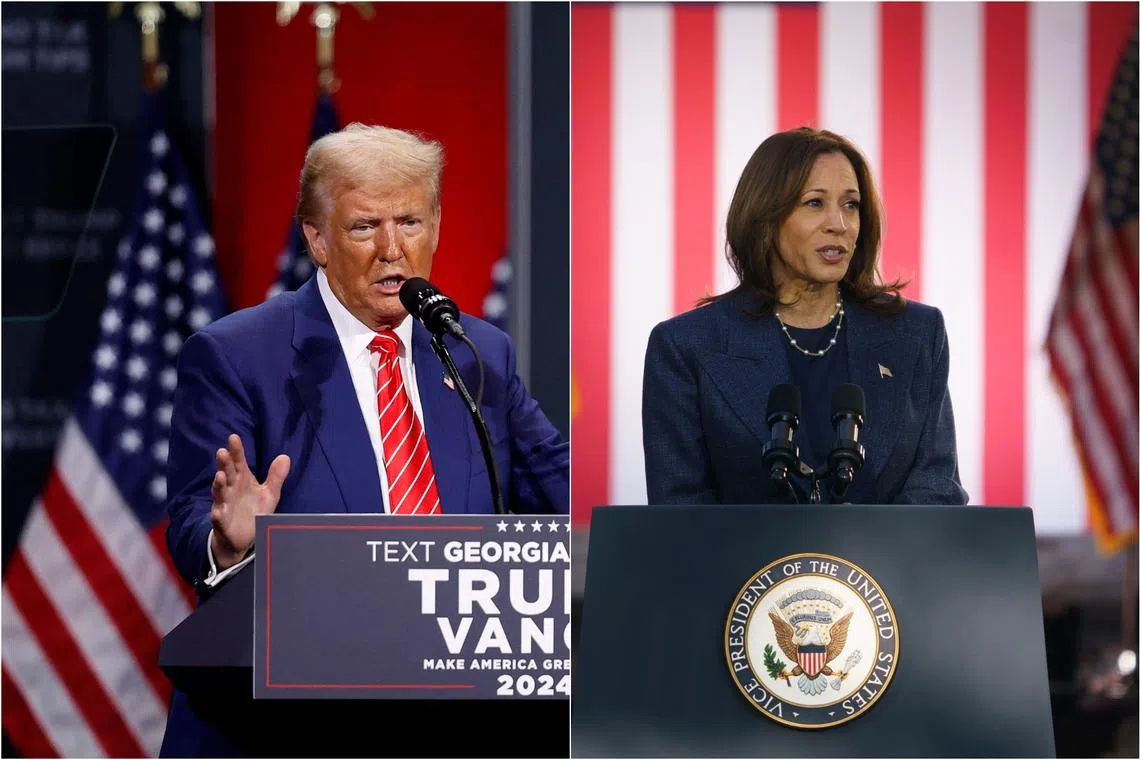

Why it may take days or longer to determine if Trump or Harris won the election

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

State laws and differing time zones can sometimes complicate reporting and race calls.

PHOTOS: EPA-EFE, AFP

NEW YORK - National elections in the US are a misnomer. In reality, there are 51 different presidential elections held the same day, one in each state and the District of Columbia.

Each one follows its own rules on where, when and how ballots are cast, which can impact when votes are counted and results are known. The way votes are tabulated can also produce so-called mirages, the appearance that a candidate has a lead somewhere which proves illusory.

Add in the peculiarities of the Electoral College and the potential for the Nov 5 presidential election

When do the polls close on Nov 5?

Each state sets its own polling times. The first polls are scheduled to close in Kentucky and Indiana at 6pm New York time (6am, Nov 6, Singapore time). Other states will follow throughout the night. The final polls are set to close in the westernmost precinct in the US, on the Aleutian island of Adak, Alaska, at 1am New York time on Nov 6.

If polling places are backed up, voters will be allowed to vote as long as they were in line as of closing time. And all of these times could be extended by court order under certain circumstances.

When do states start reporting results?

Most states can start reporting initial results within minutes after polls close. But state laws and differing time zones can sometimes complicate reporting and race calls.

In Kentucky and Indiana, for example, counties in the eastern time zone will start reporting vote counts even while voters in the central time zone are still casting ballots. Other states – including Alabama, Alaska, Oregon and South Dakota – typically hold off on reporting any results until all counties have voted. And in Arizona and Idaho, state laws require officials to wait an hour after polls have closed before reporting any results.

How long will it take to determine who’s won?

If the last presidential election in 2020 is any indication, it could take days. That year, the Associated Press – the unofficial and yet widely accepted real-time scorekeeper of US elections – did not declare President Joe Biden the winner until the Saturday after Tuesday voting. If this election is closer than that one – as many polls suggest it could be – it may take even longer.

