As US TikTok users flock to Chinese app Xiaohongshu, interest in Mandarin rises

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The unexpected digital mass migration in the US has surprisingly sparked a viral interest in learning about Mandarin and Chinese culture.

PHOTO: AFP

Grace Ng

Follow topic:

NEW JERSEY – In a crowded high school cafeteria in New Jersey, Ms Ellie Lindal took a video of her shrivelled cheeseburger and posted it on Chinese-owned social media app Xiaohongshu, which Americans call RedNote.

She added a caption translated into Chinese: “This is my bleh school lunch, my Chinese comrades. Your dumplings and noodles look much better!”

Within minutes, comments and airbrushed photos of mouthwatering local cuisine poured in from Xiaohongshu users with IP addresses from cities like Beijing and Chongqing.

This cultural exchange among American and Chinese youth would have been quite unthinkable until just a week ago, when over 700,000 new users joined the app in just two days,

The influx came largely from American TikTok users seeking a new social media home as a ban on TikTok loomed in the US, which has about 170 million users of the app. TikTok said on Jan 17 that its service “will be forced to go dark on Jan 19” unless US President Joe Biden’s administration provides assurances to companies like Apple and Google that they will not face enforcement actions when the ban takes effect.

TikTok’s statement followed a decision by the Supreme Court on Jan 17 to uphold a law banning the platform in the US on national security grounds if its Chinese parent company ByteDance does not sell it. TikTok CEO Chew Shou Zi said on Jan 17 that he wants to thank US President-elect Donald Trump

US-China tensions, which have spiked amid thorny issues from trade disputes to national security concerns over technology access and allegations of Chinese spying, have precipitated a decade-long decline in bilateral people-to-people exchanges.

But the unexpected digital mass migration has surprisingly sparked a viral interest in learning about Mandarin and Chinese culture. Some analysts believe this offers a remarkable opportunity to stop a multi-year decline in Chinese language programmes and cross-cultural exchanges – or even reverse it.

Behind the bamboo curtain

The masses of new Xiaohongshu users come bearing hashtags like #tiktokrefugees and an overabundance of pet videos – dubbed a “cat tax”, or a digital cross-border tribute of sorts, paid to their Chinese hosts on the app.

And they appear to be achieving a diplomatic goal that US Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns had set out in 2023.

As China emerged from Covid-19 pandemic shutdowns that had caused American student numbers in the country to plummet to just 700 from 15,000 a decade ago, he had appealed to young Americans to learn the Chinese language.

“We need young Americans to have an experience of China,” he said.

This past week, US TikTok refugees immersed themselves in a digital experience of China, as Xiaohongshu users from both countries swopped information about their lifestyles, culture, cat memes and even homework.

