UN road map seeks to crack $1.7 trillion climate finance puzzle

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

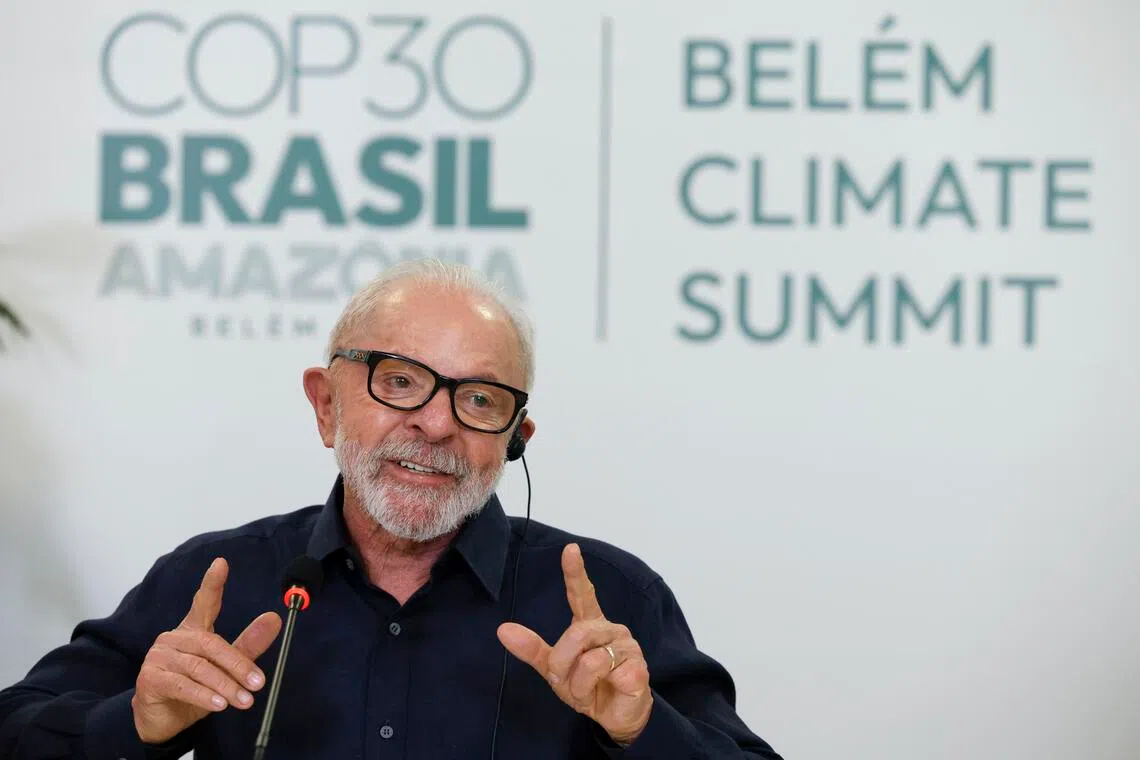

Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva speaking at an interview ahead of the COP30 climate summit in Belem, Brazil, on Nov 4.

PHOTO: EPA

Follow topic:

- A UN report calls for a dramatic increase in climate finance, aiming for US$1.3 trillion annually by 2035 for poorer nations, ahead of COP30 in Brazil.

- The "Baku to Belem roadmap" suggests using public, private and innovative finance sources to spur investment in renewable energy and adaptation measures.

- The plan outlines five action areas, including replenishing funds, rebalancing debt, rechanneling private finance, revamping capacity, and reshaping regulations.

AI generated

SINGAPORE - A United Nations report on Nov 6 sketches out a plan to dramatically scale up climate cash to US$1.3 trillion (S$1.7 trillion) a year for poorer nations to help them green their economies and adapt to the worsening ravages of a hotter world.

The road map comes just days before the Nov 10 to 21 COP30 UN climate conference in Belem, Brazil. It pieces together the puzzle of different sources of finance to accelerate investment in renewable energy and the switch to cleaner industries, cut debt and dramatically boost money for adaptation to rising heat, floods and rising sea levels.

“For the first time, more than 200 governments, banks, businesses and communities have joined forces to outline workable solutions for mobilising climate finance,” UN climate change executive secretary Simon Stiell said in a statement.

Scaling up climate finance can bring tremendous benefits for the global economy – generating jobs, protecting communities and driving innovation, he said.

“The task is ambitious, but achievable. The tools exist; what’s been missing is coordination and shared commitment,” he added.

The issue of climate finance for poorer nations has bedevilled UN climate talks for years because wealthier nations have long dragged their feet on coughing up climate cash. This is despite rich nations being historically the largest emitters of greenhouse gases that are heating up the planet.

Climate finance has become increasingly urgent. More than half of the world’s population live in developing nations, and the climate impacts affecting them are growing ever larger. Developing nations, including China, are now the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions because of their deep dependency on polluting fossil fuels. So there is a need for climate cash not only to help them cope with climate change but also to shift away from coal, oil and gas as fast as possible.

On Nov 4, the UN Environment Programme said the world is set to blow past the 1.5 deg C Paris Agreement temperature guardrail

At the COP29 talks in Baku, Azerbaijan, in 2024, a decision was made for the presidencies of COP29 and COP30 to come up with a plan to greatly lift annual climate finance from the US$300 billion agreed in Baku

Not an easy challenge since many nations, rich and poor, are cash-strapped and indebted.

The plan, called the Baku to Belem road map to 1.3T, shows that reaching US$1.3 trillion by 2035 will require a mix of public, private and innovative sources of finance.

