Commentary

Meet the quiet, brooding New York

New Singapore-style US$9 congestion toll eases the city’s torrid pace

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

A subdued looking midtown Manhattan with fewer cars on Fifth Avenue after the city’s congestion pricing programme kicked in.

ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

NEW YORK – The roads are not bursting at the seams and the city’s relentless pace seems to have eased.

With the new US$9 (S$12) congestion toll, driving into Manhattan now is a bit like watching a film in the silent era; it feels like something is missing.

For one thing, you actually get to see the road stretching ahead while driving through the city. Not the rear lights of the car ahead of you, inches away. Not its number plate or the drooling dog looking out the window with ruminating eyes.

Just the clear sight of the tarred road.

It’s not a pretty sight, admittedly, on this freezing, grey Thursday afternoon.

Just a narrow, uneven ribbon of a road, a pothole here, a patched-over pothole there. Street sides are backed up with little mounds of dirty snow. Trees are bare, dried-up yellow weeds stir with the passing breeze, and a garbage bag carelessly crosses the road.

But it is difficult to miss the purport of the moment. The frenzy is missing, the street is visible! Pitted and pockmarked in places, the thin traffic reveals the face of the new New York.

After overcoming five decades of hesitation

Drivers in the New York metro area lost 102 hours sitting in traffic jams in 2024, according to transportation analytics firm INRIX’s Global Traffic Scorecard. It takes 31 minutes on average to drive 10km in the city centre, according to another estimate.

At midnight on Jan 5, while its residents were presumably dreaming of a smoother ride, city officials unveiled plaques that announced that the southern tip of Manhattan – south of the 60th Street – would henceforth be the “congestion relief zone”.

Let Londoners call their toll the “congestion charge”. Let Stockholm refer to it as “congestion tax”. Let Singapore stick with “Electronic Road Pricing” or ERP.

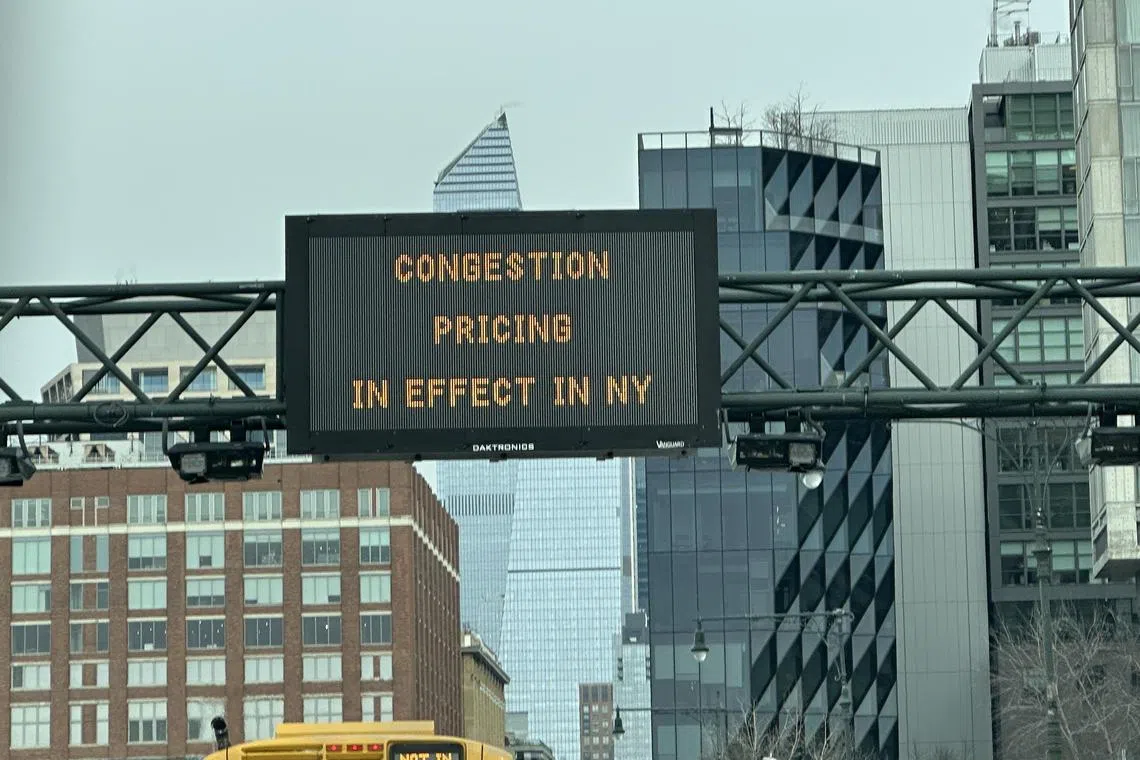

A sign in New York’s Meatpacking District announcing that the city’s congestion pricing programme is in effect, charging drivers who enter Manhattan’s Central Business District below the 60th Street.

ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

New York must live up to its reputation as the mecca of advertising hype. Public officials hope the toll goes down easier when they can call attention to the relief it promises with every mention.

In the congestion relief zone, a driver can now make the next green light and the next one and the next one – because the passage is not clogged with a line of drivers dutifully engaging their clutches in a stop-and-start slow dance through the streets while itching to check what the Dow is doing to their portfolios.

The traffic that was like the heaving sea just a week, year, and decade ago, is now an uncertain rivulet. Of course, tarry too long and you will get honked at; this is still the native land of the impatient.

