World scientists look elsewhere as US labs stagger under Trump cuts

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

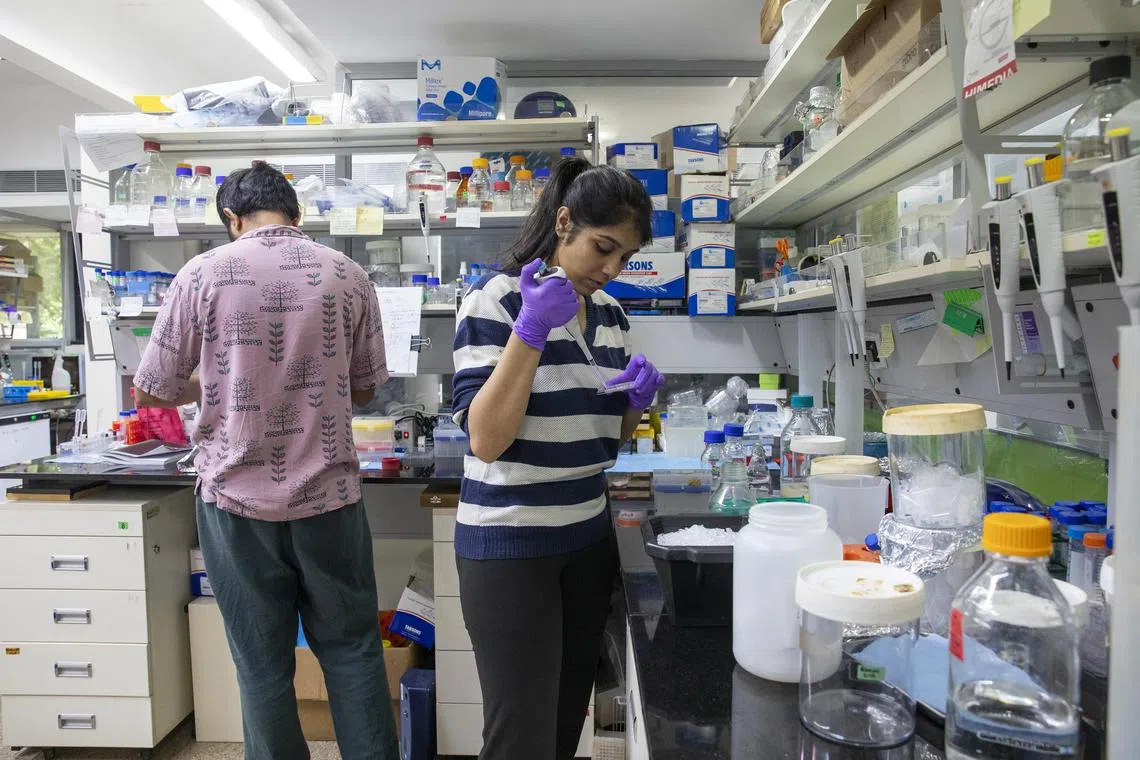

Professor Raj Ladher, of the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India, with PhD students on May 26.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

NEW YORK - For decades, Bangalore, India, has been an incubator for scientific talent, sending newly minted doctoral graduates around the world to do groundbreaking research. In an ordinary year, many aim their sights at labs in the United States.

“These are our students, and we want them to go and do something amazing,” said Professor Raj Ladher, of the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bangalore.

But this is not an ordinary year.

When Prof Ladher queried some 30 graduates in the city recently about their plans, only one had certain employment in the US.

For many of the others, the political turmoil in Washington has dried up job opportunities in what Prof Ladher calls “the best research ecosystem in the world.”

Some decided they would now rather take their skills elsewhere, including Austria, Japan and Australia, while others opted to stay in India.

As the Trump administration moves with abandon to deny visas, expel foreign students and slash spending on research, scientists in the US are becoming increasingly alarmed. The global supremacy that the US has long enjoyed in health, biology, the physical sciences and other fields, they warn, may be coming to an end.

“If things continue as they are, American science is ruined,” said physics and data science professor David W. Hogg of New York University, who works closely with astronomers and other experts around the world.

“If it becomes impossible to work with non-US scientists,” he said, “it would basically render the kinds of research that I do impossible.”

Research cuts and moves to curtail the presence of foreign students by the Trump administration have happened at a dizzying pace.

The administration has gone so far as moving to block any international students

At Johns Hopkins University, a bastion of scientific research, officials announced the layoffs of more than 2,000 people

An analysis by The New York Times found that the National Science Foundation, the world’s preeminent funding agency in the physical sciences, has been issuing financing for new grants at its slowest rate since at least 1990.

PhD students at the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

It is not merely a matter of the American scientific community losing power or prestige.

Biology and physics professor Dirk Brockmann, who is based in Germany, warned that there were much broader implications. The acceptance of risk and seemingly crazy leaps of inspiration woven into American attitudes, he said, help produce a research environment that nowhere else can quite match. The result has been decades of innovation, economic growth and military advances.

“There is something very deep in the culture that makes it very special,” said Prof Brockmann, who once taught at Northwestern University. “It’s almost like a magical ingredient.”

Scientists believe that some of the international talent that has long helped drive the US research engine may land elsewhere. Many foreign governments, from France to Australia, have also started openly courting American scientists.

But because the US has led the field for so long, there is deep concern that research globally will suffer.

“For many areas, the US is absolutely the crucial partner,” said Professor Wim Leemans of the University of Hamburg and director of the accelerator division at DESY, a research centre in Germany.

Prof Leemans, who is an American and Belgian citizen and spent 34 years in the US, said that in areas like medical research and climate monitoring, the rest of the world would be hard-pressed to compensate for the loss of American leadership.

There was a time when the US government embraced America’s role in the global scientific community.

In 1945, a presidential science adviser, Vannevar Bush, issued a landmark blueprint for post-World War II science in the US. “Science, the Endless Frontier,” it was called, and among its arguments was that the country would gain more by sharing information, including bringing in foreign scientists even if they might one day leave, than by trying to protect discoveries that would be made elsewhere anyway.

The blueprint helped drive the postwar scientific dominance of the US, said Mr Cole Donovan, an international technology adviser in the Biden White House.

“Much of US power and influence is derived from our science and technology supremacy,” he said.

Now the US is taking in the welcome mat.

Prof Brockmann, who studies complex systems at the Dresden University of Technology, was once planning to return to Northwestern to give a keynote presentation in June. It was to be part of a family trip to the US; his children once lived in Evanston, Illinois, where he taught at the university from 2008 to 2013.

He cancelled the talk after the Foreign Ministry issued new guidance on travel to the US

Mr Donovan said it was too early to tell whether Europe, say, or China could take over an international leadership role in science.

Prof Ladher, the Bangalore researcher, said that so far, Europe has been taking up some of the slack in hiring his graduates.

“Austria has become a huge destination for many of our students,” he said.

In Bangalore, one graduate student who is waiting to defend her doctoral thesis on cell signalling and cancer said it was widely believed in India that US labs were unlikely to hire many international students this year.

That has led many of her colleagues to look elsewhere, said the student, who asked not to be named because she still planned to apply for positions in the US and did not want to hurt her chances.

The American scientific community, she said, has long been revered abroad.

“It is sad to see that the hero is coming down from the pedestal,” she said. NYTIMES