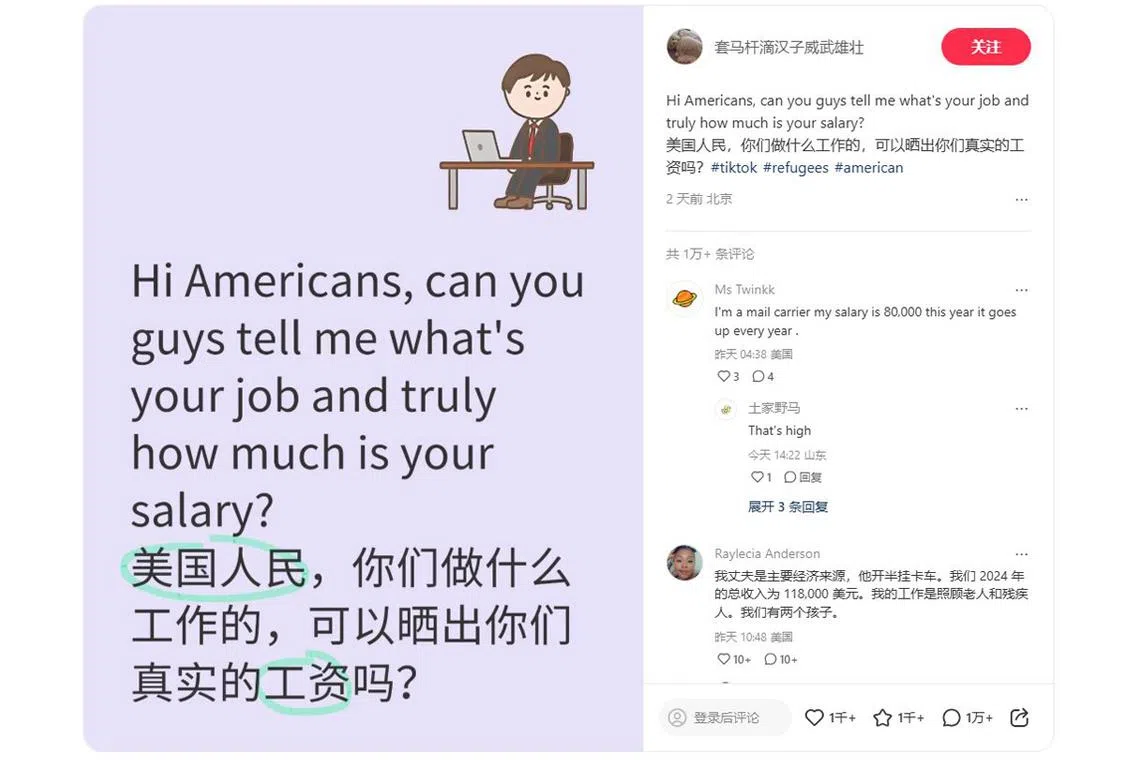

In a display of newfound trust, these denizens even bared all about their salaries and living expenses – personal finance topics that are typically inappropriate for small talk among American acquaintances, but blatantly discussed at Chinese dinner tables.

The topic “American and Chinese netizens spent the night reconciling financial accounts” topped the charts on China’s top microblogging platform Weibo, drawing some 160 million views so far – a testament to the unprecedented altitude of this mutual understanding.

A simple post by new Xiaohongshu user Maliha, a 30-year-old content creator in New York, asking “How much is university tuition in China?” attracted thousands of comments, and even became the Weibo masthead for this trending topic.

A simple post by new Xiaohongshu user Maliha asking “How much is university tuition in China?” attracted thousands of comments.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM XIAOHONGSHU

In a display of newfound trust, denizens bared all about their salaries and living expenses.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM XIAOHONGSHU

Need to experience China first-hand

Clutching tissues, 21-year-old hairstylist Amber Cook told her Xiaohongshu followers in a Jan 16 video that she had “finally found out the truth about China after being on RedNote for one day”.

“You guys have universal healthcare and amazing cars for very low prices. We’re the ones in a third-world country,” she sobbed. “The US media is lying about how bad China is.”

Hundreds of videos by TikTok and Xiaohongshu users bemoaning similar sentiments have spawned in recent days. Beijing-based global affairs commentator Jun Wuji reposted six of these videos on Weibo for his three million followers.

After one night of “reconciling financial accounts”, or dui zhang as the Chinese call it, “American netizens’ heavens have collapsed; it’s China that is truly the best country on earth”, he declared.

This rush by social media users on both sides to draw their own – often shaky – conclusions about what the real picture is in the two incredibly complex global powers adds urgency to the need to restore on-the-ground exchanges and foster more informed understanding, experts say.

While the digital interactions are a positive factor for reviving intercultural understanding, they cannot replace on-the-ground interactions, pointed out Professor Elizabeth Tuleja of the University of Pennsylvania’s Fels Institute of Government.

“We need to experience life in China first-hand and all that it has to offer,” said Prof Tuleja, a Fulbright China scholar and one of 60 foreign experts who received the Friendship Award in Beijing in January 2020.

“It was an honour to bring my skills and knowledge to Sichuan University (from 2017 to 2020) while learning so much from my Chinese students – and our collective insights were far richer because they were derived from in-person interactions.”

Professor Elizabeth Tuleja was one of 60 foreign experts who received the Friendship Award in Beijing in January 2020.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ELIZABETH TULEJA

Beware the beauty filters

Like other super-apps such as TikTok and WeChat, Xiaohongshu integrates functions such as short-form video, live streaming and e-commerce, while refining its algorithms to feed users’ interests with highly engaging content.

Before the influx of TikTok refugees, young urban females made up 70 per cent of the user base of Xiaohongshu. The app is a unicorn start-up headquartered in Shanghai, with major investors such as Alibaba Group Holding and Singapore’s Temasek.

Social media consultant Victoria Chenko said that the US ban on TikTok

“I think one reason why TikTok refugees have felt such positive, welcoming vibes on Xiaohongshu is that it has a tasteful, demure, positive user environment,” she observed. “What you see about Chinese users’ lives clearly has beauty filters, but I love seeing this stuff, and the content recommendation algorithm knows me too well. If you don’t have independent judgment, it’s easy to believe the doom scroll hype is the authentic truth.”

The irony of American netizens flocking to a Chinese-owned app instead of American platforms like Facebook or X has not been lost on US mainstream media.

Calling TikTok’s algorithm “social media perfection”, USA Today’s deputy Opinion director Louie Villabos wrote in a Jan 14 article: “Ban TikTok if you must, America. You’re just going to force a bunch of us to learn Mandarin.”

When Mandarin was not trendy

It is too early to tell if the enthusiasm for the Chinese language is sustainable or could fizzle out with the cat memes.

But at the very least, it spells hope for a revival in Chinese language course enrolment in the US, which dropped 21 per cent from 2016 to 2020, according to the Modern Language Association.

This has contributed to recent difficulties among some US school districts in sustaining their Chinese programmes.

In Montville, a township in New Jersey state, where one in 10 residents identifies as Chinese-American, the board of education announced in November 2024 that it planned to phase out its Chinese language programme, citing low enrolment. The programme’s class sizes were the smallest compared with the German, French and Spanish programmes.

