Inside Trump's coronavirus meltdown

From denial to acceptance to suggesting disinfectant injections as a cure, US leader's erratic decisions have clouded country's Covid-19 response

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

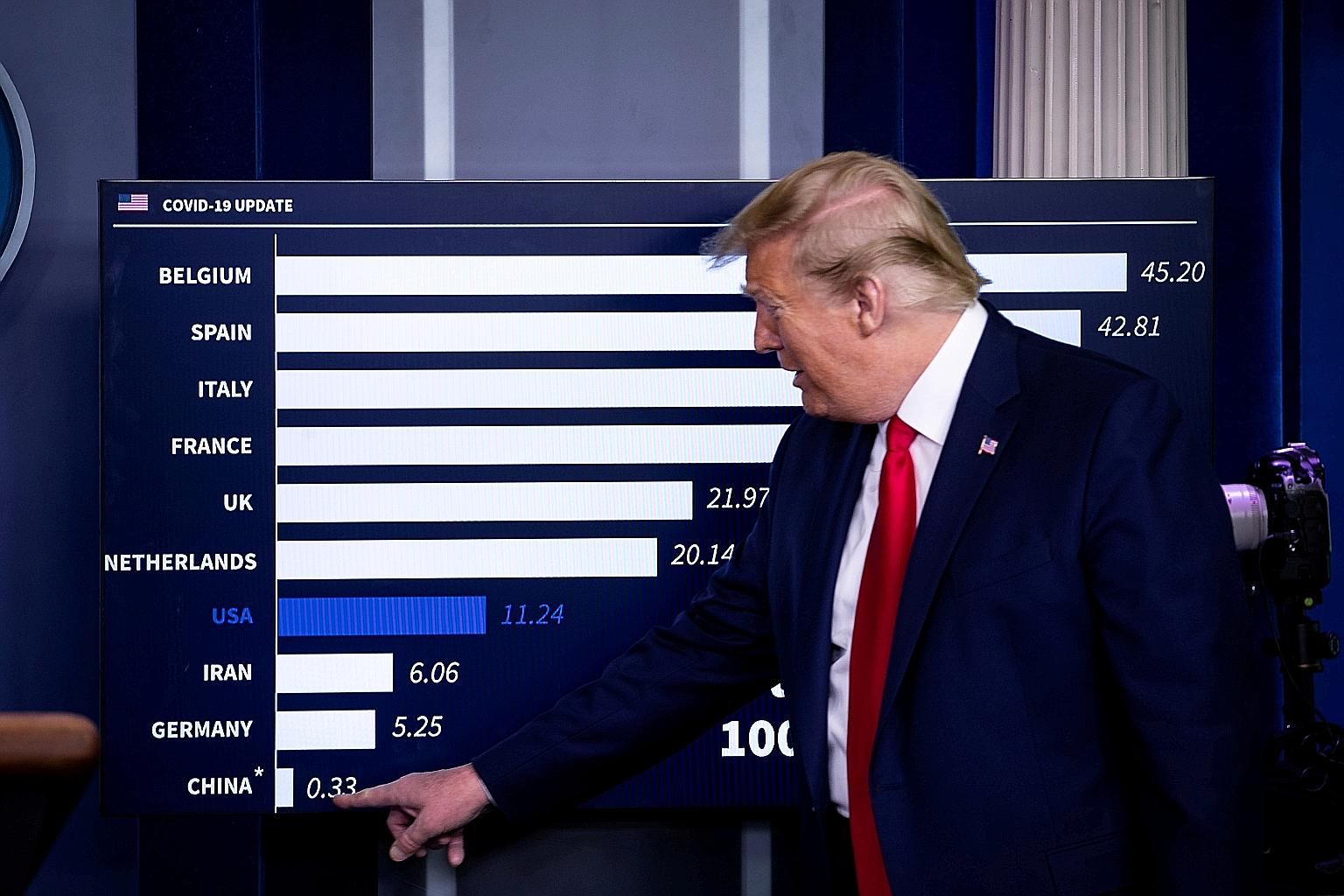

US President Donald Trump pointing at China's figures on a chart showing daily mortality cases, during a daily coronavirus briefing on April 18. His overriding goal is to revive the economy before the general election. Mr Trump and his son-in-law Jared Kushner have all but declared mission accomplished on the pandemic.

