Why North Korea may give up its nuclear crown jewel Yongbyon at Trump-Kim summit

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

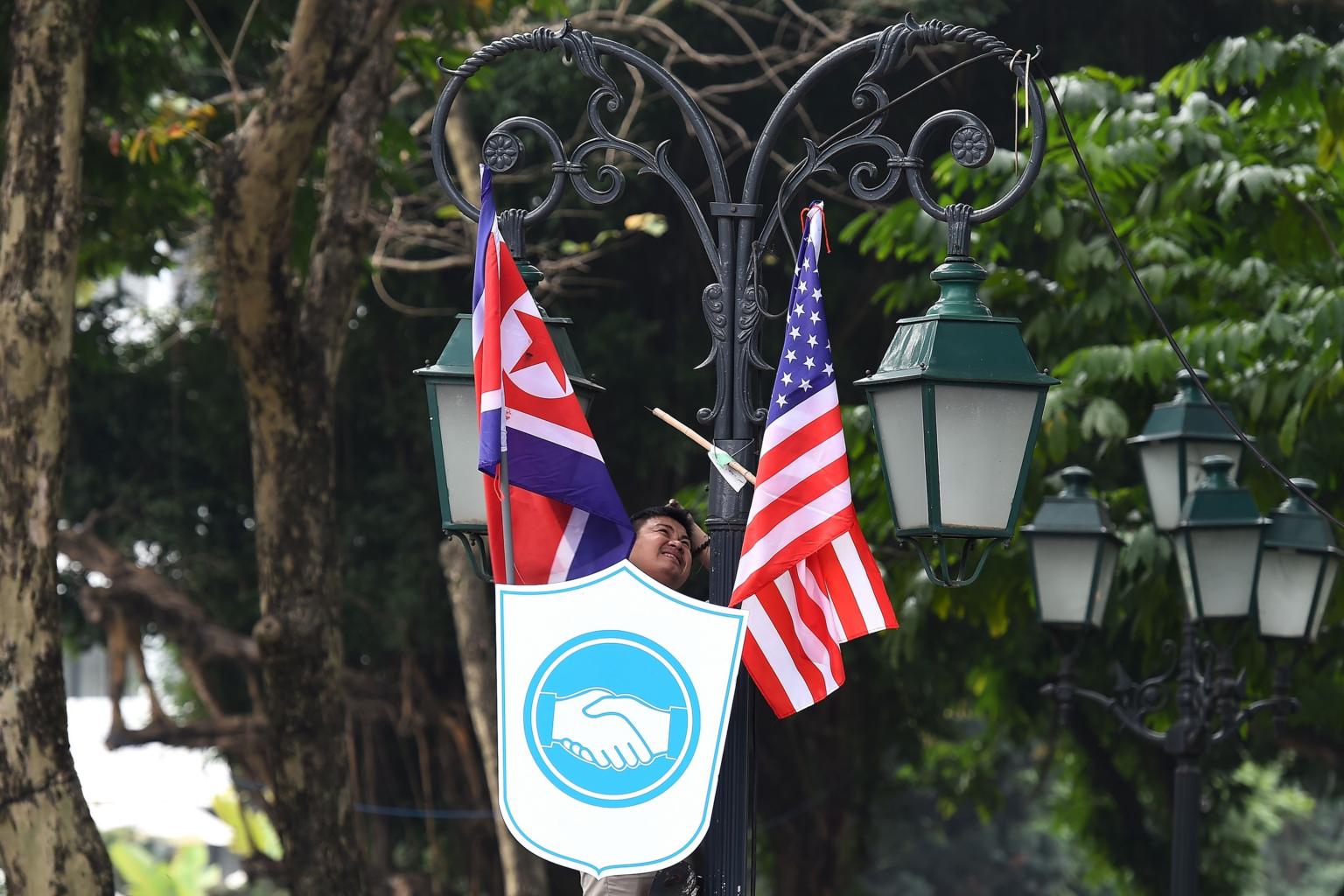

A worker puts up North Korean and US flags in preparation for the upcoming Trump-Kim summit in Hanoi, on Feb 19, 2019.

PHOTO: AFP

Follow topic:

SEOUL/TOKYO (BLOOMBERG) - For much of the past four decades, North Korea's nuclear ambitions have focused on a sprawling complex nestled in the mountains north of Pyongyang.

All of that could come to an end after United States President Donald Trump and leader Kim Jong Un meet next week.