Ms Sofia Matari, an 18-year-old freshman at New York University (NYU), had studied Mandarin in her Montville high school. She decided to launch a petition on change.org to appeal against the board’s decision.

“Cutting the only non-Western world language option will hinder students’ ability to engage with different perspectives (and) diminish their preparedness for a multicultural workforce,” she wrote.

Ms Sofia Matari launched a petition to appeal against the decision to phase out the Chinese language programme in Montville schools.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF SOFIA MATARI

Elsewhere, at least four school districts in states from California to Utah shared Montville’s dilemma about allocating limited resources to Chinese language programmes, based on change.org petitions and local news reports in 2024.

At a higher academic level, five college Chinese Flagship Programmes under the US Department of Defence were cut due to “congressional change in funding” in December 2024.

Meanwhile, a Bill to restore the prestigious Fulbright China programme, halted by the Trump administration in 2020, is still in limbo.

Economic impetus – or the lack thereof

While geopolitical tensions have undermined exchange programmes, declining US business and career prospects in China are arguably the key reason why Americans at large have become less motivated to learn Chinese compared with the 2010s.

When then President Barack Obama launched a 100,000-strong initiative in 2009 to boost the number of US students studying in China, the American public was mesmerised by China’s meteoric economic rise.

Children and CEOs alike flocked to learn this much-touted business language of the future, from Trump’s granddaughter to Meta’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who flaunted his fluent Mandarin during a 2015 Tsinghua University Q&A session.

That year, China surpassed the US as the largest economy – deemed a milestone.

Fast forward to 2024, the US economy is back at No. 1, ahead of China. And their gap in gross domestic product has widened to about US$10 trillion (S$13.7 trillion) – an interesting fact that Xiaohongshu fanatics like high-schooler Ellie noticed. “I thought China is better than us economically? I guess I should research more,” she said.

Meanwhile, China’s share of US imports has halved from a peak of 22 per cent in 2018 to 11.5 per cent in June 2024. So “foreign companies have been divesting at a faster rate” from China, noted JP Morgan Asset Management global market strategist Marina Valentini.

New reasons to learn Mandarin

While US expatriate and student numbers declined in China, there are still 300,000 or more Chinese students coming to the US each year. They join an increasingly vocal Chinese-American community that actively promotes their language and culture.

In Montville, for example, this group rallied support – even meeting with the town’s mayor – to retain the school district’s Chinese language programme, said Ms Ying Chen, who represented the parents in discussions with the Montville board of education.

“During the Covid-19 pandemic, there had been some anti-Chinese sentiment. Now, we need to rebuild bridges and respect for the Chinese community here. The Mandarin programme’s importance really lies in helping the younger generation of Americans understand and appreciate Chinese people and culture,” said Ms Chen.

These grassroots efforts are now getting a vocal online boost from American youth like Ms Matari, whose petition garnered 1,165 signatures. In mid-December, the board of education reversed its decision.

Asked if she will continue to study the language, she responded: “Yes, I’m hoping to visit China and participate in NYU’s exchange programme in Shanghai.”

“I think young people still recognise China as a major economic power. So there will still be significant opportunities for us to go to China to visit, work and join cultural exchanges,” she added.

Ms Sofia Matari (centre) performing at a Chinese New Year event at her Montville high school in 2024.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF SOFIA MATARI

These are the kinds of intercultural bonding that Prof Tuleja expects will make a comeback.

During a late December trip to China, she reunited with friends and former colleagues in Chengdu, capital of south-western Sichuan province, after five years.

“I was delighted that we picked up where we left off – that warmth and desire for cross-cultural understanding and friendship was as important as ever,” she said.

Since November 2023, when President Xi Jinping announced an initiative to invite 50,000 Americans to China over the next five years,

“With their first-hand experience, they have broken out of the echo chamber and shaken off misconceptions.”

Bridges or walled gardens

It remains to be seen whether Xiaohongshu will serve as a refuge for TikTok users to freely interact and reconcile differing accounts.

Chinese cyber regulators have reportedly ordered the company to “ensure China-based users can’t see posts from US users”, according to news outlet The Information.

“If regulators wanted to be clever, perhaps they could create a walled garden within Xiaohongshu where the foreigners can gather and post,” observed China expert Bill Bishop in his Sinocism newsletter.

“On the Chinese side, only ‘politically reliable’ users are allowed (in the walled garden), so the foreigners will think they’re having an authentic Chinese internet experience and learning about real life in China, but in fact, it would just be another managed people-to-people engagement.”

For now, as TikTok refugees continue their quest to further bilateral understanding on Xiaohongshu, the message to the broader US public is clear: Learning Mandarin is trending again.

Correction note: This story has been edited to give the correct number of Chinese students going to the US each year. We are sorry for the error.

Grace Ng, a former China correspondent for ST, is now based in the US as a business writer.