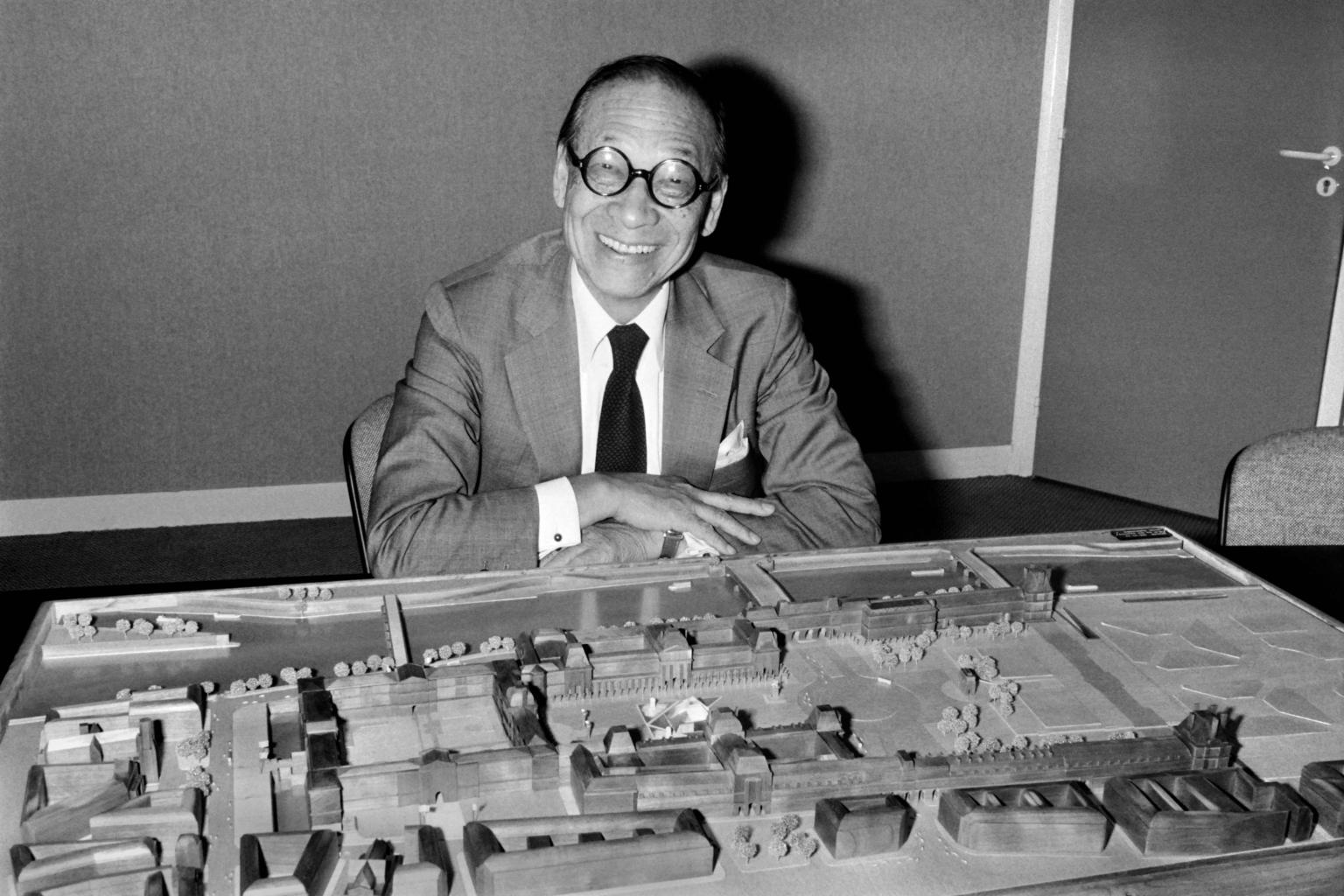

I.M. Pei, world-renowned architect, dies aged 102

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Chinese-born American architect I. M. Pei died at age 102. Among other accomplishments, he was known for designing the glass pyramid that serves as an entry for the Louvre in Paris.

PHOTO: AFP

Follow topic:

NEW YORK (NYTIMES) - I.M. Pei, the Chinese-born American architect who began his long career working for a New York real-estate developer and ended it as one of the most revered architects in the world, has died. He was 102.

His son Chien Chung Pei said on Thursday (May 16) that his father had died overnight.

Mr Pei was probably best known for designing the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the glass pyramid that serves as an entry for the Louvre in Paris.

In Singapore, he was responsible for three landmarks - OCBC Centre, Raffles City and the trapezoidal The Gateway in Beach Road.