In 2020, it was not clear who had won the presidency until it emerged that Mr Biden had secured the considerable Electoral College votes of Pennsylvania.

Mr Al Schmidt, the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, expects the 2024 count in the state to go faster. With the pandemic over, there will probably be fewer mail-in ballots, which take longer to process. Plus, Pennsylvania counties have invested in high-speed ballot sorters and scanners, and workers are more experienced with the process that was first implemented in 2020, he said.

But other states – notably Arizona, Georgia and North Carolina – have put in place laws that could slow the vote counting by creating additional steps for tabulating votes cast before Election Day.

Another wild card: In the run-up to the election, hurricanes that have hit the southeastern US could potentially disrupt voting there. Among the states impacted are the critical swing states Georgia and North Carolina. Swing states are those that have voted for both Democratic and Republican candidates in recent presidential elections and where the parties have similar levels of support.

It could take even longer to determine who controls Congress than the White House. The division between Republicans and Democrats in the two chambers is historically close, and the election could come down to late-arriving votes in a handful of seats.

Why does it take so long to determine a winner?

Some votes require additional processing time. These include:

Provisional ballots. A provisional ballot is cast by a voter when there’s some question about the validity of their vote on Election Day. It often requires more investigation about the voter’s registration status or precinct.

Mail-in ballots. These are usually sent in by voters inside two envelopes – with the inner one containing the voter’s signature, which needs to be verified. Some states allow mail-in ballots to be preprocessed and then counted on Election Day or earlier (though in that case, the count is kept secret until all eligible voters have had a chance to cast a ballot). Others prohibit election officials from even opening the envelopes until the polls close. In either case, officials also need to check that the voter hasn’t also cast a vote in person.

Some states require mail-in votes to be received by Election Day. Others allow votes to be counted as long as they are postmarked by the time the polls close, making it difficult to predict how many ballots are outstanding and when they will arrive.

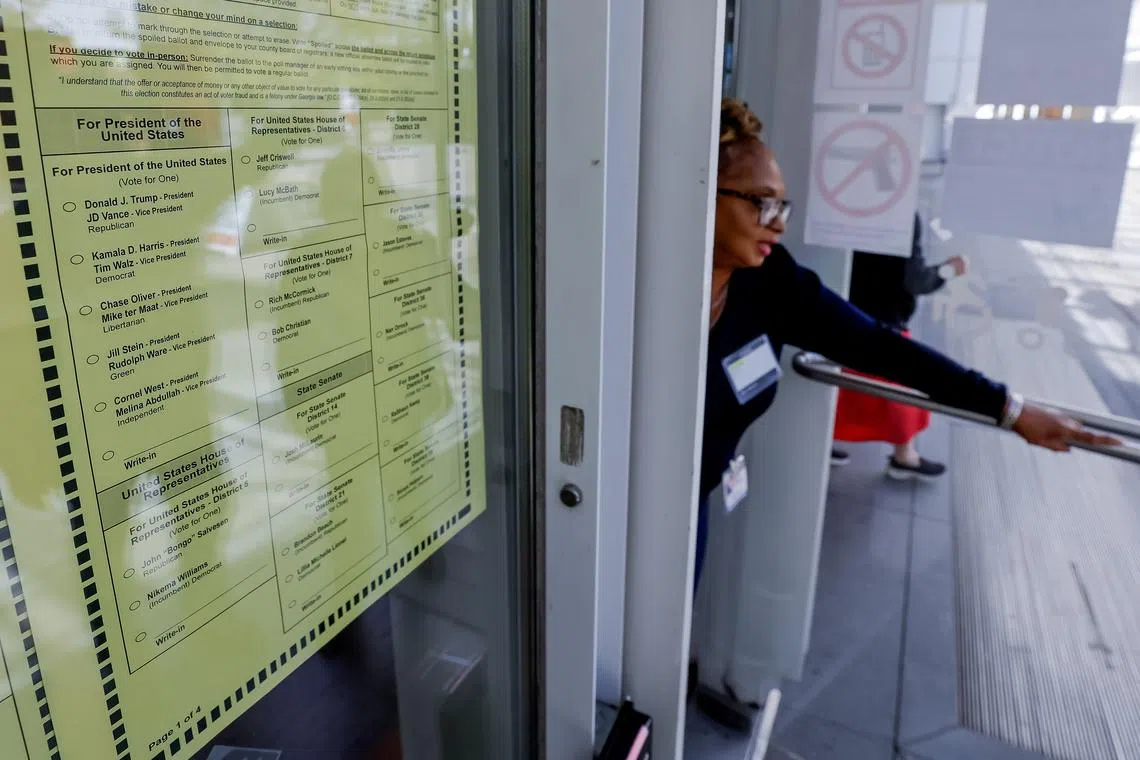

A poll worker opens the entry door to allow voters to cast their ballots during Advance Voting (Early Voting) in Georgia for the US presidential election on Oct 16.