PHOTO: REUTERS

When the history is written of how America handled the global era's first real pandemic, March 6 will leap out of the timeline.

That was the day President Donald Trump visited the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta. His foray to the world's best disease research body was meant to showcase that America had everything under control. It came midway between the time he was still denying the coronavirus posed a threat and the moment he said he had always known it could ravage America.

Shortly before the CDC visit, he said "within a couple of days, (infections are) going to be down to close to zero". The US then had 15 cases. "One day, it's like a miracle, it will disappear." A few days later, he claimed: "I've felt it was a pandemic long before it was called a pandemic."

That afternoon at the CDC provides an X-ray into Mr Trump's mind at the halfway point between denial and acceptance.

We now know Covid-19 had already passed the breakout point in the US. The contagion had been spreading for weeks in New York, Washington state and other clusters. The curve was pointing sharply upwards. Mr Trump's goal in Atlanta was to assert the opposite.

He dismissed CNN as fake news, boasted about his high Fox News viewership, cited the US stock market's recent highs, called Washington state's Democratic governor a "snake" and admitted he hadn't known that large numbers of people could die from ordinary flu.

He also misunderstood a question on whether he should cancel campaign rallies for public health reasons. "I haven't had any problems filling (the stadiums)," he said.

What caught the media's attention were two comments he made about Covid-19. There would be four million testing kits available within a week. "The tests are beautiful," he said. "Anybody that needs a test gets a test."

Ten weeks later, that is still not close to being true. Fewer than 3 per cent of Americans had been tested by the middle of this month.

Mr Trump also boasted about his grasp of science. He cited a "super genius" uncle, Mr John Trump, who taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and implied he inherited his intellect. "Every one of these doctors said, 'How do you know so much about this?' Maybe I have a natural ability," he said.

What the headlines missed was a boast that posterity will take more seriously than his self-estimated IQ or the exaggerated test numbers (the true number of CDC kits by March was 75,000).

Mr Trump proclaimed that the US was leading the world. South Korea had its first infection on Jan 20, the same day as America's first case, and was, he said, calling the US for help. "They have a lot of people that are infected; we don't. All I say is, 'Be calm'. Everyone is relying on us. The world is relying on us."

He could just as well have said baseball is popular or foreigners love New York. American leadership in any disaster, whether a tsunami or an Ebola outbreak, has been a truism for decades. The US is renowned for helping others in an emergency.

In hindsight, Mr Trump's claim to global leadership leaps out. History will mark Covid-19 as the first time that ceased to be true. US airlifts have been missing in action. America cannot even supply itself.

South Korea, which has a population density nearly 15 times greater and is next door to China, has lost 259 lives to Covid-19. There have been days when America has lost 10 times that number. The US death toll is now approaching 90,000.

WHAT HAS GONE WRONG?

I interviewed dozens of people, including outsiders who Mr Trump consults regularly, former senior advisers, World Health Organisation officials, scientists and diplomats, and figures inside the White House. Some spoke off the record.

Again and again, the story that emerged is of a president who ignored increasingly urgent intelligence warnings from January, dismisses anyone who claims to know more than him and trusts no one outside a tiny coterie, led by his daughter Ivanka and her husband Jared Kushner, the property developer who Mr Trump has empowered to sideline the best-funded disaster response bureaucracy in the world.

People often observed during Mr Trump's first three years that he had yet to be tested in a true crisis. Covid-19 is way bigger than that.

"Trump's handling of the pandemic at home and abroad has exposed more painfully than anything the meaning of America First," says Mr William Burns, head of the Carnegie Endowment. "America is first in the world in deaths, first in the world in infections and we stand out as an emblem of global incompetence. The damage to America's influence and reputation will be very hard to undo."