The dismantlement of the Yongbyon Nuclear Scientific Research Centre has emerged in recent months as a potential outcome from a second summit between the leaders planned for Feb 27-28 in Vietnam.

Mr Moon Chung-in, a special adviser to South Korea's president, told Bloomberg last week that Mr Kim had agreed to close the plant and allow inspectors - possibly giving the US valuable insights into Mr Kim's weapons programmes.

A deal to shutter Yongbyon would represent Mr Trump's first tangible victory toward reducing Mr Kim's nuclear capacity since he granted an unprecedented meeting last June - even though North Korea has made similar promises before.

The move could potentially deprive Mr Kim of enough plutonium to make roughly one atomic bomb a year, and possibly other materials needed to make smaller, more powerful nuclear weapons.

Still, that would fall far short of the "final, fully verified denuclearisation" that Secretary of State Michael Pompeo and other Trump administration officials have demanded.

Even if he closes Yongbyon, arms control experts say Mr Kim probably has at least one other secret plant that can produce enough uranium to make as many as six nuclear bombs a year.

Mr Chun Yungwoo, a former South Korean nuclear envoy who helped broker one of the deals to shut Yongbyon, said the regime has shifted its focus to building better warheads and intercontinental ballistic missiles that could hit the US.

North Korea probably has enough fissile material to continue most of its nuclear weapons programme, even if it closed all its other fuel-production facilities, Mr Chun said.

"Ten years ago, that was our main concern," he said. "The relative value of Yongbyon and the enrichment plants outside of Yongbyon is now negligible."

Mr Trump told reporters at the White House on Tuesday that he was in "no rush whatsoever" to reach a deal with Mr Kim because he has a strong relationship with the North Korean leader and that sanctions against the country remained in place while the two sides talk.

Meanwhile, the US special representative for North Korea, Mr Stephen Biegun, was traveling to Hanoi to prepare for the summit, the State Department said.

Yongbyon, located about 100km north of the capital Pyongyang, carries symbolic value as the long-time crown jewel of North Korea's nuclear weapons programme. First constructed in 1979, its reactor has produced little electricity, but supplied the plutonium and research facilities needed for North Korea to test its first atomic bomb in 2006.

Mr Kim put Yongbyon back on the table in a meeting with South Korean President Moon Jae-in in September, when he expressed a willingness to accept the "permanent dismantlement" of the plant in exchange for "corresponding measures" by the US.

Mr Moon Chung-in, the president's adviser, said Mr Kim also agreed during that meeting to "accept verification" of its demolition.

Closing Yongbyon, as well as a lab that might produce tritium - a radioactive isotope of hydrogen that helps in miniaturising warheads - would be a success, according to Mr Siegfried Hecker, who was among a group of nuclear scientists who observed a uranium-enrichment operation at the facility during a 2010 inspection tour.

NUCLEAR BOMBS

"Shutting down and dismantling the Yongbyon nuclear complex is a big deal," said Mr Hecker, who has visited the site four times. "It will stop the production of plutonium and tritium. And it will greatly diminish the ability to make highly enriched uranium."

Still, inspecting the dozens of buildings at Yongbyon could take weeks and full dismantlement would drag on even longer. Disagreements might arise over how much of the complex is covered by any deal.

South Korea and other advocates of a gradual approach to talks with North Korea argue that Yongbyon's dismantlement would build trust and encourage more significant concessions by Mr Kim.

Mr Biegun, the US envoy, said last month that the North Korean leader has committed to the dismantlement of enrichment facilities "beyond Yongbyon" in conversations with Mr Pompeo and South Korean officials.

How much Trump administration can accomplish by next week remains uncertain. Mr Biegun told visiting South Korean lawmakers last week that it would be hard to resolve remaining disputes in advance and that talks were likely to stretch beyond the summit.

In exchange for dismantling Yongbyon, Mr Kim would probably demand relief from international sanctions - the US' main point of leverage in negotiations. The demolition would require delicate negotiations on where and when inspectors can roam, an area where similar talks collapsed a decade ago. The regime might divert nuclear materials to other facilities.

North Korea twice agreed to halt operations and let in nuclear inspectors in exchange for aid before Mr Kim took power, once in the mid-1990s and again in the mid-2000s. Both times, North Korea walked away and returned to military provocations after disagreements over how to implement the deal.

"We do want to make sure that the 'shutdown of Yongbyon' is as comprehensive as possible and as irreversible as possible," said Ms Melissa Hanham, a non-proliferation expert and director of the One Earth Future Foundation's Datayo Project. "We don't want to repeat the mistakes of the past."