The relief across zones is not equal, however. Travelling from Times Square towards Broadway during the lunch hour was the usual battle of nerves.

At one point, a police car behind me exhibited irritation by flashing its lights. But where could I move, stuck behind a car which was behind a car that was awkwardly wedged between two lanes?

From Broadway to the Empire State Building, passing through Seventh Avenue, I thought I saw Batman from the corner of my eye, his cape streaming in the wind. I turned my head to make sure: It was a one-legged man wearing a black jacket and a red Maga (Make America Great Again) cap, perhaps a war veteran, in a wheelchair. Expertly weaving against the traffic, he whooshed by in a few seconds while I stayed rooted to the spot in my vehicle.

Passing through Fifth Avenue, the traffic thinned again and I remembered snatches of President-elect Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign rhetoric – that he could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and would still not lose voters; his supporters were that loyal.

Vehicles passing a sign on Ninth Avenue about New York City’s congestion pricing programme.

PHOTO: REUTERS

I passed the Empire State Building, at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and West 34th Street, without catching a glimpse of the iconic structure. The traffic was moving well.

The 102-storey art deco skyscraper has long lost the claim to being the tallest building in the world, but four million tourists still make the trip to its observation decks to peer at the cityscape. Faintly acrophobic, I quickly dismissed the thought of going up to see what the traffic might look like from up there.

In any case, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which administers the toll, has done the maths. The vehicle flow into the congestion relief zone – which is the long tip of Manhattan south of 60th Street – fell 7.5 per cent in the first week the toll was introduced.

In the morning rush hours, drive times into the zone fell anywhere from 10 per cent (across the Manhattan Bridge) to 39 per cent (the Lincoln and Queens-Midtown tunnels) to 65 per cent (the Holland Tunnel).

A sign in New York’s Meatpacking District announcing that the city’s congestion pricing programme is in effect.

ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

Afternoon-peak journey times across Manhattan fell between 4 per cent and 36 per cent.

Bus riders saw commute time shrink by 5 per cent to 28 per cent.

Private cars make up about a third of Manhattan traffic of about 400,000 vehicles which cross into Manhattan every day. The bulk of the traffic, 53 per cent, is made up by the city’s iconic yellow cabs and for-hire services like Uber and Lyft. Buses are at only 4 per cent, while trucks and vans make up the rest.

The new toll has brought on a tidal wave of snorts and some loud claps from the residents, always short of time, never of opinion.

“I think this is a fantastic change for the city and it has been a serious success,” said Mr Wyatt Goodwin, a resident who works with a global research and advisory firm.

“Streets seem less crowded, subway cars are more full – which is a good thing – and it seems like we’re poised to bring in some additional funding for the community,” he said.

Cars have been a major burden for average New Yorkers, leading to devastating traffic accidents and terrible pollution, he added. Congestion pricing would help address that, he said.

“In a city full of bureaucracy, this is a real achievement in improving our day-to-day lives.”

Like three-quarters of people coming into Manhattan, he uses public transport to get to work.

Less clued in but not less excited was Mr Jose Ramos, a parking attendant supervisor on Wall Street.

He wasn’t sure whether it might impact his business if fewer cars came into the city. “Not yet,” he said, shrugging. “We’ll see if it even lasts.”

But he was certain of the motive behind the toll, which has riled half of the city’s population, according to some polls.

“Our city officials just love to get the cash registers ringing,” he said.

He’s not wrong. The MTA hopes to raise US$15 billion in bond financing on the back of revenue through the toll, which will help update the mass transit system.

For others, it feels like an unfair imposition when times are already hard.

“We live in the most expensive city in the country, so I have to ask if we really need to fork out more for the privilege of just driving to work or meeting a friend for lunch,” said Ms Karina Heisman, a stay-at-home mother of a toddler from Queens. Waiting for a cab, she said she had elected not to drive in for her occasional trips downtown.

“But if it is our law, we ought to respect it and pay up,” she added.

This is hardly a popular sentiment.

Mayor Eric Adams anticipates that collecting the tolls will not be without its challenges. “There is going to be an entirely new industry on how to evade tolls,” he said, calling it the “ingenuity” of mankind.

The city is soon coming up with new rules stipulating that car number plates must be kept clean, free from dirt, rust, glass or plastic coverings, or materials that could render them unreadable by the 1,400 traffic cameras and electronic toll readers that were set up for congestion pricing in Manhattan.

What worries analysts, though, is that the fall in vehicular traffic has not come with a corresponding rise in the use of buses or trains. The city authorities noted that “no meaningful uptick in transit ridership” has been registered to date.

That’s not a very comforting indicator for the city’s economic vitality, for its businesses which depend on walk-in customers to survive.

Trump, a New Yorker himself, is among those who want the toll gone. It would be virtually impossible for New York to fully come back from the lingering Covid-19 business slowdown as long as the congestion tax is in effect, he said.

But it’s not clear exactly how he could undo a programme passed by the state legislature and approved by the Biden administration.

For now, New Yorkers must decide: Embrace the US$9 cure or go back to the days of gridlocks, frenzy and drama.

Bhagyashree Garekar is The Straits Times’ US bureau chief. Her previous key roles were as the newspaper’s foreign editor (2020-2023) and as its US correspondent during the Bush and Obama administrations.