The psychology behind Mr Trump's inaction on Covid-19 was on display that afternoon at the CDC. The unemployment numbers had come out that morning. The US had added 273,000 jobs in February, bringing the jobless rate down to a near record low of 3.5 per cent. His re-election chances were looking 50:50 or better. The previous Saturday, Mr Joe Biden had won the South Carolina primary. But the Democratic contest still seemed to have miles to go. Nothing could be allowed to frighten the Dow Jones.

Any signal that the US was bracing itself for a pandemic - including taking actual steps to prepare for it - was discouraged.

"Jared had been arguing that testing too many people, or ordering too many ventilators, would spook the markets and so we just shouldn't do it," says a Trump confidant. "That advice worked far more powerfully on him than what the scientists were saying. He thinks they always exaggerate."

In fairness, other democracies, notably the United Kingdom, Italy and Spain, also wasted time failing to prepare for the approaching onslaught. Whoever was America's president might have been equally ill-served by Washington infighting.

The CDC has been plagued by mishap and error throughout the crisis. The agency spent weeks trying to develop a jinxed test when it could simply have imported WHO-approved kits from Germany, which has been making them since late January. A former senior adviser in the Trump White House said: "Because of the CDC's errors, we did not have a true picture of the spread of the disease."

Here again, Mr Trump's stamp is clear. It was Mr Trump who chose Mr Robert Redfield to head the CDC in spite of warnings about the former military officer's controversial record. Mr Redfield led the Pentagon's response to HIV-Aids in the 1980s. It involved isolating suspected soldiers in so-called HIV Hotels. Many who tested positive were dishonourably discharged, some committed suicide.

A devout Catholic, Mr Redfield saw Aids as the product of an immoral society. For many years, he championed a much-hyped remedy that was discredited in tests. That debacle led to his removal in 1994.

"Redfield is about the worst person you could think of to be heading the CDC at this time," says Ms Laurie Garrett, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science journalist who has reported on epidemics. "He lets his prejudices interfere with the science, which you cannot afford during a pandemic."

One of the CDC's constraints was to insist on developing its own test rather than import a foreign one.

Dr Anthony Fauci, the infectious disease expert, is known to loathe Mr Redfield, and vice versa. That meant the CDC and Mr Fauci's National Institutes of Health were not on the same page.

"The last thing you need is scientists fighting with each other in the middle of an epidemic," says Dr Kenneth Bernard, who set up a White House pandemic unit in 2004, which was scrapped under former president Barack Obama and revived after Ebola struck in 2014.

The scarcity of kits meant that scientists lacked a picture of America's rapidly spreading infections. The CDC was forced to ration tests to "persons under investigation" - people who had come within six feet (1.8m) of someone who had either visited China or been infected with Covid-19 in the previous 14 days. Most were denied. Few could prove they had met either criterion. This was at a time when several countries, notably Germany, Taiwan and South Korea, gave access to on-the-spot tests.

"You've been commuting by train or subway into New York every day, you show up sick in the clinic and they refuse to test you because you can't prove you've been within six feet of someone with Covid-19," says the former adviser. "You've probably been close to half a million people in the previous two weeks."

By March 11, just five days after Mr Trump's CDC visit, the reality was beginning to seep through.

He banned travel from most of Europe, which expanded the partial ban he put on China in February. Two days later, he declared a national emergency. Even then, however, he insisted America was leading the world. "We've done a great job because we acted quickly," he said. "We acted early."

Over the next 48 hours, however, something snapped in his mind.

Citing a call with one of his sons, Mr Trump said on March 16: "It's bad. It's bad… They think August (before the disease peaks). Could be July. Could be longer than that."

Eleven days later, Britain's Prime Minister Boris Johnson contracted Covid-19. The disease nearly killed him. That was Mr Johnson's road to Damascus. Many hoped Mr Trump had had a similar conversion. If so, it did not last long. The next week, he was saying America should reopen by Easter on April 12.

Mr Trump's mindset became increasingly surreal. He began to tout hydroxychloroquine as a cure for Covid-19. On March 19, at a televised briefing, which he held daily for five weeks, often rambling for more than two hours, he depicted the anti-malarial drug as a potential magic bullet. It could be "one of the biggest game-changers in the history of medicine", he later tweeted.

