How US foreign aid cuts are setting the stage for disease outbreaks

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The loss of funding for even programmes with waivers is likely to result in more than 28,000 new cases of infectious diseases such as Ebola and Marburg, and 200,000 cases of paralytic polio each year.

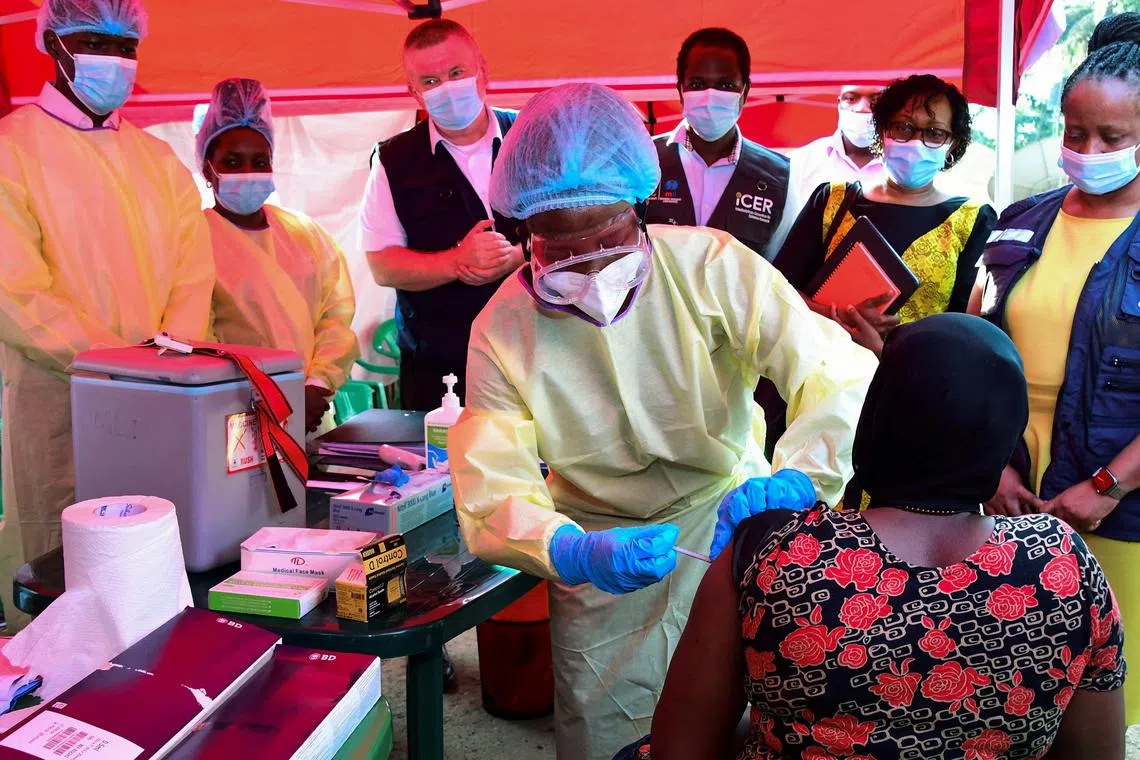

PHOTO: REUTERS

NEW YORK - Dangerous pathogens left unsecured at laboratories across Africa. Halted inspections for mpox, Ebola and other infections at airports and other checkpoints. Millions of unscreened animals shipped across borders.

The Trump administration’s pause on foreign aid has hobbled programmes that prevent and snuff out outbreaks around the world, scientists say, leaving people everywhere more vulnerable to dangerous pathogens.

That includes Americans.

Outbreaks that begin overseas can travel quickly: The coronavirus may have first appeared in China, for example, but it soon appeared everywhere, including the US. When polio or dengue appears in the US, cases are usually linked to international travel.

“It’s actually in the interest of American people to keep diseases down,” said Dr Githinji Gitahi, who heads Amref Health Africa, a large non-profit organisation that relies on the US for about 25 per cent of its funding.

“Diseases make their way to the US, even when we have our best people on it, and now we are not putting our best people on it,” he added.

