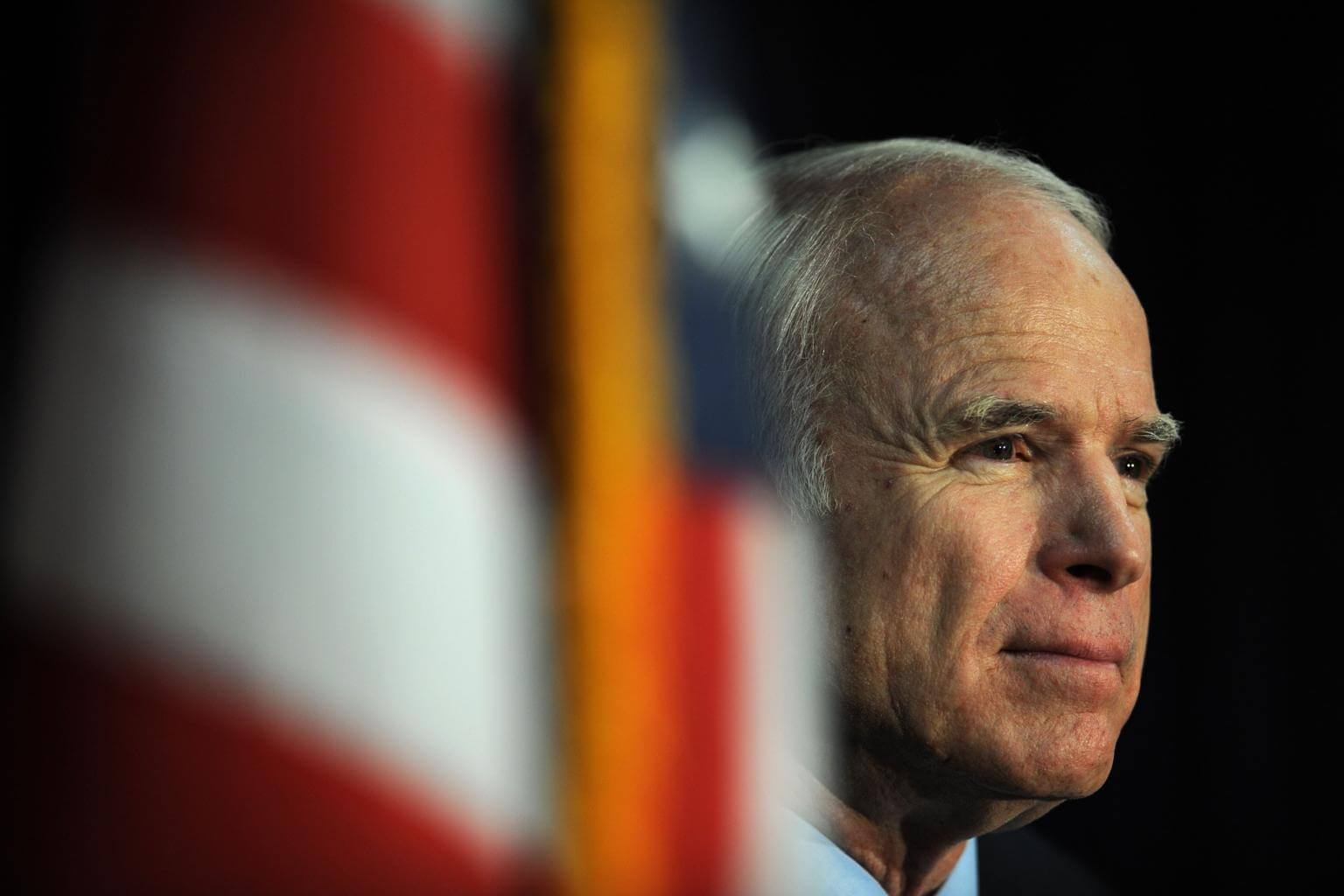

John McCain, unbridled titan of American politics

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

In his memoir The Restless Wave, US Senator John McCain wrote: "It's been quite a ride. I've known great passions, seen amazing wonders, fought in a war, and helped make peace... I've lived very well and I've been deprived of all comforts. I've been as lonely as a person can be and I've enjoyed the company of heroes. I've suffered the deepest despair and experienced the highest exultation. I made a small place for myself in the story of America and the history of my times."

PHOTO: AFP

WASHINGTON (AFP, REUTERS) - John Sidney McCain III had but one employer throughout his iconic and tempestuous career: the United States of America.

It was a family tradition. Mr McCain was a direct descendant, he claimed, of a captain in George Washington's army during the Revolutionary War.

And like his father and grandfather before him, each four-star admirals named John McCain, he lived in the service of his country: First as a US Navy fighter pilot, then as a lawmaker until his death on Saturday (Aug 25) at age 81, following a brain cancer diagnosis in the summer of 2017.

He, too, might have become an admiral, if a Soviet-made surface-to-air missile had not cut short his own high-flying military trajectory on Oct 26, 1967.

On the day of his 23rd mission over Vietnam, his A-4 Skyhawk was hit as he flew across Hanoi's skies.

Mr McCain ejected and parachuted into a small lake in the centre of town, where he was nearly lynched by a furious mob. His two arms and right knee were badly broken.

With his father the commander of all US forces in the Pacific, Mr McCain would remain a prisoner of war for more than five years.

He was released in 1973 after the Paris Peace Accords, but the physical consequences of his deliberately ill-treated fractures - and torture in prison - would cost him his career as a pilot.

"For some reason, it was not my time then, and I do believe that therefore because of that, that I was meant to do something," he said in a 1989 interview.

