N2O, the forgotten greenhouse gas, is rising quickly and adding to climate fears: Study

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The use of fertilisers is a major source of nitrous oxide emissions from human activity.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

SINGAPORE – One of the most potent greenhouse gases, nitrous oxide (N2O), is increasing in the atmosphere at an alarming rate, putting at risk efforts to limit global warming, a major study said on June 12.

Most people might know of N2O as laughing gas used in the dentist’s chair or as a fuel used in drag racing. Its climate role is less well known and one of its main sources from human activity is food production – mainly the growing use of nitrogen-based fertilisers and animal manure for crops.

The peer-reviewed assessment, called Global Nitrous Oxide Budget 2024, is the most comprehensive study yet of N2O sources and natural sinks, involving 58 scientists in 15 countries. The study was published in the Earth System Science Data journal.

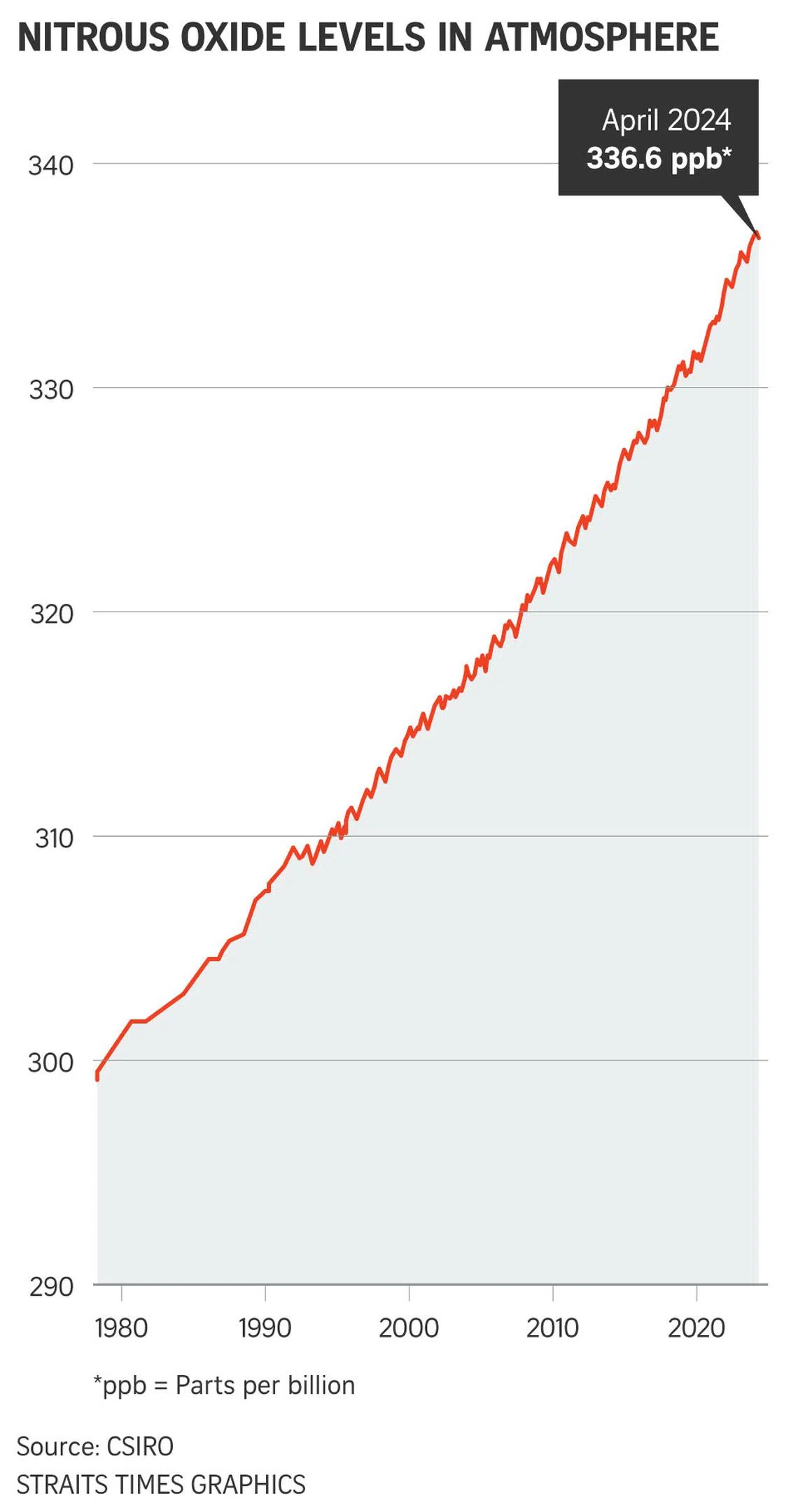

N2O emissions have risen by 40 per cent between 1980 and 2020. The authors found that growth rates over the 2020-2022 period were higher than any previous observed year since 1980 when reliable measurements began.

Scientists are concerned because N2O, which lingers in the atmosphere for as long as 117 years, is 273 times more potent as a greenhouse gas compared with carbon dioxide (CO2) over a time horizon of 100 years.

It is the third-largest contributor to global warming after CO2 and methane, and failure to check the continued rise in emissions will add to the global struggle to tackle climate change.

This is because methane emissions from human activities are rising. CO2, whose annual emissions have largely flatlined, is not on track for a steep decline by 2030, which the UN’s climate science panel said is needed to limit global warming to 1.5 deg C above pre-industrial levels. Based on current climate policies, the planet is on track to warm about 3 deg C by the end of the century.

“If we are to stabilise the climate, at any temperature, let alone below 2 deg C, we must bring down emissions of all greenhouse gases,” said Dr Pep Canadell, executive director of the Global Carbon Project, an international scientific consortium that carried out the assessment.

“N2O doesn’t necessarily need to go to zero to stabilise the climate – as CO2 needs to – but continued growth in N2O emissions is taking us in the wrong direction.”

