Climate change: New CO2 storage method shows potential

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

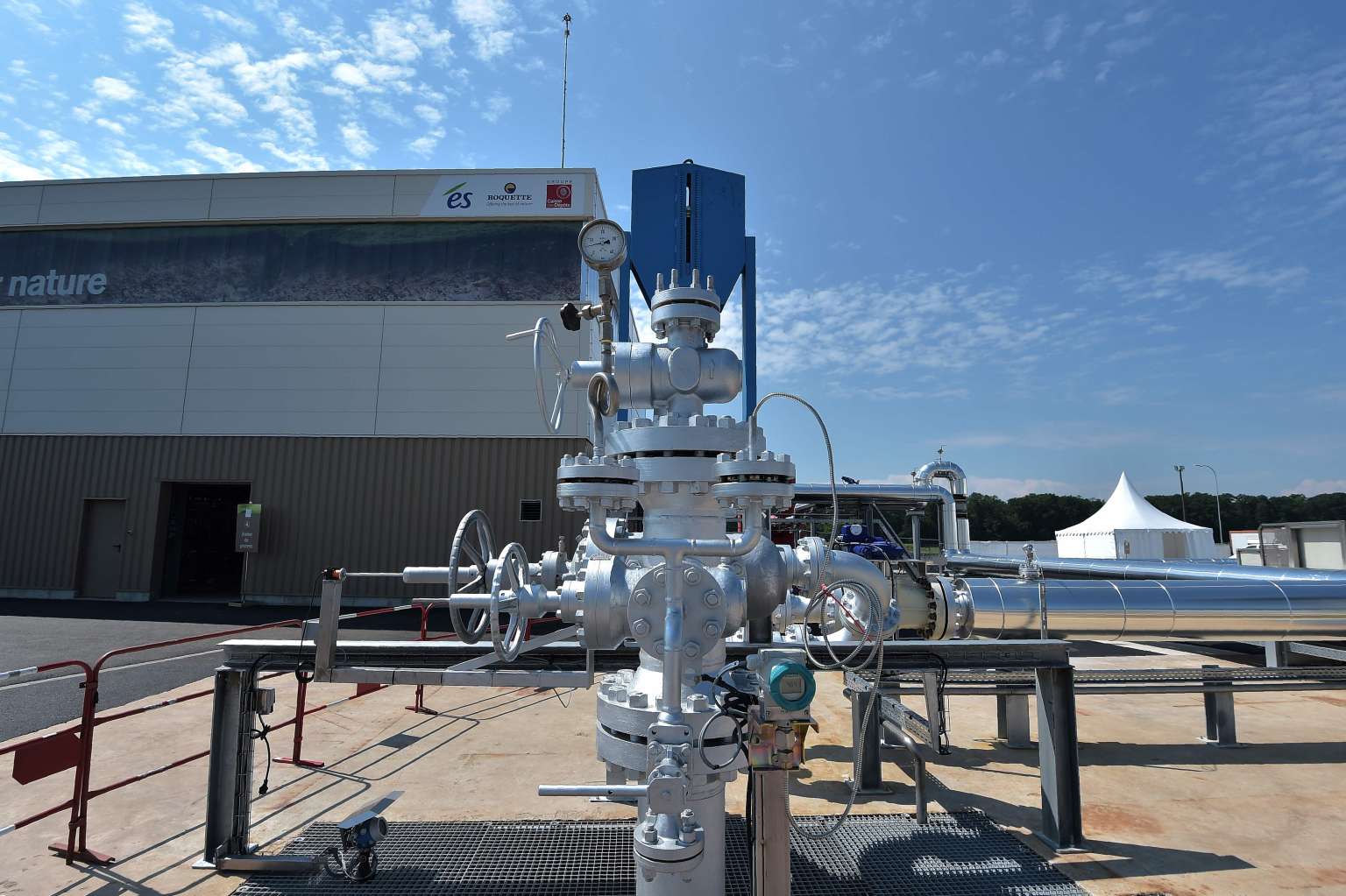

Parts of France's first deep geothermal power plant during its inauguration in Rittershoffen, eastern France, on June 7, 2016.

PHOTO: AFP

Follow topic:

WASHINGTON (AFP) - For the first time, scientists have successfully injected carbon dioxide (CO2) into volcanic basalt soil and changed it to a solid, offering a promising way to store underground the greenhouse gas linked to climate change.

Scientists were able to pump carbon emissions into the earth and change the gas to a solid for storage within months - radically faster than previous predictions that suggested the process could take hundreds or even thousands of years.

The study, appearing Thursday (June 9) in the journal Science, was part of the pilot project Carbfix launched in 2012 at Iceland's Hellisheidi geothermal power plant.

Scientists and engineers experimented with combining CO2 and other gases with water and then piping the mixture underground.

They aimed to develop a method to safely store CO2 that would otherwise escape into the atmosphere and contribute to global warming.

The Hellisheidi plant, the world's largest geothermal facility, energizes Reykjavik by pumping volcanically heated water to power turbines.

The process produces 40,000 tons of CO2 a year - just five percent of the emissions of a similarly sized coal plant, but significant nonetheless.

For years researchers have suggested limiting global warming by using carbon capture and sequestration methods like this one, but developing the technology proved challenging.

In nature, basalt in contact with CO2 and water produces a chemical reaction resulting in a chalky, white mineral. Scientists were unsure, however, how long the reaction would take: Previous studies estimated the solidification could take upwards of millennia.

The basalt under Hellisheidi proved optimal, with 95 per cent of the injected CO2 solidifying in less than two years.

"This means that we can pump down large amounts of CO2 and store it in a very safe way over a very short period of time," said study co-author Martin Stute, a hydrologist at Columbia University's Earth Observatory.

"In the future, we could think of using this for power plants in places where there's a lot of basalt - and there are many such places."

Basalt makes up most of the world's seafloors and approximately 10 per cent of continental rocks, according to the study's researchers.

A 2014 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that without carbon sequestration technology, adequately limiting global warming could prove impossible.

Most prior experiments found limited success because they injected pure CO2 into sandstone soils or deep saline aquifers, rather than first mixing the CO2 with water and then storing it in basalt.

A porous, blackish rock, basalt is rich in calcium, iron and magnesium, minerals researchers said are needed to solidify carbon for storage.