City that never sleeps struggles to find beds for illegals

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Some 850 rooms in New York’s Roosevelt Hotel in midtown Manhattan are being used to house hundreds of families who entered the US through its south-western border with Mexico.

ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

NEW YORK – The hardened cops of the New York Police Department have seen it all – gang wars, floods and fires, traffic snarls and riots. More recently, fentanyl overdose deaths,

But New York City’s latest crisis has them beat, for more reasons than one.

It is not just that the workload for the police has dramatically increased since tens of thousands of illegal immigrants began crossing the Mexican border

Overtime pay for the 36,000-strong police force hangs in the balance after New York City Mayor Eric Adams told every city agency to cut costs to fund the migrant crisis. A sum of US$12 billion (S$16.4 billion) has to be mustered from somewhere to take care of more than 100,000 illegal immigrants that the city expects to have in its shelters by 2025.

The city government’s priorities sounded off-key to two police officers who stopped for coffee at Dunkin’ Donuts in the Grand Central subway station on a rainy morning, as the city hunkered down for a passing hurricane.

“They can pay for the migrants, but hey, not our overtime,” said one officer, asking not to be named because he was not authorised to speak to the media. “We’re killing ourselves keeping crime in line. We are always understaffed, we have people quitting every month to take up other jobs. But this is way above my pay grade.”

There are other, more mundane issues: the hundreds of immigrant families who arrive daily do not speak a word of English.

“I had to use Google Translate,” said the other police officer, now serving her 15th year in uniform, when asked to describe what it was like to deal with people from Venezuela, Nicaragua, Mexico, Cuba and many other Central and South American nations. “I don’t speak Spanish. How do you tell them what to do, what not to do?”

“311 calls have increased,” she added, referring to the city hotline that residents can call for non-emergencies. “They complain about quality-of-life issues. Rubbish is piling up, the illegals are too noisy, scooters are parked all wrong.

“The residents don’t like it, the shops don’t like it.”

From luxury hotel to intake centre

The two officers from neighbouring precincts were deployed on their day off outside the iconic Roosevelt Hotel, just across the street from the subway station.

The hotel is now the main processing centre for thousands of immigrant families from Central and South America. The city authorities have not stated exactly how many are lodged in its 850 rooms. The front doors push open every few minutes to reveal a dimly lit lobby in which families huddle quietly.

New York’s Roosevelt Hotel is now the main processing centre for thousands of immigrant families from Central and South America.

ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

A 100-year-old landmark, the formerly luxurious hotel was built during the “Roaring Twenties”, after World War I. It witnessed the tumult of the Great Depression, the civic mobilisation during World War II and the rebellious pop culture of the 1960s, when the city was in the thrall of Bob Dylan’s anti-Vietnam war ballads.

The hotel’s chandeliered lobby and banquet halls have been featured in many Hollywood movies, including Maid In Manhattan and Wall Street. Pakistan International Airlines, which has owned the property since 2000, leased it in May to the city’s administration for a sum of US$220 million for three years.

More than 116,000 immigrants are estimated to have arrived in New York City since April 2022, when pandemic-related restrictions were lifted. With the curbs gone, those crossing the border illegally could not be kept out for public health reasons and their numbers began to surge.

US laws allow immigrants to stay in the country if they say they are fleeing persecution, while their asylum claims are evaluated and adjudicated. A record-shattering six million encounters – a term that includes both apprehensions and expulsions of people illegally crossing the Mexican border – have been logged at the country’s south-western border with Mexico since President Joe Biden took office.

In August 2023 alone, 232,972 made the attempt, the highest-ever monthly total.

After the sheer numbers of asylum-seekers overwhelmed the small counties in the border states of Texas and Arizona, their governors in 2022 began sending thousands of them on buses to politically liberal cities.

The packed buses to New York City, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Denver and other Democrat-run cities and states were a pointed message to the Biden administration that it should take ownership of the problem.

Though New York has been traditionally welcoming, the sudden influx seems to have touched a nerve, sparking protests across the city, even in areas densely populated by immigrants.