PHOTO: EPA-EFE

US military personnel and American citizens living overseas are entitled to have their votes counted if they are postmarked by Election Day and received within 13 days under a 1986 law known as UOCAVA – the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act. That means the earliest any state can certify its results is Nov 19.

In a close election with high voter turnout, those provisional and absentee ballots can strain election counting systems. That’s what happened in 2020, when seven in ten voters cast a ballot before Election Day, either in person or by mail.

What can cause a ‘mirage’ in voting results?

It is called a mirage when one candidate jumps out to a quick lead based on an unrepresentative sample of the first votes counted. If it is the Republican candidate getting a deceptive early lead – which is often but not always the case – it’s called a “red mirage”. When results swing the other way in such a case, it’s called a “blue shift”.

There can be a number of causes for mirages. Votes are not counted in random order, and the sequence of counting can produce early results that are not representative of the state as a whole. Precincts closest to county election offices can get their ballots in first, electronic votes can be counted quicker than paper ballots, and smaller precincts report faster than bigger ones. Weather, poll worker fatigue, and other factors can also affect the pace of vote counting in some places and not others.

Then there are those mail-in votes, which tend to favor Democrats. The different state rules about how mail-in votes are processed can lead to mirages of different types.

Pennsylvania provided a stark example of a mirage in 2020. At midnight on election night, then-President Trump held a 13-point lead over Mr Biden in the state, with 43 per cent of the vote counted. But Mr Biden slowly eroded that lead as early and absentee votes that were mailed in were counted. The Associated Press finally called the state – and with it the presidency – for Mr Biden four days later.

This pattern led to some conspiracy theories in 2020, as Trump questioned the provenance of ballots that were counted late. Trump attributed them to “surprise ballot dumps”, but election officials and even some Trump campaign staffers had been warning for months that mirages were likely. And a Trump-appointed federal appeals judge found that his campaign never alleged – much less proved – that votes for Mr Biden were handled any differently than votes for Trump.

Who calls the winner?

Results are not official until they are certified by election officials, a process that can take as long as five weeks – or longer, if there’s a court challenge. But most people want to know the winner long before that – no one more so than the president-elect, who needs time to prepare a transition to power.

The Associated Press has called every presidential election since former President Zachary Taylor in 1848, and has since become the most widely accepted authority on who is winning which race.

The AP, a news cooperative of which Bloomberg News is a member, is able to do that by positioning 4,600 correspondents at boards of elections across the country. In past decades, those reporters would watch the ballots being counted and call in the results as they came in.

Nowadays, the AP collects data both from correspondents and from state and local election agency websites. Because that process is less labor-intensive, the AP has competitors such as Decision Desk HQ. A private company founded in 2012, it boasts of providing earlier race calls but has a shorter record of doing so accurately.

Collecting real-time returns is only part of the challenge. A team of experts at the AP and at each of the US television networks – known as “decision desks” – separately combine those returns with historic voting patterns and exit polls to call a winner. That’s why they’re able to call some races as soon as the polls close, even before a single vote is counted.

Calling the results in the closely contested swing states – which this year are considered to be Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – could take especially long.

Bloomberg News relies primarily on the Associated Press but will also “call” a state if two or more established TV networks, such as NBC, CBS, ABC, CNN or Fox, calls the race.

Of course, the Nov 5 election actually determines not who is president but which so-called electors get to cast a vote in the Electoral College. Those electors are scheduled to meet on Dec 17 in their state capitals to cast their votes for president and vice-president.

Even then, the race is not over. An elector has, on rare occasions, cast a vote for someone other than the candidate to whom the elector was pledged. If no candidate gets a majority of votes in the Electoral College, the House of Representatives would determine the presidency in a so-called Contingent Election. The presidential contest will not be final until Jan 6, when Congress is scheduled to meet to receive the electoral votes and certify the winner.

Could the race calls be wrong?

The Associated Press says its race calls are not projections or predictions. Rather, it says, it only calls races when it determines there’s no way the trailing candidate can win.

Still, bad data sometimes leads to errant calls. The AP has had to retract a small number of the thousands of race calls it makes on election night, for an accuracy rate of more than 99.9 per cent. Most retracted calls happen in low-profile races, but in an exception, the AP had to retract its call that Representative David Valadao of California had defeated Democratic challenger TJ Cox in 2018.

In 2020, Fox News and the AP called Arizona for Mr Biden early on the morning after Election Day, a call widely seen as premature but ultimately correct.

Four television networks called Florida for Al Gore over George W. Bush in 2000 before quickly backtracking. Mr Bush eventually won the state – and the election – after a weeks-long court battle ending in the US Supreme Court.

And in perhaps the most famous race-call blunder, early editions of the Chicago Tribune picked the wrong winner of the 1948 election, giving then-President Harry Truman an iconic photo op. BLOOMBERG