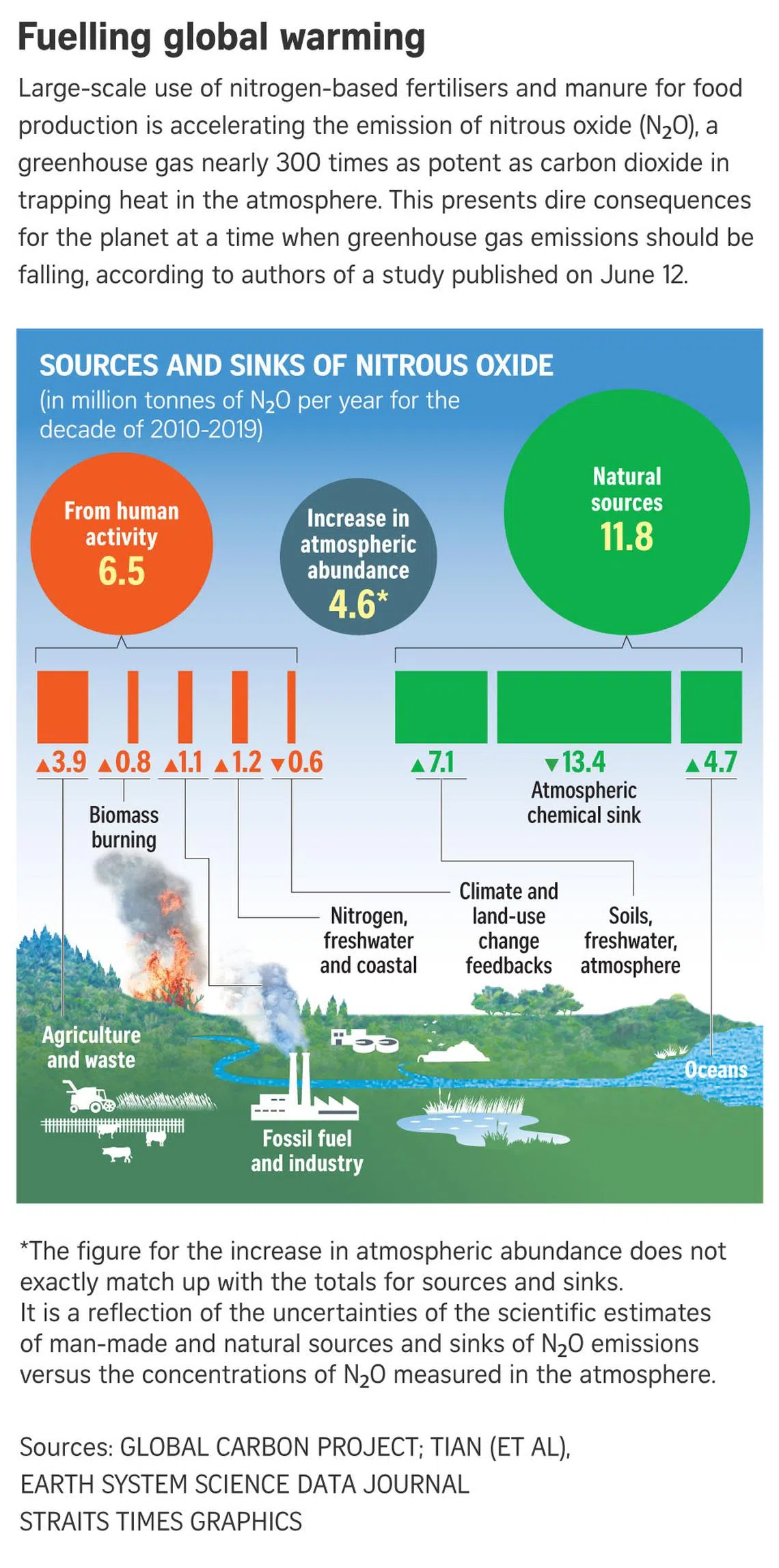

The authors looked at all the major global sources of N2O from human activities and nature.

They found that observed atmospheric N2O concentrations in the decade 2010 to 2019 were increasing faster than the pessimistic greenhouse gas trajectories used by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Those trajectories would lead to global mean temperatures rising by more than 3 deg C by 2100.

Agricultural production contributed 74 per cent of the total N2O emissions from human activities in the 2010-2019 decade. Contribution from other sources, such as fossil fuels and the chemical industry, is stable though not declining, the study noted.

Nature remains a major source. N2O is produced by microbes in soils and fresh water, as well as oceans. But the gas is removed from the atmosphere naturally when it is absorbed by bacteria or destroyed by ultraviolet radiation or chemical reactions.

The problem is that human activities are producing far more N2O than nature can handle. This results in the gas accumulating in the atmosphere.

The top five emitters by volume of N2O linked to human activities in 2020 were China (16.7 per cent), India (10.9 per cent), the US (5.7 per cent), Brazil (5.3 per cent) and Russia (4.6 per cent). This was the year with the most recent complete data. Globally, farmers used 60 million tonnes of nitrogen fertilisers in 1980, rising to 107 million tonnes by 2020. In 2020, farmers also used 101 million tonnes of manure to fertilise crops. Manure, like nitrogen fertilisers, also releases N2O.