Mr Biden has defended his policies, saying they are grounded in the American values of compassion and fairness. After taking office in 2021, he undid a number of former president Donald Trump’s initiatives that were seen as harsh, including the construction of a wall at the Mexican border and requiring immigrant families to remain in Mexico while their asylum applications were processed in the US.

Last week, the Biden administration gave in to pressure, allowing fast-track construction of new barriers along the southern border resumption of direct deportation flights to Venezuela.

As the crisis plays on, New York City has found itself in the role of an unwitting host under a unique law which decrees it cannot turn away anyone who asks for shelter.

The burden of care has transformed Mr Adams – who called himself the Biden of Brooklyn when he was elected in 2022 – into an aggrieved White House critic. He had initially set up “welcome centres” for the asylum seekers and turned up personally to receive them when the buses first began arriving in midtown Manhattan.

As the costs began to add up, he changed tack. Revealing the figures in August, he said the tab per immigrant household was US$383 a night for food, shelter and medical care for the approximately 60,000 immigrants under the city’s care.

That works up to eye-popping sums:

US$9.8 million a night

US$300 million a month

US$3.6 billion a year

“I have to be honest with New Yorkers with what we’re about to experience: a financial tsunami that I don’t think this city has ever experienced,” Mr Adams said during a town hall meeting with angry New Yorkers in September.

“We are past our breaking point. New Yorkers’ compassion might be limitless, but our resources are not,” he said, repeating his plea for aid from the state and federal authorities.

“This issue will destroy New York City.”

Fleeing a ‘very ugly’ situation

As this writer attempted to enter the Roosevelt, a security guard barred the way. He kept a close watch as I spoke to families milling around the hotel. “No filming,” he shouted when I drew out a camera.

A woman in a black hoodie emerged from the hotel, dragging a pink canvas bag. She agreed to answer a few questions, saying she was waiting for an umbrella so she could step out in the rain and make her way to the laundrette to wash clothes.

Maria gave only her first name, but said she was from Maracaibo, the centre of Venezuela’s oil industry hit hard by the country’s economic collapse. The 37-year-old was living in a room at the hotel with eight members of her family, including her six-month-old baby. Her 13-year-old son, Alexander, shivering a little in his thin T-shirt, stood silently, looking into the distance. “School?” I asked. He shook his head and gazed at his scuffed shoes.

Maria waiting outside the Roosevelt Hotel in midtown Manhattan with her son, Alexander. The pink canvas bag contains soiled clothes that she was waiting to wash at a laundromat nearby.

ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

Speaking in broken English and with the help of a Spanish translation app on her touchscreen phone, Maria said her family had entered the country through the Texas border after a journey of more than 30 days. She said she was fleeing “a very ugly situation” in Venezuela. “There is nothing there. No jobs, no food, no money,” she said, despairingly.

The South American country, on which the US imposed financial sanctions in 2014, is now seeing the world’s largest migrant exodus.

The displacement, bigger in scale than in war-torn Ukraine and Syria, has led to seven million people leaving the country of 29 million. Immigrants reportedly pay drug cartels and human smugglers thousands of dollars to make the long and dangerous journey across the US border.

Maria had been in the United States for less than two months and had not received the coveted work permit that the Biden administration is giving to nearly 500,000 Venezuelans, citing their extraordinary circumstances. But that did not stop her from trying to get a job. She said she had been interviewed at restaurants, so far without success.

Standing a few metres away were a couple with three young daughters in colourful hoodies. The man, who gave his name as Jesus, 35, said he had been making “good money” from his grocery store in Caracas. But when the Venezuelan economy cratered, his business became unviable and he decided his family had a better chance in the US. “I had no good choices left,” he said.

He declined to say if he had paid any gangs to help make the more than 4,000km trip to Eagle Pass, a border town in Texas. He had not obtained a work permit, but had found a job as a construction worker. His daughters, 12, nine and six, watched their father intently as he talked. He said the girls were already picking up a few words of English and would soon enrol in local schools.

At the other entrance to the hotel, barricades stretched over puddles of rainwater and two security vans idled on the sides of the road. Here too, families ventured in and out under the careful watch of security guards, holding hands, distinct in their tentativeness and timidity from the brisk New Yorkers.