This will include concessional capital, which is funding offered on more favourable terms than market rates, funding from philanthropy – which can help de-risk early-stage green investments – and perhaps a variety of new taxes.

But the gap remains large. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, developed countries provided and mobilised US$115.9 billion in climate finance for developing countries in 2022.

Yet the opportunities are also significant. Asia faces a shortfall of at least US$800 billion annually in climate financing, Singapore’s Ambassador for Climate Action Ravi Menon said on Sept 9.

Fast-growing South-east Asia, with nearly 700 million people and expanding energy needs, is hungry for investment. And blended finance, mixing public, private and philanthropic funding to lower the cost of capital, can help bridge the funding gap.

Fast-P – a blended finance initiative by the Monetary Authority of Singapore – aims to help finance Asia’s decarbonisation, with the target of eventually raising up to US$5 billion. It recently raised US$510 million

The UN report draws on views in 227 submissions from non-governmental groups, business, research groups, cities, academia and others.

The authors note that achieving climate and sustainable development goals will require every actor, such as governments, multilateral development banks and funds, investors, the financial system and civil society, to start working together to mobilise against climate change, rather than working in a piecemeal fashion.

The report recommends five action fronts on finance:

Replenishing: Boosting grants, concessional finance and low-cost capital. For example, multilateral climate funds should be replenished with greater amounts of money and with a greater emphasis on early-stage innovative financial instruments and structures that de-risk climate investments.

Rebalancing: Giving poorer nations financial breathing room. For instance, alleviating debt burdens through debt-for-nature/climate swaps. Debt-for-climate swaps mean a country’s debt is reduced or refinanced in exchange for a commitment to invest the savings in climate-related projects.

Rechannelling: Ramping up private finance and affordable cost of capital. Governments cannot do all the heavy financial lifting. Much of the money will need to come from private sources that can help de-risk investments, especially in poorer nations with governance concerns. Private money, when blended with public and philanthropic finance, can lower the cost of capital, and act in a “catalytic” way that draws in more investors and helps new technologies to scale.

Revamping: Developing nations need assistance to boost their capacity to conceive, manage and monitor climate investments that align with their development goals. This requires coordination between a number of ministries that might also need capacity building, in terms of finance and training and policy development. “Climate action has too often been treated as external commitments, disconnected from national economic planning,” the authors say.

Reshaping: Rewiring the global financial regulatory system is needed to enhance investment flows into climate projects in developing countries. Many rules and norms related to how investment risks in developing countries are perceived in the financial system can create barriers to the flow of climate finance. Several aspects of regulatory standards or information sources may overstate the risk of investing in developing countries or may inadvertently disincentivise cross-border investment, the authors say.

The report makes more than two dozen recommendations for these five areas.

It also says investments should be framed around a number of themes, such as adaptation and boosting climate resilience; improving access to clean energy; investments that reward conservation and promote restoration of forests, oceans and mountain ecosystems; and supporting agriculture and food systems.

There are a variety of ways to raise climate cash.

For example, direct budget contributions could come from overseas development assistance. Redirecting and new issuances of special drawing rights (SDR) – an international reserve asset created by the International Monetary Fund – could potentially raise US$100 billion to US$500 billion per year.

The SDR is not a currency but an asset that holders can exchange for currency when needed. Its value is based on a basket of five currencies – the US dollar, the euro, the Chinese renminbi, the yen, and the British pound sterling. Individuals and private entities cannot hold SDRs. Only IMF members and others, such as central banks, can hold them.

Carbon pricing could raise anything from US$20 billion to US$4.9 trillion, depending on the rate applied and participating economic actors and areas.

Fees on aviation and maritime transport and taxes on luxury fashion or other goods could raise billions more. Taxes could also be applied to financial transactions and on wealth. For example, wealth taxes could raise between US$200 billion and US$1.36 trillion, depending on the rate applied at different income thresholds.

And there are other sources of money, too: The UN estimates that in 2023, fossil fuel subsidies, such as tax breaks and artificially low fuel prices, totalled US$1.1 trillion. And the UN estimates that US$470 billion a year is spent on agriculture subsidies that are harmful to people and the planet.

The good news is that for climate finance, there are hopeful signs. Renewable energy and electric vehicle investments have soared globally as costs have plunged and investors are increasingly looking at opportunities in South-east Asia, Ms Kyung-Ah Park, chief sustainability officer for Singapore investment firm Temasek, told the Straits Times’ Green Pulse podcast

As a long-term investor, the clean energy and transition agendas are a “must do”, she says. It is just good business and a lot of investors are staying the course.

Reactions to the road map have been mixed, and how it will be included in any final set of decisions from the COP30 conference is a key aspect.

“The action-oriented elements of the proposed roadmap are to be welcomed. But the main issue is a massive shortfall in climate finance that must be urgently addressed to support scaled-up climate action within this decade and in order to limit likely warming overshoot as close as possible to 1.5 deg C,” Dr Bill Hare, chief executive of Climate Analytics, a Berlin-based climate science and policy think-tank, told The Straits Times.

“All the governments attending the COP will have to decide how to take the report’s recommendations, but it’s not clear how that’s going to actually happen at this stage,” he added.

Mrs Melanie Robinson, Global Director of Climate, Economics and Finance at the World Resources Institute think-tank, said in a statement: “For too long, the climate community has been overly focused on relatively modest sums of public climate funding, whereas the Baku to Belem plan rightly shifts the lens to how a wider set of public finance and policy shifts can unlock much larger flows from private investors.”