Maduro ouster leaves Cuba’s wobbling regime without a benefactor

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

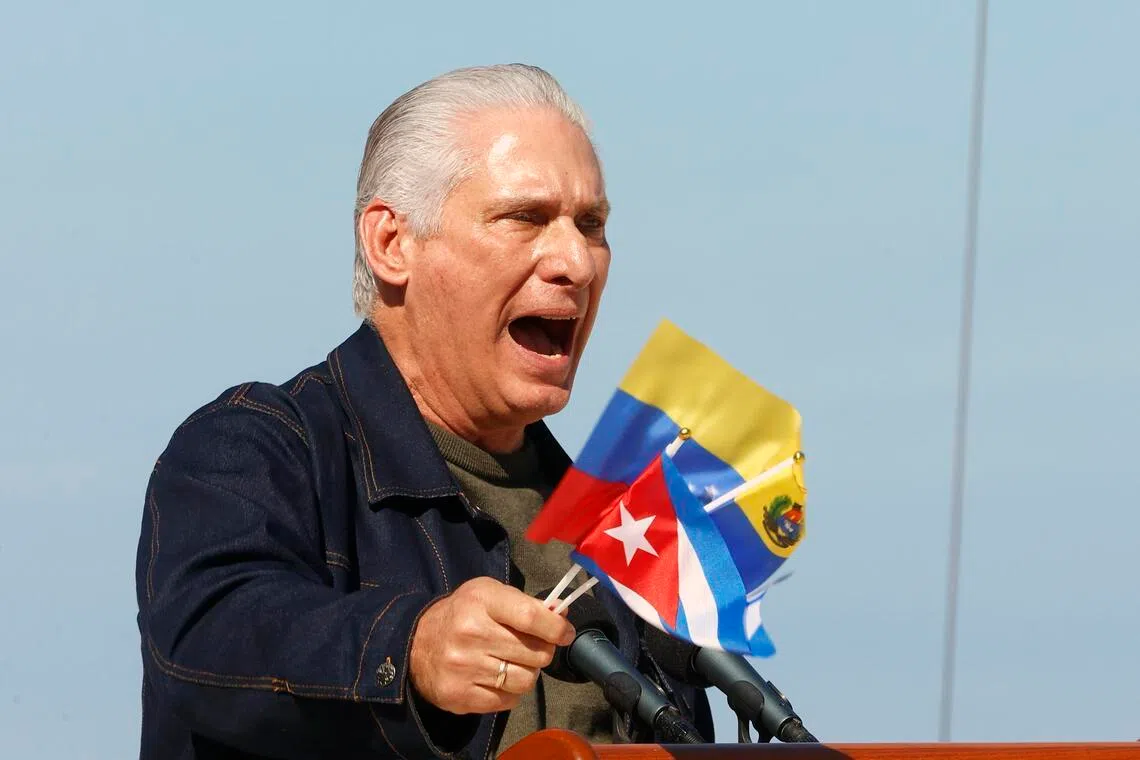

Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel speaking during an event held in support of Venezuela in Havana on Jan 3.

PHOTO: EPA

HAVANA - Hours after the US military whisked Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro away

With Mr Maduro now awaiting trial in New York,

For decades, Venezuela provided the communist-run island with the bulk of its fuel and financing in exchange for Cuban doctors, teachers and security personnel. Without those programmes, the island’s already devastating energy woes will worsen and its shortages of food, medicine and basic goods will become even more pronounced.

“They’ve been left without a godfather, a benefactor that has been paying their bills, and they’re totally bankrupt,” said Mr Emilio Morales, president of the Miami-based Havana Consulting Group. “How are they going to survive?”

During a meeting of Cuba’s legislature in December, officials painted a grim economic picture as they placed blame for the current crisis on long-running US sanctions. But declining shipments of Venezuelan crude are also a factor.

Cuba needs approximately 100,000 barrels of oil per day to function but produces just two-fifths of that, according Mr Jorge Pinon, a researcher at the University of Texas Energy Institute who tracks fuel shipments to the island. A decade ago, Venezuela provided enough to fully meet Cuban demand. But by Mr Pinon’s last count, Caracas was sending just 35,000 barrels a day before US President Donald Trump’s administration started seizing oil tankers in December.