The Roosevelt is only one among at least 150 hotels thought to be housing immigrants, with city authorities unwilling to disclose their locations. In the Chelsea neighbourhood of Manhattan, a hotel manager said he had turned down the city authorities’ request to house illegal immigrants. They would have occupied two floors that had been used during the Covid-19 pandemic to hold families serving quarantine.

“It’s not good for business,” the manager said.

When the city ran out of space to house the migrants, officials requisitioned vacant buildings, gyms, churches and even a cruise ship terminal. There are also plans to utilise disused hangars at the city’s first airport, the Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn. Up to 2,500 male migrants are to be housed at the 12.1ha site leased by the city for US$1.7 million a month.

New York City’s first airport, Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, could house up to 2,500 male migrants if plans by the authorities go through.

ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

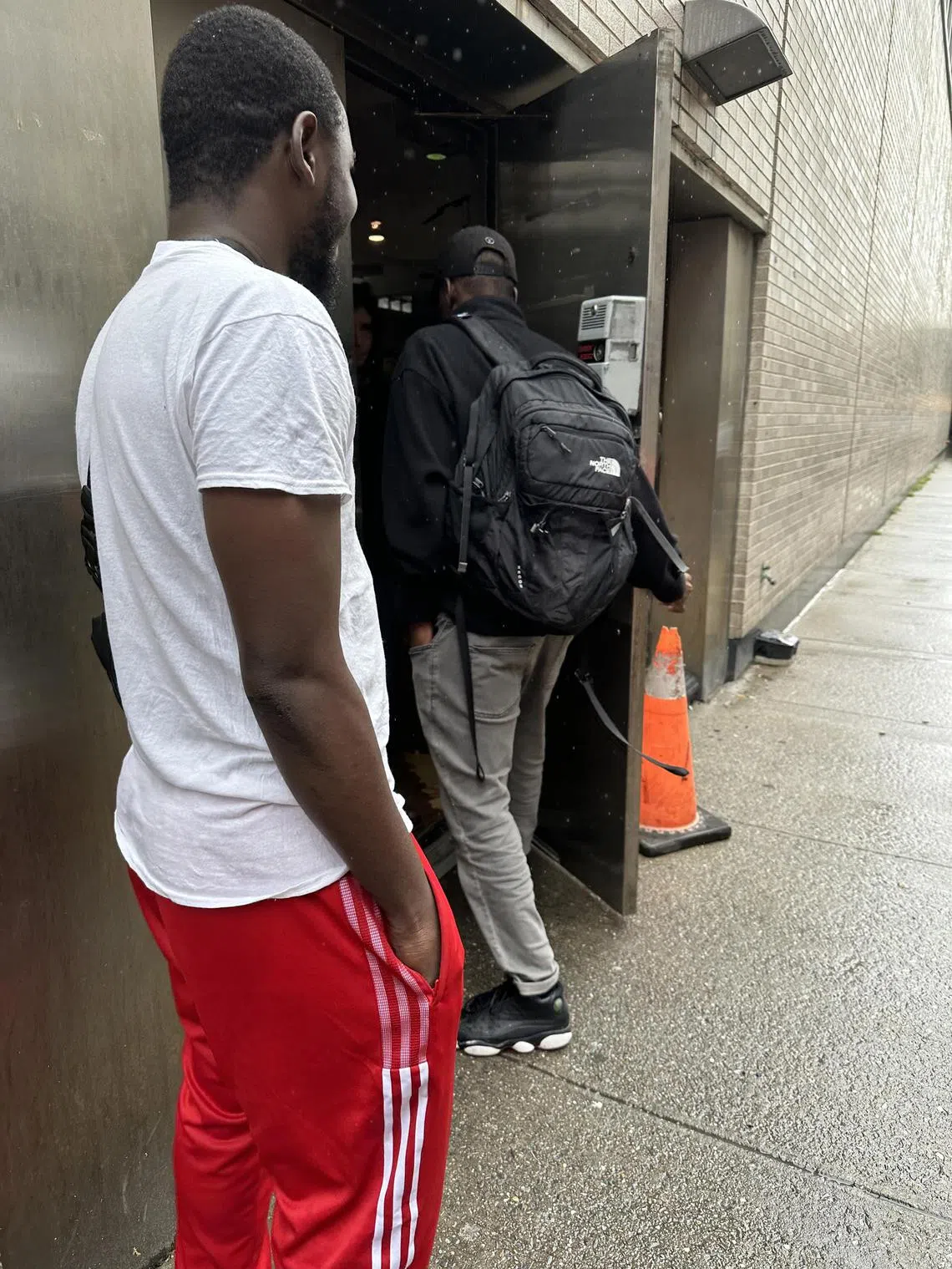

About 15km away from the Roosevelt, the former New York Police Academy in the Gramercy Park neighbourhood is also a shelter. The nine-storey building is no longer used to train policemen but still serves as a recruitment centre. A sentry, shrugging, pointed out the entrance used by the migrants.

Two young men emerged from the metal doors, revealing a glimpse of a large room resembling a dormitory, with beds lined up along its entire length. The migrants housed here move freely within the city.

Refusing to give their names, the men said they were from Conakry, Guinea. They had flown to Mexico City, slipped across the border and made their way to New York after spending a month in California and 40 days in Philadelphia.

“No work papers,” they said when asked if they had managed to find jobs. They might not have a roof for too long either, after the mayor served notice that adult migrants without children must vacate shelters in 60 days in accordance with city rules. They might have to move to other shelters or find their way to another city.

Two men from Conakry, the capital of the West African nation of Guinea, who said they were sheltering at the old New York Police Academy. Without work permits, they are unable to find jobs.

ST PHOTO: BHAGYASHREE GAREKAR

Mr Adams is practising his Spanish these days, and went on a trip to Central and South America recently to convince migrants not to come to the Big Apple.

A former police officer himself, he has distributed fliers at the southern border warning asylum seekers that there is “no guarantee” they will receive shelter or services.