In interviews, more than 30 current and former officials of the US Agency for International Development (USAid), members of health organisations and experts in infectious diseases described a world made more perilous than it was just a few weeks ago.

Many spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation by the federal government.

The timing is dire: Congo is experiencing the deadliest mpox outbreak in history, with cases exploding in a dozen other African countries.

The US is home to a worsening bird flu crisis. Multiple haemorrhagic fever viruses are smouldering: Ebola in Uganda, Marburg in Tanzania, and Lassa in Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

In 2023, USAid invested about US$900 million (S$1.2 billion) to fund labs and emergency response preparedness in more than 30 countries. The pause on foreign aid froze those programmes. Even payments to grantees for work already completed are being sorted out in the courts.

Waivers issued by the State Department were intended to allow some work to continue on containing Ebola, Marburg and mpox, as well as preparedness for bird flu.

But Trump administration appointees choked payment systems and created obstacles to implementing the waivers, according to a USAid memo by Mr Nicholas Enrich, who was the agency’s acting assistant administrator for global health until March 2.

In February, the Trump administration cancelled about 5,800 contracts,

“It was finally clear that we were not going to be implementing” even programmes that had waivers, Mr Enrich recalled in an interview.

The decision is likely to result in more than 28,000 new cases of infectious diseases such as Ebola and Marburg and 200,000 cases of paralytic polio each year, according to one estimate.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio has been working diligently since being sworn in to review every dollar spent, the State Department said in an e-mailed statement.

“We’ll be able to say that every programme that we are out there operating serves the national interest, because it makes us safer or stronger or more prosperous,” the statement quoted Mr Rubio as saying.

Most USAid staff saw their employment terminated

Now it has six.

Those who were fired included the organisation’s leading expert in lab diagnostics and the manager of the Ebola response. One official who was let go said: “I have no idea how six people are going to run four outbreak responses.”

Also sent home were hundreds of thousands of community health workers in Africa who were sentinels for diseases.

In early January, the Tanzanian government denied that there were new cases of Marburg, a haemorrhagic fever. It was a community health worker trained through a US-funded Ebola programme who reported the disease a week later.

The outbreak eventually grew to include 10 cases; it is now under control, the government has said.

Even in quieter times, foreign aid helps to prevent, detect and treat diseases that can endanger Americans, including drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus, tuberculosis and malaria, and bacteria that do not respond to available antibiotics.

Much of that work has stopped, and other organisations or countries cannot fill the gap.

Compounding the loss is America’s withdrawal from the World Health Organisation (WHO), which has instituted cost-cutting measures of its own.

“This is a lose-lose scenario,” said Dr Keiji Fukuda, who has led pandemic prevention efforts at WHO and the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The slashing of foreign aid not only deprives the world of American leadership and expertise, but it also locks the US out of global discussions, he added. “For the life of me, I cannot see the justification or the reason for this very calculated, systematic approach to pull down public health.”

Trying to adapt

USAid’s intense focus on global health security is barely a decade old, but it has mostly received bipartisan support. The first Trump administration expanded the programme to 50 countries.

Much of the aid was intended to help these countries eventually tackle problems on their own. And to some extent, that was happening.

But confronted with a new virus or outbreak, “there’re so many things that one has to do and learn, and many countries can’t do that on their own”, said Dr Lucille Blumberg, an infectious diseases physician and expert on emerging diseases.

USAid and its partners helped countries identify the expertise, training and machinery they needed, brought together officials in various ministries, and engaged farmers, businesses and families.

“It actually doesn’t cost the US government that much,” said an official at a large development organisation. “But that sort of trust-building, communication, sharing evidence is a real strength that the US brings to health security – and that’s gone.”

In Africa, some countries have reacted to the disappearance of aid with alarm, others with resignation.

Nigeria’s Health Minister, Dr Muhammad Ali Pate, said: “We’re doing our best to adapt to this development.

“The US government is not responsible, ultimately, for the health and the security of Nigerian people. At the end of the day, the responsibility is ours.”

A successful outbreak response requires coordination of myriad elements: investigators to confirm the initial report; workers trained to do testing; access to test kits; transport of samples; a lab with enough workers, running water, electricity and chemical supplies for diagnoses; and experts to interpret and act on the results.

