Pariah, felon, president-elect: How Trump fought his way back to power

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Donald Trump has been elected as the 47th US president against seemingly insurmountable odds.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Follow topic:

WASHINGTON – By late January 2021, just days into Donald Trump’s unhappy new life as a former president, his world had shrunk to a size he could not abide.

Self-exiled in Florida as a twice-impeached semi-pariah, he golfed and glowered, boiling over his 2020 defeat and still refusing to acknowledge its legitimacy.

His social media bullhorns had been silenced after Jan 6, with Twitter citing “the risk of further incitement of violence”. His circle had dwindled to a smattering of junior aides, straining to keep him on the fairways and away from the television.

“Get the pool,” Trump instructed at one point, referring to the hive of reporters who had trailed him daily as president. “I want to make a statement.” He was told that he did not have one any more.

By late February, Trump had waited long enough. In his first public appearance as a newly private citizen, he accepted an invitation to Orlando for a conference of right-wing activists.

“Do you miss me yet?” he asked, his arms splayed wide, as if waiting to be hugged.

It had been five weeks. Outside of that room, most Americans did not seem to miss him much at all.

Now, less than four years later, Trump’s arc back to power is complete – an extraordinary reversal carried off by a man who never especially changed, never accepted the reality of his 2020 loss, never stopped understanding the core of his own rampaging appeal, never doubted that he could bulldoze anyone in his way.

Yet, if Trump’s nine-lives life can feel divinely fated to his allies – transcending scandal, felony convictions, two attempts to assassinate him – what becomes clear in a close accounting of his trajectory since 2021 is that none of this was inevitable.

His path back to Washington was the product of foresight and chance, brazen calculation and his intuitive political skills amid almost unfathomable campaign volatility.

As much as anything, it required figures at every rung of American civic and political life making choices that helped deliver him to this point.

Republican senators acquitted him after the Jan 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol, even as some seemed to hope that he would be sidelined.

The authorities pursued him and brought four criminal cases against him, one of which led to his conviction on 34 felony counts, but their actions only deepened his base’s attachment to its leader. Donors, conservative-media titans and social media executives determined, eventually, that opposing Trump was unsustainable.

The Democrats initially stuck by an unpopular, visibly ageing incumbent.

And the voters, appraising it all, saw it fit to rehire Trump.

Political exile? Not for long

Several Republican lawmakers were unequivocal: Whatever he might try next, Trump was finished.

Fifty-seven senators found him guilty of “incitement of insurrection”

“I just don’t see how Donald Trump will be re-elected to the presidency again,” Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, one of seven Republicans who voted to convict, said at the time.

Trump was locked out of social media platforms, an afterthought for mainstream outlets, happily ignored by Democrats.

But the truth is that he was never as diminished as it appeared – or as his opponents hoped.

Many senior Republicans – especially Mr Mitch McConnell, the Senate minority leader who railed against Trump but voted to acquit him – were less than thrilled when Trump made it clear that he planned to play a major role in the 2022 midterm elections.

Ambitious contenders made beelines for his Mar-a-Lago estate to flatter him, play golf with him and beg for his endorsement, which was still the party’s most valuable commodity.

A top priority for Trump: ousting the House Republicans who voted to impeach him.

“Two down, eight to go!” he gloated in a statement when two of them announced their retirements from a changed party. While some of his candidates won, including Mr J.D. Vance, whom he endorsed for the Senate in Ohio, others fared disastrously.

Still, Trump was plainly the party’s most powerful voice.

It helped that the events of Jan 6

It helped even more, in August 2022, when federal authorities searched Mar-a-Lago for sensitive documents that prosecutors later charged Trump with keeping unlawfully.

Many Republican voters and activists were galvanised by the confrontation. Would-be primary rivals like Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida saw few options but to defend Trump, re-establishing the former president as his party’s unquestioned alpha.

Eager by then to announce his campaign, Trump had his criminal defence in mind: He believed, according to friends, that a formal White House bid would buoy his claims that any investigation was a political hit job.