His leap of faith, which was inspired by Fox News anchors and his lawyer Rudy Giuliani, none of whom have a medical background, turned Washington's bureaucracy upside-down.

Scientists who demurred were punished. Mr Rick Bright, the federal scientist in charge of developing a vaccine, was removed last month after blocking efforts to promote hydroxychloroquine.

Most clinical trials have shown the drug has no positive impact on Covid-19 patients and can harm people with heart problems. "I was pressured to let politics and cronyism drive decisions over the opinions of the best scientists in government," Mr Bright said in a statement.

In a whistle-blower complaint, he said he was pressured to send millions of dollars worth of contracts to a company controlled by a friend of Mr Kushner. When he refused, he was fired. The US Department of Health and Human Services denied his allegations.

An administration official says advising Mr Trump is like "bringing fruits to the volcano", Mr Trump being the lava source. "You're trying to appease a great force that's impervious to reason," says the official.

When Mr Trump suggested last month that people could stop Covid-19 or even cure themselves by injecting disinfectant such as Lysol or Dettol, his chief scientist Deborah Birx did not dare contradict him. The leading bleach companies issued statements urging customers not to inject or ingest disinfectant because it could be fatal. The CDC only issued a cryptic tweet advising Americans to "follow the instructions on the product label".

Mr Trump's dog-eat-dog instinct has been just as strong abroad as at home. A meeting of the G-7 foreign ministers in March failed to agree on a statement after US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo insisted they brand it the "Wuhan virus". America declined to participate in a recent summit hosted by French President Emmanuel Macron to collaborate on a vaccine.

Most dramatically, Mr Trump has suspended US funding of the WHO, which he says covered up for China's lying.

Other critics say the Geneva-based body was too ready to take Beijing's word at face value. There is some truth to that claim. "They were too scared of offending China," says Mr Bernard, who was America's WHO director for two years. But its bureaucratic timidity did not stop other countries from taking early precautions.

Mr Trump alleged the WHO's negligence had increased the world's death rate "twenty-fold". In practice, the body must always abide by member state limits, especially the big ones, notably the US and China. That is the reality for all multilateral bodies. The WHO nevertheless declared an international emergency six weeks before Mr Trump's US announcement. WHO officials say Mr Trump's move has badly hindered its operations.

"You don't turn off the hose in the middle of the fire, even if you dislike the fireman," says WHO chief of staff Bernhard Schwartlander.

So where does the American chapter of the plague go from here?

Early into his partial about-turn, Mr Trump said scientists told him that up to 2.5 million Americans could die of the disease. The most recent estimates suggest 135,000 Americans will die by late July. That means two things.

First, Mr Trump will tell voters he has saved millions of lives. Second, he will continue to push aggressively for US states to lift their lockdown. His overriding goal is to revive the economy before the general election. Mr Trump and Mr Kushner have all but declared mission accomplished on the pandemic. "This is a great success story," said Mr Kushner in late April. "We have prevailed," said Mr Trump last week.

Economists say a V-shaped recovery is unlikely. Even then, it could be two Vs stuck together - a W, in other words. The social mingling resulting from any short-term economic reopening would probably come at the price of a second contagious outburst. As long as the second V begins only after November, Mr Trump might just be re-elected.

"From Trump's point of view, there is no choice," said Mr Charlie Black, a senior Republican consultant. "It is the economy or nothing. He can't exactly run on his personality."

Mr Steve Bannon, Mr Trump's former chief strategist, said: "Trump's campaign will be about China, China, China. And hopefully the fact that he rebooted the economy."

Mr Trump has been persuaded to cease his daily briefings. The White House internal polling shows his once double-digit lead over Mr Biden among Americans over 65 has been wiped out. It turns out retirees are no fans of herd immunity.

Mr Trump's friends are trying to figure out how to return life to normal without provoking a new death toll. His poll numbers have been steadily dropping over the last month. For the next six months, America's microbial fate will be in the hands of its president's erratic re-election strategy.

FINANCIAL TIMES