In broad strokes, the CDC provided expertise on diseases, USAid funded logistics and WHO convened stakeholders, including ministries of health.

Before the aid freeze, employees from each organisation often talked every day, sharing information and debating strategy. Together, they lowered response time to an outbreak from two weeks in 2014, to five days in 2022, and to just 48 hours most recently.

But now, CDC experts who have honed their expertise over decades are not even allowed to speak to colleagues at the WHO.

USAid funding for sample transport, lab supplies, fuel for generators and phone plans for contact tracers has ended.

Much of its investment in simple solutions to seemingly intractable problems has also stopped.

In West Africa, for example, rodents that spread Lassa fever invade homes in search of food.

One programme in USAid’s Stop Spillover project introduced rodent-proof food containers to limit the problem, but it has now shut down.

In Congo, where corruption, conflict and endless outbreaks mean that surveillance “looks like Swiss cheese, even at the best of times”, the mpox response slowed because there were no health workers to transport samples, said a USAid official familiar with the response.

More than 400 mpox patients were left stranded after fleeing overwhelmed clinics.

Before a waiver restarted some work, the US identified two new cases of mpox, both in people who had travelled to East Africa.

In Kenya, USAid supported eight labs and community-based surveillance in 12 high-risk counties.

Labs in the Marsabit, Mandera and Garissa counties – which border Ethiopia and Somalia – have run out of test kits and reagents for diseases including Rift Valley fever, yellow fever and polio, and have lost nearly half their staff.

Kenya also borders Uganda and Tanzania, and is close to Congo – all battling dangerous outbreaks – and has lost more than 35,000 workers.

“These stop-work orders would mean that it increases the risk of an index case passing through unnoticed,” Dr Gitahi said, referring to the first known case in an outbreak. His organisation has terminated the services of nearly 400 of its staff of 2,400.

Many labs in Africa store samples of pathogens that naturally occur in the environment, including several that can be weaponised. With surveillance programmes shut off, the pathogens could be stolen, and a bioterrorism attack might go undetected until it is too late to counter.

Some experts are worried about bad actors who may release a threat such as cholera into the water, or weaponise anthrax or brucellosis, common in African animals. Others said they were concerned that even unskilled handling of these disease threats might be enough to set off a disaster.

Funding from the US government helped hire and train lab workers to maintain and dispose of dangerous viruses and bacteria safely. But now, pathogens can be moved in and out of labs with no one the wiser.

Ms Kaitlin Sandhaus, founder and chief executive of Global Implementation Solutions, said: “We have lost our ability to understand where pathogens are being held.”

Her company helped 17 African labs become accredited in biosafety procedures and supported five countries in drafting laws to ensure compliance. Now, the company is shutting down.

In the future, other countries, including China, will know more about where risky pathogens are housed, Ms Sandhaus said, adding: “It feels very dangerous to me.”

China has already invested in building labs in Africa, where it is cheaper and easier to “work on whatever you would like without anyone else paying attention”, said a USAid official.

Russia, too, is providing mobile labs to Ugandans in Mbale, on the border with Kenya, another official said.

Some African countries such as Somalia have fragile health systems and persistent security threats, yet minimal capacity for tracking infections that sicken animals and people, said Dr Abdinasir Yusuf Osman, a veterinary epidemiologist and chair of a working group in Somalia’s Health Ministry.

Each year, Somalia exports millions of camels, cattle and other livestock, primarily to the Middle East. The nation has relied heavily on foreign aid to screen the animals for diseases, Dr Osman said.

“The consequences of this funding shortfall, in my view, will be catastrophic and increase the likelihood of uncontrolled outbreaks,” he said.

In countries with larger economies, foreign aid has helped build relationships. Thailand is a pioneer in infectious diseases, and USAid was funding a modest project on malaria elimination that boosts its surveillance capabilities.

The abrupt end to that commitment risks losing goodwill, said Ms Jui Shah, who helped run the programme.

“In Asia, relationships are crucial for any type of work, but especially for roles that work with surveillance and patient data,” she added.

“Americans will suffer if other countries hesitate to engage with us about outbreaks.” NYTIMES