And the Democrats’ better-than-expected performance in the midterms seemed to commit them to a dangerous bet: With a drubbing, President Joe Biden might have been pressured to step aside, as many voters hoped he would at his advanced age. Now, he was all in.

Trump wanted his rematch, and saw no one capable of stopping him.

Indictments, and endorsements, pile up

As a candidate again, Trump paid close attention to the language that lawmakers issued about his run.

Only full-throated endorsements (“the ‘E’ word,” he called them) were acceptable, he told associates. Rote expressions of support (“the ‘S’ word”) were insufficient.

But to many elected Republicans, Trump still looked vulnerable.

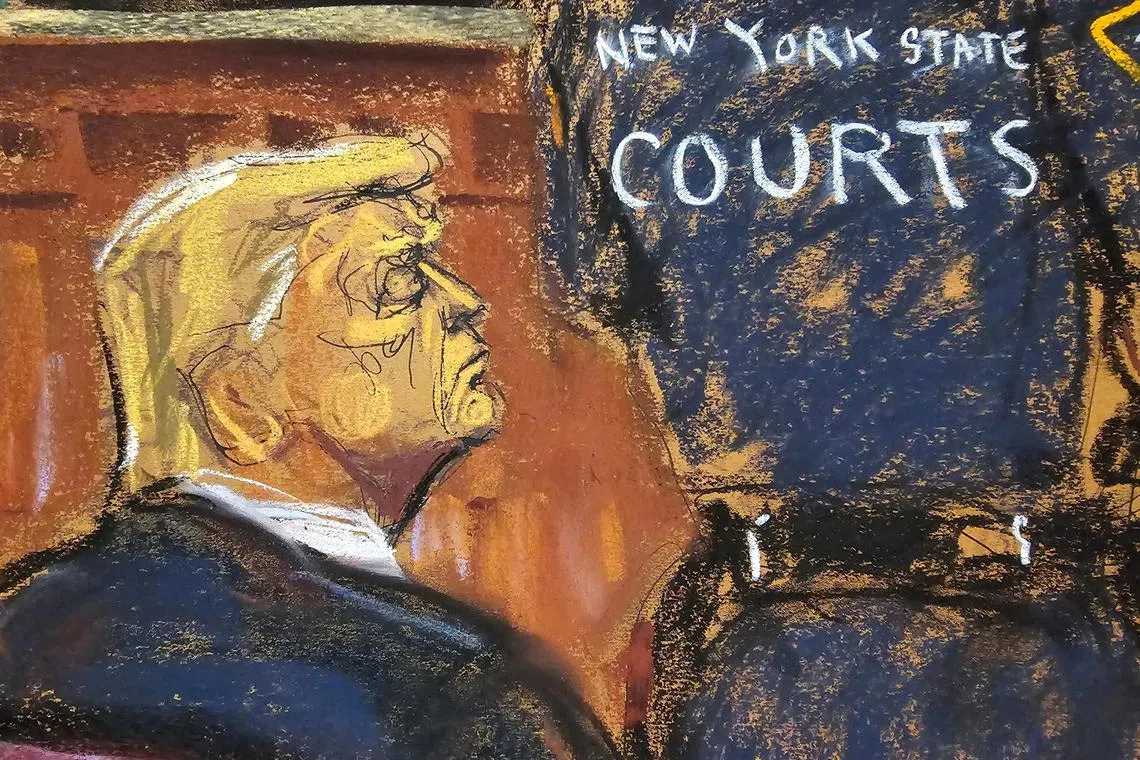

A courtroom sketch showing Donald Trump on May 30, 2024, as the verdict was read in his criminal trial on charges that he falsified business records to conceal money paid to silence porn star Stormy Daniels in 2016.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Donors were sidling up to his opponents. Key organs of conservative media were effectively shunning him: Fox News, which in 2023 reached a US$787.5 million (S$1 billion) settlement after airing baseless claims about the 2020 election, was refraining from interviewing him, and giving kinder coverage to some of his competitors

Legally, his team deployed a blizzard of delay tactics intended to push his trials beyond the 2024 election. Politically, Trump wanted to keep the charges against him front and centre, a spectacularly risky approach.

