UN climate chief renews plea for countries to plan for climate change impact

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The remarks come as the Philippines was ravaged by its sixth tropical storm in less than a month.

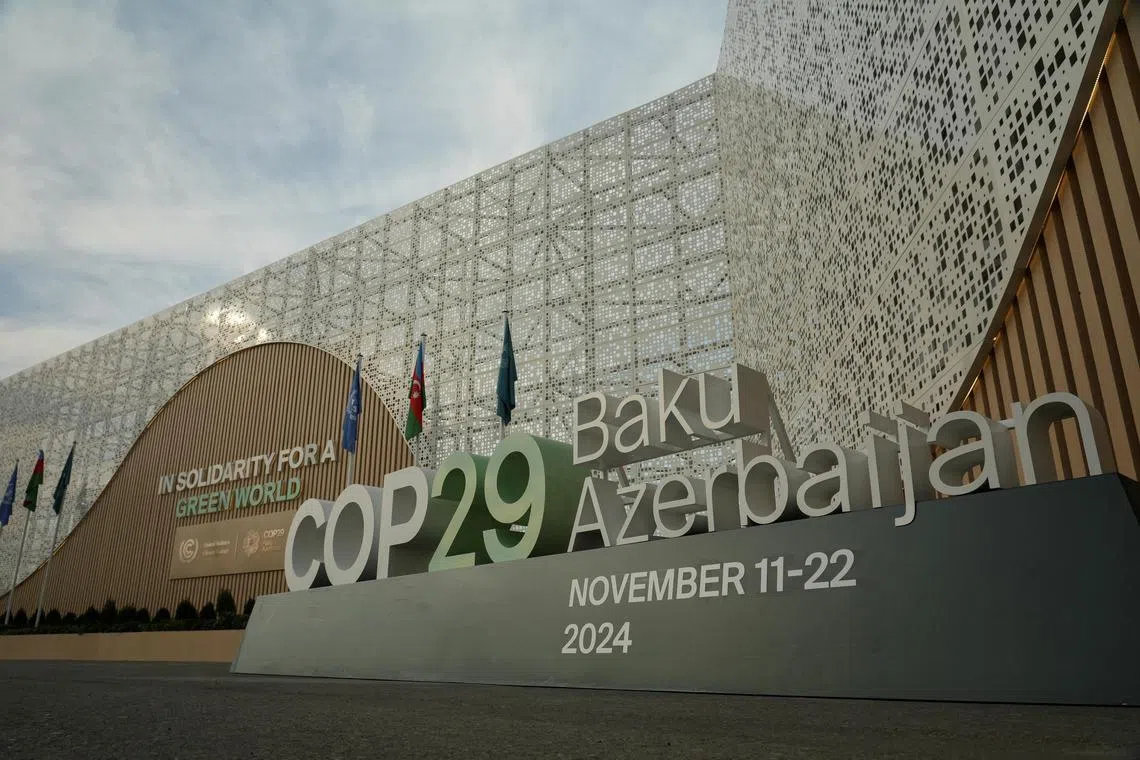

PHOTO: REUTERS

BAKU, Azerbaijan – Every bit of preparation against climate change impacts makes the difference between life and death for millions of people around the world, UN climate chief Simon Stiell stressed.

His remarks at the UN climate change summit (COP29) in Azerbaijan on Nov 18 come as the Philippines was ravaged by its sixth tropical storm in less than a month.

Super Typhoon Man-yi slammed into highly-populated Luzon on Nov 17,

Speaking at a high-level event on climate adaptation, Mr Stiell noted that nearly half of the human population live in climate vulnerability hotspots, where people are 15 times more likely to die from climate impacts.

“Personally, I find this deeply disturbing, highly offensive,” he said.

Even as he made a renewed plea for countries – especially the most vulnerable ones – to start planning for climate change, Mr Stiell called for more innovative financing to channel money to countries that need to build resilience against climate impacts.

“We can no longer rely on small streams of finance. We need torrents of funding. They need to be easier to access, especially for the most vulnerable countries that often face the biggest barriers,” he said.

Countries previously agreed to have their national adaptation plans ready by 2025, to be implemented by 2030.

Such plans lay out a country’s medium- and long-term solutions to limit the impact of climate change on communities.

To date, 60 countries – mostly developing or least developed nations – have submitted their national plans. South-east Asian countries on the list include Cambodia, Thailand, Timor-Leste and the Philippines.

Singapore’s adaptation efforts are included in its climate targets document, which was last updated in 2022 and submitted to the UN. It outlines the island-state’s efforts to protect its coastlines against sea level rise, which are estimated to cost $100 billion over 100 years, among other measures such as strengthening food security and having biodiversity conservation programmes in place.

Countries’ adaptation costs could rise to US$340 billion (S$456 billion) per year by 2030, reaching as much as US$565 billion per year by 2050, Mr Stiell noted.

“The funding exists. We need to unlock and unblock it.”

He urged multilateral development banks to think beyond traditional grants and loans, and philanthropies, the private sector, and bilateral donors to step up without increasing the debt faced by vulnerable countries.

“The people who receive this investment will not disappoint. They want to adapt. Often, they know better than we do just how to adapt,” he added.

Mr Stiell noted that nearly half of the human population live in climate vulnerability hotspots.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Adaptation outcomes at COP29 are expected to be closely linked to a new climate finance goal, which will be the summit’s primary outcome and define the success of the talks.

Developing countries are calling for developed nations to commit to US$1.3 trillion per year to help the more vulnerable countries meet their climate targets and adapt to disasters that disproportionately fall on them.

In its adaptation gap report published in early November, the United Nations Environment Programme found that public finance to help vulnerable countries adapt to climate impacts increased from US$22 billion in 2021 to US$28 billion in 2022.

But this amount still leaves a huge adaptation finance gap, estimated at between US$187 billion and US$359 billion per year.

Furthermore, a lack of transparency and accessibility of some countries’ climate risks would make the financial system more vulnerable and also hinder access to capital for climate adaptation, said Singapore-based Anjali Viswamohanan, who spoke at the meeting.

This was a problem highlighted in an analysis of adaptation policies of several Asian and Asean markets including China, India and Malaysia published by the Asia Investor Group on Climate Change (AIGCC) in November.

Ms Viswamohanan, director of policy at AIGCC, cited a survey that found that 49 of 52 the world’s largest institutional investors – managing roughly US$50.2 trillion in Asia – have policies on climate risks and opportunities.

“This means that a large number of financial institutions understand that climate risk is a financial risk and would be keen to see clear plans from policymakers to address these risks that private capital can contribute to,” she told ST.

“(But) if there is a misalignment (between the private sector and country) of what the risks are, you’re not going to align on the type of financing, the type of projects that’s required... you will not actually get projects that are investable.”

Neighbouring countries also need to consider transboundary climate impacts such as air pollution or haze, and water shortage from a drought, she noted.

“But several countries are not adequately thinking about or coordinating on these risks. We found very little concrete information on that in their adaptation plans,” she added.

Beyond having a national plan in place, the local communities need to be the ones leading the projects, since every island or province faces differing climate impacts, noted Ms Maheen Khan, an international climate resilience adviser at WWF-Netherlands. She was speaking at a press conference by the World Wide Fund for Nature on the morning of Nov 18 at the summit.

“Adaptation is local. So adaptation in Siargao in the Philippines will differ from that in Palawan,” she said. “We have to cater to the adaptation needs and risks of the local community, the village that we want to have a solution.”