Outcry for local election after departure of KL’s ‘first world-class mayor’

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

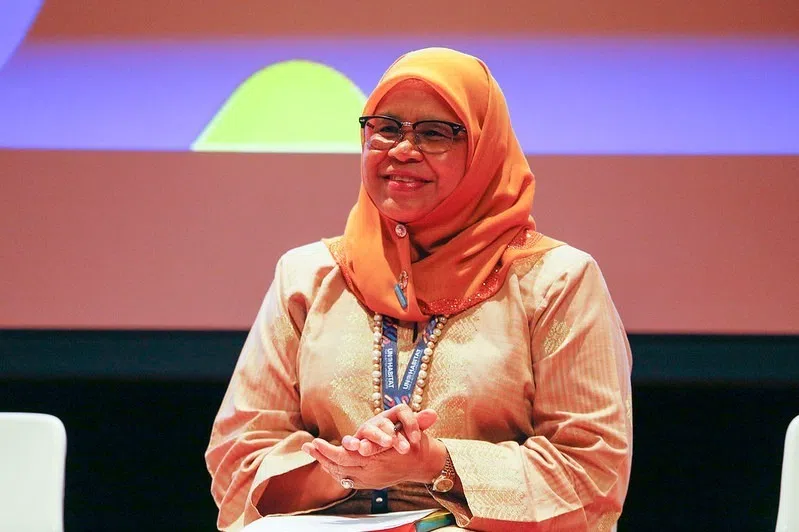

Datuk Seri Maimunah Mohd Sharif left Kuala Lumpur City Hall in November with little explanation.

PHOTO: UN-HABITAT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MAIMUNAH MOHD SHARIF/FACEBOOK

- KL's first woman mayor, Maimunah Mohd Sharif, left after 16 months, sparking calls for elected mayors due to lack of transparency.

- KL lacks local representation, with decisions made by the Federal Territories Ministry, favouring property developers over residents.

- Advocacy groups highlight inequalities, emphasising the need for resident involvement in urban planning for a liveable city.

AI generated

KUALA LUMPUR – The abrupt departure of Kuala Lumpur’s first woman mayor after just 16 months has reignited calls for the Malaysian capital’s two million residents to elect their own leader, rather than having one appointed by the federal government.

Datuk Seri Maimunah Mohd Sharif, a champion of inclusive urban planning, left Kuala Lumpur City Hall (DBKL) in November 2025 with little explanation – raising questions about the city’s direction, and highlighting the political vulnerability of appointed mayors who lack a popular mandate.

Documentary filmmaker Amirul Ruslan, who runs The KUL Things account on TikTok and Instagram covering the city, said it was very disappointing to lose someone of her calibre.

“KL lost its first world-class mayor, for what we keep saying is a world-class city,” said Mr Amirul, who also runs the Explaining Malaysia YouTube channel.

“The lack of transparency we saw with Maimunah’s transfer, with secretive press releases published in the middle of the night, really was a stark reminder of how not having our own elected mayor hurts the city in the long term.”

Madam Maimunah had a stellar career before her short stint at the DBKL; she was the first Asian woman to be appointed executive director of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

She has now been redeployed as the property adviser at Malaysia’s state-owned oil company Petronas, while Mr Fadlun Mak Ujud – a former president of Putrajaya Corporation that administers the federal administrative capital – was appointed to succeed her at DBKL.

Mr Amirul, who had engaged with Madam Maimunah as part of his city advocacy work, vouched for her commitment to reducing bureaucracy while maintaining rigorous oversight. He also said she wanted to meaningfully improve public transport with bus and cycle lanes, something not all previous mayors were concerned about.

“It’s sad that the abruptness of her contract termination means we’ll never see a progress report on the good work she was doing,” he added.

Under her stewardship, more than 90 per cent of public complaints were resolved and her focus on managing the city’s finances led to the first surplus in the city’s accounting in over a decade at RM27.6 million (S$8.7 million) in 2024, in contrast with deficits of RM75.3 million in 2023 and RM283 million in 2022.

The mayor’s departure caught the attention of KL’s Members of Parliament, the city’s only elected representatives. They have since taken it as an opportunity to call for the return of local government elections, arguing that the Malaysian capital has not had a mayor who meets the benchmark for developing a well-run and high-integrity city.