Some senior advisers raised concerns on uncomplicated grounds: Being charged with crimes is rarely professionally advantageous.

But Trump’s instincts were not just to lean into the charges but to organise his entire campaign around them.

As president, he had trained Republicans to come to his knee-jerk defence amid the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s probe into his 2016 campaign’s ties to Russia.

By the time Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg brought hush-money charges against him in 2023, the campaign hardly needed to send out talking points about the case being a “witch hunt”. The entire right-wing universe already knew what to say.

Suddenly, Trump was all over Fox again, hailed now as a martyr. His criminal arraignments became media spectacles. His aides back-channelled with network producers to turn his motorcade rides from airport to courthouse into live television events, evoking the O.J. Simpson Bronco chase.

His fund-raising and poll numbers spiked.

Most important to advisers, Trump’s main rivals for the nomination, Mr DeSantis and Mrs Nikki Haley, found themselves sidelined and compelled, awkwardly, to defend him. Trump did not even deign to debate them.

He won the nomination, easily, and set about painting Mr Biden as a doddering fool. Trump’s team agreed to an early debate, scheduled for June. It would exceed their wildest expectations.

A summer of unimaginable upheavals

Trump walked onstage in Butler, Pennsylvania, on July 13 as a solid polling leader against a hobbled incumbent.

He walked off, bloodied and fist-raising, as nothing less than a figure of destiny to many supporters.

“I’m not supposed to be here tonight,” he said of the assassination attempt

“Yes, you are!” the room chanted back.

Inside the arena, his victory could feel almost preordained. And Mr Biden was flailing, at war with his own party as he refused to abandon his bid.

Things changed quickly.

When Vice-President Kamala Harris suddenly became his opponent

Instead, Trump could not resist openly questioning her black identity. He aired groundless conspiracies from the online right about Haitian immigrants eating pets in Ohio. The more he campaigned, the more he reminded some voters of his unruly presidency, which the haze of time and Covid-19 had obscured.

But even as Trump made what seemed like major unforced errors, his pollster, Mr Tony Fabrizio, saw improvements in his internal surveys. After a low point in late August, when Ms Harris overtook him in several battleground states, Trump regained his footing.

He redoubled his pre-Harris strategy.

He mostly avoided the mainstream media, with the exception of Fox News. He recorded interviews with podcasters who have large audiences of exactly the kind of people the Trump campaign had identified as its most fertile targets: young men who are pessimistic about the country, bro-ish in outlook and often disinclined to vote. (Their support was essential as Trump seemed to have lost ground among women after appointing three of the Supreme Court justices who overturned Roe v Wade.)

At his rallies he was often incoherent, holding forth on Hannibal Lecter’s fictional brutality or Arnold Palmer’s genitalia, but rarely boring to his most zealous supporters, who continued to thrill at his merger of politics and entertainment.

He flashed some hustle on the campaign trail: the man with the golden tower serving fries at McDonald’s.

Trump also had the help of the world’s richest man.

In a manner unparalleled in modern history, Mr Elon Musk deployed his time, energy and vast resources to the goal of getting Trump elected.

After he bought Twitter (which he renamed X), he not only welcomed Trump back to the platform but ultimately turned it into a pro-Trump machine. He heavily funded a super political action committee to support a get-out-the-vote initiative.

And he joined Trump at rallies back in Butler and at Madison Square Garden, where the candidate mocked those alarmed by the increasingly authoritarian echoes in his language.

“When I say ‘the enemy from within’,” Trump taunted, “the other side goes crazy.”

After the shooting in Pennsylvania, some close to Trump had insisted he was a changed man, eager to unify.

If anything, in the months that followed, he seemed to become even less inhibited

Modulation would never come; it never had to, as Trump had wagered all along.

He is still promising retribution against his enemies and a campaign of mass deportation.

He is still adamant that he has never lost an election and never could.

He still knows what his followers see in him – the fury, the fight, the balm of “us” in an us-versus-them world.

He is who he is: the president-elect. NYTIMES