The lack of fuel is leading to massive, economy-crushing blackouts in Cuba. Agricultural production and tourism to the island are also at their lowest levels in decades. More than two million people – about a fifth of the island’s inhabitants – do not have reliable drinking water.

As a result of the crisis, Cuba’s population has collapsed 15 per cent over the last decade. The government expects to lose another 20 per cent of its people by 2050. The signs of strain are everywhere, from garbage going uncollected to empty shelves and soaring rates of mosquito-borne disease in a nation that used to hold up its health sector as a global model.

On Jan 3, Mr Trump suggested the regime in Havana was so weak that military force would not be needed to usher in change. “Cuba is going to fall of its own volition,” the US President told the New York Post.

Led by Secretary of State Marco Rubio – born in Florida to Cuban parents – Washington has nonetheless been ratcheting up pressure on Havana. Speaking alongside Mr Trump on Jan 3, Mr Rubio said Cuba’s leaders should be “concerned” by Mr Maduro’s removal.

“The Cuban government is a huge problem,” Mr Rubio said on Jan 4 on NBC’s Meet The Press programme. Though he declined to indicate whether the US would target Havana next, he added: “I don’t think it’s any mystery that we are not big fans of the Cuban regime who, by the way, are the ones that were propping up Maduro.”

Key to Washington’s strategy will be keeping other nations from filling the Venezuelan funding gap. While Mexico, Russia and Iran have, at times, provided Cuba with fuel, it has not been enough to keep the economy running.

Mexico shipments dwindled to about 7,000 barrels a day in 2025, according to Mr Pinon, down from as much as 22,000 barrels in 2024. In addition to having to negotiate security and trade issues with Mr Trump, Mexico President Claudia Sheinbaum is facing domestic pressure to be more transparent about her government’s energy shipments to Cuba.

Mr Diaz-Canel has “no allies in the hemisphere that will risk what are already fragile ties with Washington over Cuba”, said Mr Ricardo Herrero, executive director of the Cuba Study Group, citing Mexico, Brazil and Colombia. “And it’s hard to imagine Russia, China or anyone else will come to the rescue.”

Even if Cuba can find a fuel supplier, it is unlikely to receive the same sweetheart deals that Caracas provided. Any new saviour would have to take on Cuba as a credit risk and Washington as a political foe. “It appears Cuba has no options,” Mr Herrero said. “Their economy will be pulverised.”

To be sure, the Cuban regime has shown remarkable tenacity in the past, prompting some analysts to caution against seeing Venezuela as a make-or-break ally. “In theory, there are other solutions that Cuba could pursue with other partners around the world that would compensate for Venezuela to some degree,” said Mr Andres Pertierra, a Cuban-American historian who lived on the island for much of 2024 and is completing a dissertation on regime durability.

Mr Pinon, however, cannot think of any other nation willing to barter with the Cubans for fuel. So he wonders if the US, despite Mr Rubio’s bellicosity, will allow Venezuela to keep supplying oil in the short term. “Nobody wants a failed Cuban state,” he said.

It is also unknown how a post-Maduro government in Caracas will treat Cuba. Mr Trump has said Venezuela’s Vice-President Delcy Rodriguez is now in charge, and though she is a staunch ally of the ousted socialist leader, she is not viewed as being as sympathetic to the regime in Havana as her predecessor.

Should ties be completely severed, it is hard to quantify the damage that will done to Cuba’s leadership, according to Mr Morales.

“It’s not just the lack of fuel, but the lack of money, their loss of influence, their loss of control over third parties,” the Havana Consulting Group president said. “They’ve never suffered a blow like this. It’s devastating.”

Though Cuba has long defied the odds – surviving multiple US attempts to kill or oust its leadership since the 1959 revolution, plus weathering a decade of pain after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1980s – the path ahead is becoming increasingly narrow.

The island “is in its darkest period in the last 65 years”, Mr Herrero said. “There’s no telling how it will come out on the other end.” BLOOMBERG