“We have seen ministers and mayors come and go, but none has yet met the standard needed to build a capital city that is efficient and has integrity,” said nine-term MP of Cheras Tan Kok Wai, at the Kuala Lumpur Democratic Action Party’s annual convention on Nov 16.

Setiawangsa MP Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, meanwhile, said Madam Maimunah’s sudden departure was “further proof” that there needs to be a change in how KL is governed.

“Today, the city’s residents do not have a say in how the city is run, with power in the hands of a sole mayor appointed by the federal government, traditionally from the civil service,” Mr Nik Nazmi said in a statement on Nov 14.

KL’s right to vote for its local government was scrubbed under the Federal Capital Act 1960, which provided the framework for direct federal rule of the city instead of an elected local council.

Residents’ representation dwindled further in 1974 when KL was carved out of Selangor and made a Federal Territory, stripping the capital of its state-level representation. This means that despite having a 2025 budget larger than Johor’s, at RM2.8 billion against RM2 billion, KL’s citizens have no say in who decides how money is spent or how their city is shaped.

Instead, all decisions are made by the Federal Territories Ministry, which is under the Prime Minister’s Department and is also in charge of overseeing the administration and development of Labuan and Putrajaya.

Mr Aziff Azuddin, research director at think-tank Iman Research, said the lack of representation has turned KL from being a city for its residents to one shaped by property developers.

“Kuala Lumpur hasn’t been a city for KLites for the longest time because although it has MPs, there are no local representatives and no councillor system that allows management at the local level,” Mr Aziff told The Straits Times.

His research found that KL is becoming a city for tourists, with residential developments in the past 15 years skewed towards projects designed for short-term stays, particularly Airbnb rentals, instead of dedicated residential homes.

Mr Aziff’s study found that 38 new properties around the city’s Golden Triangle shopping districts of Kuala Lumpur City Centre and Bukit Bintang are intended for short-term rentals, against 29 for dedicated residential homes.

These projects often command higher price-per-square-foot ratios despite having smaller unit sizes, and are increasingly built on commercial land. Frequently marketed for investment for Airbnb use, they boast facilities and skyline views, and some even have a dedicated lobby for short-term guests and support from building management to help guests check in and out.

“The rise of these buildings means that developers are actively reshaping the inner city to be dictated mostly by transient communities. You either have migrant enclaves, or a fluid tourist community,” Mr Aziff told ST.

Unable to elect their local government, frustrated KLites cannot use the ballot box to push back against urban planning policies that allow the proliferation of these short-stay, investment-driven projects that lead to the hollowing out of neighbourhoods.

KL, previously overshadowed by neighbouring Bangkok and Singapore, emerged as one of the world’s top 10 most visited cities in 2024, with 17.5 million international tourist arrivals. It was a sharp spike of 73 per cent from 2023, earning businesses in the city almost RM28 billion from shopping alone.

With the Visit Malaysia Year 2026 campaign, the country expects to attract 47 million international visitors nationwide throughout the year.

Meanwhile, Kerja Jalan, a KL-based advocacy group promoting walkability, said the absence of representation translates directly into everyday inequalities.

“Decisions about neighbourhoods, public spaces, mobility and city systems are usually top down, and because we cannot elect our mayor, what we see in the city is rarely a true reflection of what residents want,” said Ms Awatif Ghapar, the group’s co-founder.

She noted that outside of the tourist hubs, the basics of urban living such as well-connected walkways, safe pedestrian crossings and accessible paths are still unmet. “These are not just design flaws, because they actually reflect whose experiences are being prioritised and who is ignored.”

The group, which organises walking tours around neighbourhoods in and around Kuala Lumpur, explores beyond just accessibility but also the local history and heritage buildings, with their recent walk joined by local council members from Johor, Shah Alam and Miri.

For Ms Awatif, a liveable city is not about more skyscrapers but restoring the rights of the people.

“It is the right to participate, to feel belonging, to feel ownership over their surroundings, and to feel like this is the place that they want to live, instead of being forced to live in certain ways because of the design and decisions that have been made,” she said.

Sign up for our weekly

Asian Insider Malaysia Edition

newsletter to make sense of the big stories in Malaysia.