He was hired by Mr William Zeckendorf's Webb & Knapp in 1948 before establishing his own architectural firm in 1955. In its early years, I. M. Pei & Associates mainly executed projects for Mr Zeckendorf, including Kips Bay Plaza in New York, finished in 1963; Society Hill Towers in Philadelphia (1964); and Silver Towers in New York (1967). All were notable for their gridded concrete facades.

The firm became fully independent from Webb & Knapp in 1960, by which time Mr Pei, a cultivated man whose quiet, understated manner and easy charm masked an intense, competitive ambition, was winning commissions for major projects that had nothing to do with Mr Zeckendorf.

Among these were the National Centre for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, completed in 1967, and the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse and the Des Moines Art Centre, both finished in 1968.

They were the first in a series of museums he designed that would come to include the East Building (1978) and the Louvre pyramid (1989) as well as the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland, for which he designed what amounted to a huge glass tent in 1995. It was perhaps his most surprising commission.

Mr Pei, not a rock 'n' roll fan, initially turned down the job. After he changed his mind, he prepared for the challenge of expressing the spirit of the music by travelling to rock concerts with Mr Jann Wenner, the publisher of Rolling Stone.

The Cleveland project would not be Mr Pei's last unlikely museum commission: His museum oeuvre would culminate in the call to design the Museum of Islamic Art, in Doha, Qatar, in 2008 - a challenge Mr Pei accepted with relish.

A long-time collector of Western Abstract Expressionist art, he admitted to knowing little about Islamic art.

As with the Rock and Roll museum, Mr Pei saw the Qatar commission as an opportunity to learn about a culture he did not claim to understand. He began his research by reading a biography of the Prophet Muhammad, and then commenced a tour of great Islamic architecture around the world.

Modernism meets tradition

While the waffle-like concrete facades of the Zeckendorf buildings were an early signature of his, Mr Pei soon moved beyond concrete to a more sculptural but equally modernist approach.

Throughout his long career, he combined a willingness to use bold, assertive forms with a pragmatism born in his years with Mr Zeckendorf, and he alternated between designing commercial projects and making a name for himself in other architectural realms.

Besides his many art museums, he designed concert halls, academic structures, hospitals, office towers and civic buildings like the Dallas City Hall, completed in 1977; the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, finished in 1979; and the Guggenheim Pavilion of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, finished in 1992.

I.M. Pei & Associates eventually became I.M. Pei & Partners, and later, Pei, Cobb and Freed.

When Mr Pei was invited to design the East Building of the National Gallery of Art, he had the opportunity to demonstrate his belief that modernism was capable of producing buildings with the gravitas, the sense of permanence and the popular appeal of the greatest traditional structures.

When the building opened in 1978, Ms Ada Louise Huxtable, the senior architecture critic of The New York Times, hailed it as the most important building of the era, and she called Mr Pei, at least by implication, the pre-eminent architect of the time.

Most other critics also praised Mr Pei's angular structure of glass and marble, constructed out of the same Tennessee marble as John Russell Pope's original National Gallery Building of 1941, reshaped into a building of crisp, angular forms set around a triangular courtyard.

Mr Pei, many critics said, had found a way to get beyond both the casual, temporal air and the coldness of much modern architecture, and to create a building that was both boldly monumental and warmly inviting, even exhilarating.

In 1979, the year after the National Gallery was completed, Mr Pei received the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects, its highest honour.

At the same time that he was receiving plaudits in Washington, however, Mr Pei was recovering from one of the most devastating setbacks any architect of his generation had faced anywhere: the nearly total failure of one of his most conspicuous projects, the 700-foot-tall John Hancock Tower at Copley Square in Boston.

A thin, elegant slab of bluish glass designed by his partner Henry Cobb, it was nearing completion in 1973 when sheets of glass began popping out of its facade. They were quickly replaced with plywood, but before the source of the problem could be detected, nearly a third of the glass had fallen out, creating both a professional embarrassment and an enormous legal liability for Mr Pei and his firm.

The fault, experts believed, was not in the Pei design but in the glass itself: the Hancock Tower was one of the first high-rise buildings to use a new type of reflective, double-paned glass.

The building ultimately won numerous awards, including the American Institute of Architects' 25-Year Award. But it took eight years of legal wrangling, millions of dollars and the replacement of all 10,344 panes of glass in the facade before the Hancock's troubles could be put to rest and the building could be appreciated as one of the most beautiful skyscrapers of the late 20th century.

Ieoh Ming Pei was born in Canton (now Guangzhou) on April 26, 1917, the son of Tsuyee Pei, one of China's leading bankers.

When he was an infant, his father moved the family to Hong Kong to assume the head position at the Hong Kong branch of the Bank of China, and when Ieoh Ming was nine, his father was put in charge of the larger branch in Shanghai. He remembered being fascinated by the construction of a 25-storey hotel.

"I couldn't resist looking into the hole," he recalled in 2007. "That's when I knew I wanted to build."