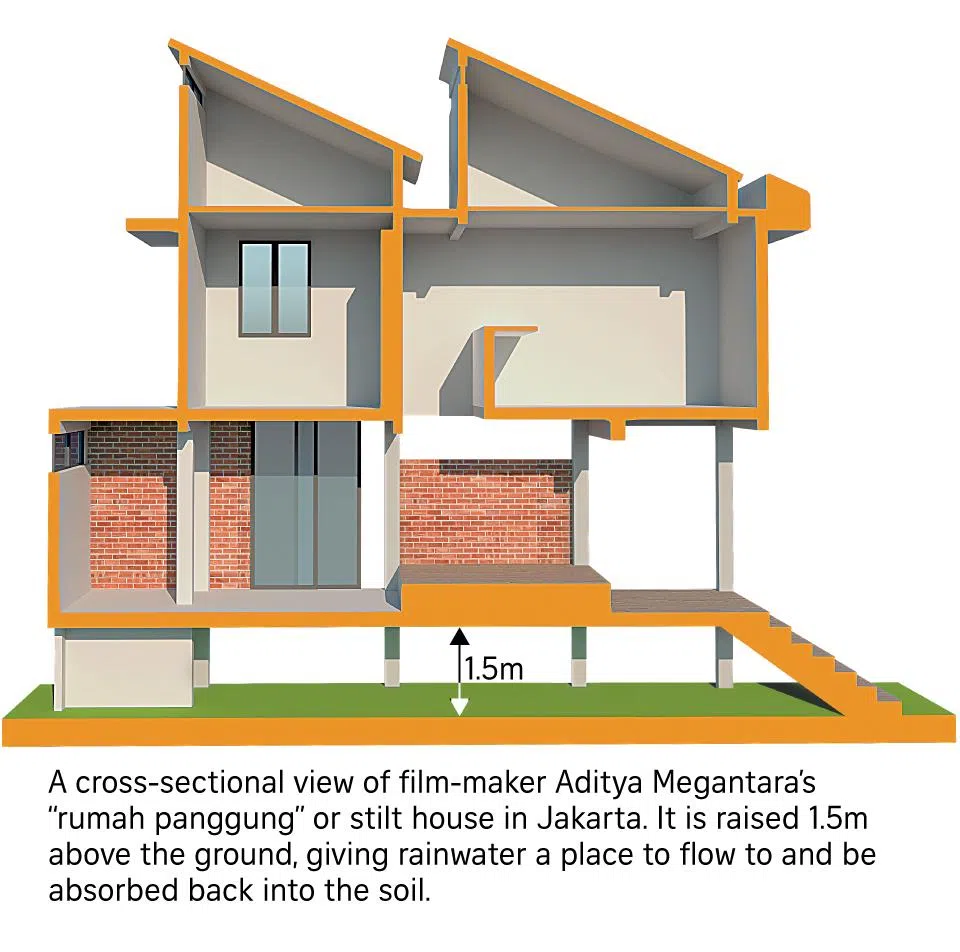

With its floor raised above ground, it is a modern take on the traditional “rumah panggung” – stilt houses once common in the coastal areas of Jakarta and throughout Indonesia.

At the time, Mr Aditya was already planning to build a house on an empty lot behind his childhood home. But after working on the documentary, he engaged the architect of the Kelapa Gading house to design a similar “rumah panggung” for him.

Rather than raising the floor to avoid flooding, Mr Aditya left the 1.5m space between his house and the ground empty. This allows water to flow beneath and be absorbed back into the soil instead of merely diverting it elsewhere.

Since completing the house in 2023, there have been no major floods in the area until last week, when water inundated the street outside; even so, Mr Aditya has noticed other advantages.

“Because the house is not touching the ground, it feels drier and less damp. So I feel like I’ve had fewer colds,” he said.

Flood waters entered Mr Aditya Megantara's old house in January 2020.

PHOTO: ADITYA MEGANTARA

Mr Yu Sing, the house’s architect and founder of architectural design studio Akanoma, said the design allows home owners to respond to flooding without “only saving themselves”.

“A lot of housing developments in Jakarta claim to be flood-free, but it’s only because they’ve raised the land so high,” he told ST. “They might avoid flooding for a while, but they end up causing floods in lower areas.”

He said he came up with the idea as a way to build a house that would not flood, while also providing a catchment for the surrounding areas.

“In the long term, we hope that more and more houses follow this example, so that even if even more areas become flooded, the houses will be safe, and there will be more room for water infiltration,” he said, adding that he has already designed five houses in the last 10 years with the concept in Greater Jakarta.

Assistant Professor Herlily, who specialises in architecture and urban planning at the University of Indonesia, said that houses like Mr Aditya’s should be part of a wider push to turn Jakarta into a “sponge city” – a city designed to better absorb heavy rainfall.

She added that while stilt houses are a good individual solution to the flooding problem, and one that wealthier residents should adopt, not all Jakartans are able to follow suit due to financial or other constraints.

“For many residents, the only option is to raise the floor level by backfilling, or, if they have the funds, to add a second floor so that at least their valuables will be safe from the flooding,” Prof Herlily told ST.

The new “rumah panggung” design aims to prevent flood waters from entering the house while also allowing rainwater to be absorbed back into the ground.

ST PHOTO: KARINA TEHUSIJARANA

Ms Kurniasari, 52, who goes by one name, is one such resident. She has lived in her house in the Warung Buncit area of South Jakarta since birth. Her neighbourhood is prone to flooding, and she has found that it has worsened over the years.

“It has gone from something that happens every five years, to something that happens every year, to something that happens almost every time there is heavy rain,” she told ST.

Ms Kurniasari finally decided to raise the floor around 10 years ago, after a frightening incident where she was almost electrocuted when flood waters entered the house.

“After that, I decided to get the floor raised by about 100cm,” she said. At the time, her house was among the highest in the neighbourhood, but over time, more and more of her neighbours have raised their houses too.

“So we’re all at about the same height now,” said Ms Kurniasari.

With flood levels rising every year, she acknowledged that turning her house into a stilt house was probably the best solution. But one major constraint is that she lives with her 85-year-old mother, who is no longer able to manage too many stairs.

“So I’ll leave that problem to the future generation, as I probably won’t be here any more,” she said with a laugh.

Prof Herlily said that while it was not feasible for the Jakarta administration to enforce or incentivise stilt houses, the city should set a good example by adapting its own buildings and plots to double as catchment areas.

While the Jakarta administration has begun integrating public parks with water infiltration areas, adapting its buildings has not been a priority so far, as the city has focused more on river widening and dredging. Officials from Jakarta’s Public Works and Spatial Planning Department did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Mr Aditya echoed the sentiment, saying: “Since Jakarta is a city of water, its buildings should also be water-friendly. If we see water as the enemy, when it rains, it’s like the enemy has arrived. We’re anxious, we can’t sleep and can’t focus on work because we’re always worried whether it will flood.”

“But if we see water as part of our life, we’ll welcome it, and we’ll even be happy when it comes,” he added.