N2O emissions from China, India and Brazil have more than doubled relative to 1980. And developing countries in Africa as well as South and South-east Asia also show a significant increase in fertiliser use.

“Increased efficiency in the use of nitrogen fertiliser is the very first step and it is an easy win-win,” said Dr Canadell. “This saves on fertiliser cost, reduces water pollution and cuts ozone-depleting gases.”

Crops take up only between 30 per cent and 50 per cent of the nitrogen they get from fertilisers. Much of the fertiliser runs off into waterways, or gets broken down by microbes in the soil, releasing N2O into the air.

Using the right amount of fertiliser and application at the right time and the right soil depth are ways to improve efficiency. Genetic engineering of some crops can also cut down the need for nitrogen fertilisers, while planting alternate crops with legumes, which fix nitrogen from the atmosphere and enrich the soil, is another solution, Dr Canadell noted.

Reducing meat consumption would also reduce N2O emissions through less manure and less need for fertiliser for fodder, he added.

“Overall, N2O emissions have not had the attention, investment and innovation that we have seen for carbon dioxide and methane mitigation,” he said.

Polluted waterways, drinking water and coastal zones have been the main reasons for countries to reduce excessive use of fertilisers and manure. And yet, in addition to the planet-warming properties of the gas, N2O is also damaging the earth’s protective ozone layer.

“These are all powerful reasons to regulate nitrogen,” Dr Canadell said. “If we were to count the economic costs of all these impacts, reducing N2O emissions would be one of the most cost-effective environmental policies in the world.”