“Housing in NYC is very expensive,” the fliers say. “Please consider another city as you make your decision about where to settle in the US.”

The city has also rerouted migrants to other counties in New York state, angering their local officials. At the same time, the city is trying to limit the scope of its right-to-shelter law, arguing that it was designed to address the local homeless problem, not illegal immigrants.

Jobs are ‘plentiful’

Not all New Yorkers view the new arrivals as a nuisance. Mr Gherezghiher Hailu, a taxi driver who arrived from Eritrea more than 30 years ago, fleeing war there, said giving migrants refuge was the humane thing to do – and also very American.

The US is home to more international migrants than any other country. It has more than the next four countries with the biggest migrant populations – Germany, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Britain – combined, according to the United Nations’ 2020 data. While the US population accounts for about 5 per cent of the world population, close to 20 per cent of all global migrants live in the US.

Immigrants are credited with invigorating the economy, accounting for one in six workers and creating about one in four of new businesses.

Officials say there are thousands of unfilled vacancies in the restaurant and hospitality industry in New York City, and farm jobs upstate. “I have hundreds of employers all across this state who’d love the opportunity to hire these individuals, train them first, hire them, and bring them into the legal economy because they are sliding into the illegal economy now,” New York Governor Kathy Hochul recently said.

Mr Hailu agreed. “The city needs workers. The newcomers eagerly take on jobs that New Yorkers don’t care for. And employers can get away paying them half the minimum wage of US$16 an hour,” he said.

“But I did not cross into the US illegally,” he added, in a refrain often heard about the new influx. Caught in Eritrea’s long war with Ethiopia, which set off a civil war, Mr Hailu fled to neighbouring Sudan. From its capital, Khartoum, he applied for asylum in 1982 and was evacuated to New York. He says he has since paid back the US$600 airfare to the US government.

His family of four has lived the American dream; he has made it in New York, New York.

It is the same journey that the new migrants are being given the chance to make. But the welcome is wearing thin. Fewer may be able to live out the lyrics from Frank Sinatra’s 1979 hit that became New York’s unofficial anthem:

If I can make it there

I’ll make it

Anywhere

It’s up to you

New York, New York

I want to wake up in a city

That never sleeps