When did cancel culture become ‘consequence culture’?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

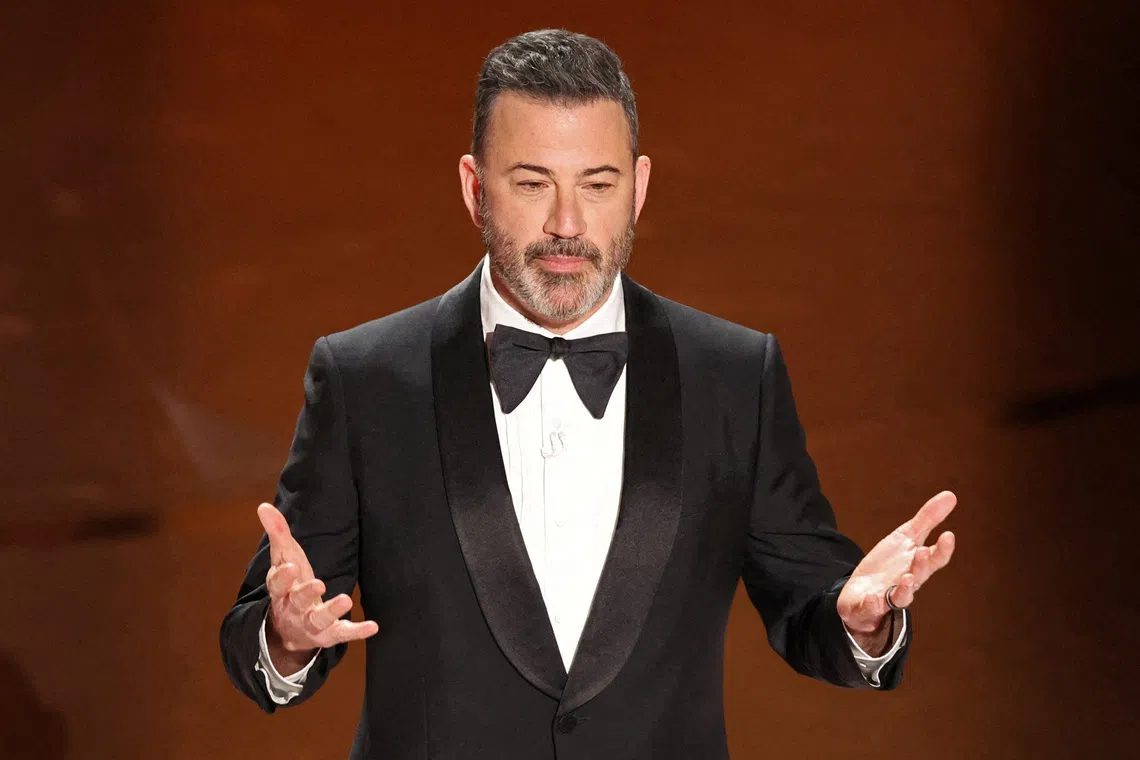

Some supporters of US talk-show host Jimmy Kimmel are accusing the right of embracing the same “cancel culture” it once maligned.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Joseph Bernstein

Follow topic:

Instead of cancel culture, call it consequence culture.

At least, that is what some Republican leaders and prominent conservatives are doing in the week since the assassination of political activist Charlie Kirk

On Sept 17, ABC suspended Jimmy Kimmel’s show over comments the late-night host made accusing “the Maga gang” of trying to portray as a leftist the man who has been charged with Mr Kirk’s murder.

The pressure campaign being carried out by Mr Kirk’s allies – and led by the White House, where Vice-President J.D. Vance has encouraged Americans to report to employers anyone “celebrating” Mr Kirk’s death – was known as “cancel culture” not long ago.

In the past several years, some conservatives weaponised that term to attack those on the political left for trying to professionally harm or socially ostracise those who made statements or took actions deemed unacceptable.

Now, some Kimmel supporters and others are accusing the right of embracing the same “cancel culture” it once maligned. In response, some Trump supporters are reframing it as “consequence culture”.

“When a person says something that a ton of people find offensive, rude, dumb in real time and then that person is punished for it, that is not cancel culture. That is consequences for your actions,” Mr Dave Portnoy, the founder of Barstool Sports, wrote on social platform X on Sept 17.

In an e-mail, Mr Portnoy declined to elaborate on his comments.

The term has been gaining traction in conservative media, in a headline in National Review (‘Consequence culture’ comes for the angry left) and posts on X from conservative activists like Ms Riley Gaines, who wrote on the night of Sept 17: “Cancel culture? No. Consequence culture.”

Although many pundits seem to have recently adopted the term, it is not new. And neither did conservatives invent it.

“Consequence culture” began floating around in the late 2010s, when social media campaigns called for the firings and ostracism of cultural figures for insensitive or offensive statements.

When “cancel culture” entered the popular lexicon to describe these campaigns, many on the right rallied against it as their cause celebre, citing the chilling of speech.

“The right made it their brand to talk about resisting being cancelled,” said Professor Meredith D. Clark, associate professor of race and political communication at the University of North Carolina’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media. “And I have to give it to them, they are masters of branding.”

In reaction, those attempting to punish offensive behaviour sought to distance themselves from what quickly became a loaded phrase.

“The term cancel culture is a bad faith fallacy,” actor Alex Winter of Bill And Ted’s Excellent Adventure wrote on Twitter in 2019, referring to men who lost their positions in the entertainment industry following accusations of sexual misconduct.

“There is only consequence culture,” he added. “It is long overdue, and most of the exposed predators have yet to face meaningful consequences.”

From there, the term trickled up to figures in the mainstream media.

In 2021, former Fox News host Lou Dobbs lost his show amid a defamation lawsuit that accused him of spreading conspiracies about a voting machine company in the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election.

“It is not cancel culture here,” Mr Brian Stelter, then the host of CNN’s Reliable Sources, said at the time. “It is consequence culture. What are the consequences for riling up people with reckless lies about a democracy that most Americans cherish?”

Also in 2021, The View host Sunny Hostin made a similar distinction in reference to efforts by Republican politicians to distance themselves from the Jan 6, 2021, insurrection.

“We hear so much from the right talking about cancel culture, cancel culture,” she said on air. “What they don’t want is a culture of accountability. They don’t want a consequence culture.”

And this summer, actor George Takei, a prominent liberal voice, shared a story on Facebook about the firing of a man who had described himself as a “fascist” during a viral YouTube debate. The caption read: “Freedom of speech does not mean freedom from consequences.”

Freedom of speech is enshrined in the First Amendment, and those cheering on firings over speech are often quick to point out that their enthusiasm is not in conflict with a prized American liberty.

One key difference between “consequence culture” from the left and the right, some have argued, has to do with who is enforcing those consequences. Most of the people fired for their posts about Mr Kirk’s murder have been sanctioned by private entities – which have every right to do so.

But Kimmel’s suspension appears to have resulted from pressure by the Federal Communications Commission, a government agency, and the First Amendment prohibits the government from restricting the speech rights of its citizens.

“That is not cancel culture at all,” said Stanford professor Adrian Daub, the author of The Cancel Culture Panic: How An American Obsession Went Global, referring to Kimmel. “By what definition of cancel culture is using the levers of state to get a guy fired from his media job ‘cancel culture’? We don’t need the fancy neologism... It is just an authoritarian crackdown.”

Whatever it is, Mr Kirk’s supporters have a term for it, and it is one they learnt from their political enemies. NYTIMES