Political maverick

That something, it became clear, would be politics. After a few years as the Navy's Senate liaison, Mr McCain moved to Arizona, the home state of his second wife, and won a seat in the US House of Representatives in 1982.

His ambitions grew, and he rose quickly to the Senate, the most powerful political body in America. It became his second home for 30 years.

Mr McCain long cultivated the image of a Republican maverick, defying his party on issues ranging from campaign finance reform to immigration.

He saw little use for party discipline, an attitude reinforced by his past episodes of rebellion - as an unruly student at the US Naval Academy, or a hotheaded prisoner provoking his Vietnamese jailers.

"Surviving my imprisonment strengthened my self-confidence, and my refusal of early release taught me to trust my own judgment," Mr McCain wrote in his 1999 memoir Faith Of My Fathers.

It was this unorthodox, unbridled McCain, disdainful of authority and occasionally arrogant, who threw his hat in the ring in the 2000 presidential race.

A self-proclaimed "straight talk" campaigner, he offered Americans his moderate-right vision, while keeping at arm's length the Christian conservatives that his opponent Mr George W. Bush had successfully seduced.

Mr McCain came up short, but solidified his stature and eventually seized the Republican torch from the unpopular president Bush.

In 2008, he made peace with the party establishment, and finally won the presidential nomination.

With the White House within reach, he made an instinctive - and deeply controversial - call. Many of his associates would never forgive him for choosing as his running mate a virtual unknown, the untested Alaska governor Sarah Palin.

The decision helped usher in the grassroots Tea Party revolution and the rise of populism later embodied by Mr Donald Trump.

In his new book, Mr McCain voiced regret for not choosing then-Senator Joe Lieberman, a Democrat turned independent, as his running mate.

Mr McCain wrote that he had originally settled on Mr Lieberman, Democrat Al Gore's running mate in the 2000 election, but was warned by Republican leaders that Mr Lieberman's views on social issues, including support for abortion rights, would "fatally divide" the party.

"It was sound advice that I could reason for myself," Mr McCain wrote. "But my gut told me to ignore it and I wish I had."

Mr Barack Obama won 53 per cent of the vote to Mr McCain's 45.6 per cent.

Mr McCain, now twice defeated, took to joking about how he started sleeping like a baby: "Sleep two hours, wake up and cry, sleep two hours, wake up and cry."

Dismayed by Trump

Mr McCain had a famous temper and rarely shied away from a fight. He had several with Mr Trump.

He was the central figure in one of the most dramatic moments in Congress of Mr Trump's presidency when he returned to Washington shortly after his brain cancer diagnosis for a middle-of-the-night Senate vote in July 2017. Still bearing a black eye and scar from surgery, Mr McCain gave a thumbs-down signal in a vote to scuttle a Trump-backed bill that would have repealed the Obamacare healthcare law and increased the number of Americans without health insurance by millions.

Mr Trump was furious about Mr McCain's vote and frequently referred to it at rallies, but without mentioning Mr McCain by name.

Mr McCain could work a crowd. In Washington, he held court with reporters in the halls of Congress, at times pithy and impatient.

"That's a dumb question," he told one probing journalist.

But the snappy tone could turn to self-deprecation. "I don't think I'm a very smart guy," he once said.

He could also be volcanic, especially about causes dear to him: the armed forces, American exceptionalism and, in his later years, the threat posed by Russia's Vladimir Putin, whom he branded "a murderer and a thug".

Mr McCain's fellow Republicans occasionally mocked his interventionist reflexes, noting he could never say no to a war. After all, he once referenced a Beach Boys tune when singing about whether to "bomb bomb bomb" Iran.

To the end, Mr McCain remained convinced that America's values should be shared and defended worldwide.

He routinely hopped a flight to Baghdad, Kabul, Taipei or revolution-wracked Kiev, and was received more like a head of state than a lawmaker.

After the annexation of Crimea, Russia placed his name on a blacklist in retaliation for US-led sanctions.

"I guess this means my spring break in Siberia is off," he shot back.

Regarding Russia or Syria, Mr McCain's voice carried far. But the senator was in effect a general without an army.

Mr Trump's election seemed to trample on the struggles and ideals of the veteran Republican, who quickly grew dismayed by the billionaire businessman's nationalism and protectionism, his flirtation with Mr Putin and his seeming contempt for the dignity of the office of president.

He even took issue with Mr Trump's multiple draft deferments during the Vietnam War, granted after he was diagnosed with bone spurs in his foot.

Quite a ride

But none of it made Mr McCain want to recede into happy retirement. Perhaps, thinking of his grandfather, who died just days after returning home following Japan's surrender in World War II, Mr McCain sought to remain in the Senate for as long as he could, even faced with a diagnosis of aggressive brain cancer.

Since December 2017, he was kept away from the Senate floor as he underwent treatment in Arizona - and received at his ranch a steady stream of friends and colleagues come to bid him farewell, away from the media gaze.

In a memoir published in May, Mr McCain wrote that he hated to leave the world, but had no complaints.

"It's been quite a ride. I've known great passions, seen amazing wonders, fought in a war, and helped make peace," Mr McCain wrote.

"I've lived very well and I've been deprived of all comforts. I've been as lonely as a person can be and I've enjoyed the company of heroes. I've suffered the deepest despair and experienced the highest exultation.

"I made a small place for myself in the story of America and the history of my times."

On the eve of his death, his family announced that he was ending his treatment.

Mr McCain let it be known in his memoir published in May, The Restless Wave, that he wished to be laid to rest in Maryland, near his old Navy pal Chuck Larson.

He is survived by his wife Cindy and seven children, three of them from a previous marriage.