Why Ukraine’s Donbas region matters to Putin

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

A Ukrainian soldier scanning the horizon for Russian military from his position in the southern Donbas region in Ukraine, Nov 29, 2022.

PHOTO: REUTERS

KYIV – The two eastern provinces of Ukraine known collectively as the Donbas have emerged as the main battlefield for Europe’s biggest armed conflict since World War II.

The region was already central to Russia’s strategy for asserting influence over its neighbour since 2014, when Moscow fomented an armed insurgency there.

In February, Russian President Vladimir Putin declared the provinces independent,

In late September, he took things further, announcing Russia’s annexation of both provinces, together with two others,

Why is Putin so focused on Ukraine?

Since at least 2007, Mr Putin has repeatedly lamented Moscow’s diminished role in the world following the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, which had included Ukraine.

He has since tried to carve out a sphere of influence for Moscow in the former Soviet space, pushing back against efforts by Ukraine and Russia’s other neighbours to join or associate with institutions such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the European Union.

He tried to build Russian-led equivalents – the Collective Security Treaty Organisation and the Eurasian Economic Union – but without Ukraine, a fellow Slavic nation of 44 million people, their potential was limited.

What’s Russia’s history with the Donbas?

The areas of Ukraine now covered by Donetsk and Luhansk provinces came under the control of the Russian Empire in the mid-18th century, soon after the discovery of coal there.

The coal turned the region into Ukraine’s industrial heartland and attracted Russian settlers.

With ties to Russia still stronger than in most other parts of Ukraine, the Donbas more recently was a bedrock of support for the Donetsk-born Viktor Yanukovych, who became Ukraine’s president in 2010.

Mr Yanukovych was toppled in 2014 by street protests over his decision – made under pressure from Moscow – to renege on signing a trade pact with the EU.

What led up to the war?

Following Mr Yanukovych’s removal, which Russia portrayed as a Western-backed coup, Mr Putin sent troops wearing no insignia to seize Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula, where a majority of the population identified as ethnic Russian in the last census in 2001.

The operation faced minimal armed opposition.

Elsewhere in Ukraine’s east and south, where 14 per cent to 39 per cent identified as ethnic Russian, critics of the new pro-Western government tried to emulate that success with the backing of Russian agents, taking control of some cities and declaring breakaway republics in Donetsk and Luhansk.

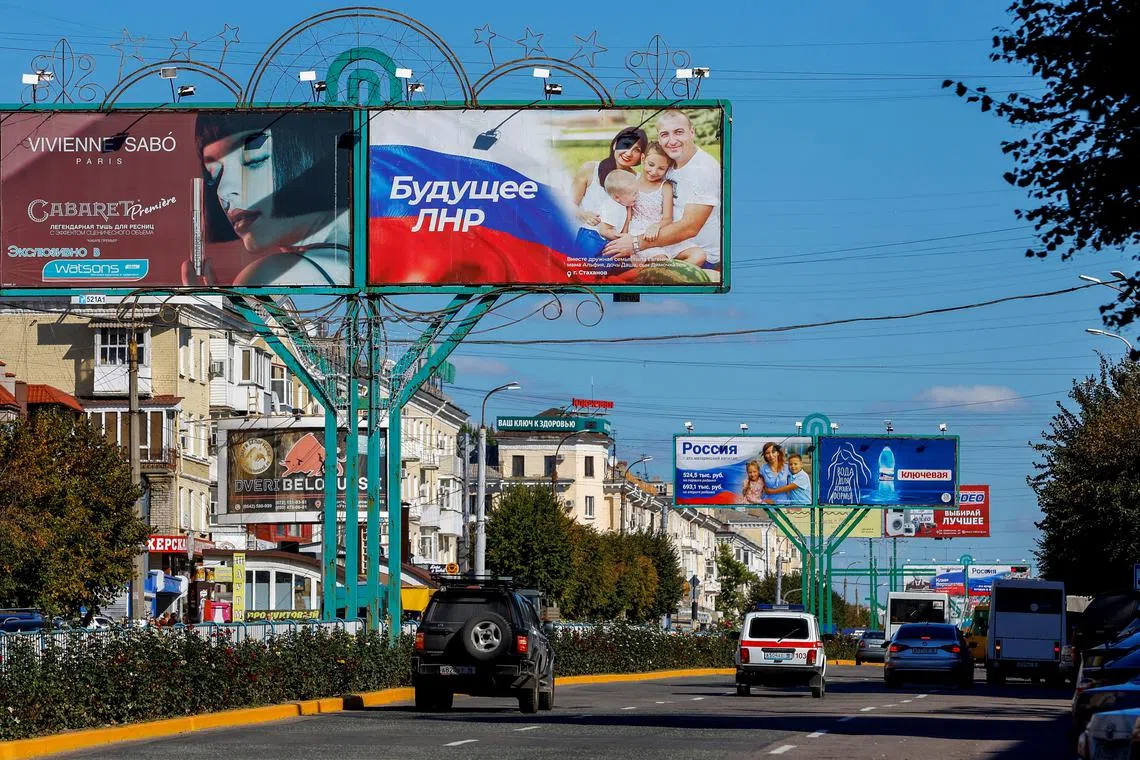

Pro-Russian signboards are seen along a street amid the Russia-Ukraine conflict in Luhansk, Ukraine, on Sept 20, 2022.

PHOTO: REUTERS

But this time there was resistance. Clashes broke out and an armed conflict developed in the Donbas that dragged on for eight years, despite the signing of two peace agreements.

Russia saw the terms of the accords as federalising Ukraine, creating wide autonomy for the Donbas so as to make it impossible for the country to join Nato or the EU.

When the agreements weren’t implemented in that way, Russian officials grew frustrated.

How did the war unfold?

Originally, Russia launched a multi-front assault on Ukraine, moving on major cities including the capital, Kyiv.

But after a month of fighting, Moscow appeared to redefine its war aims in the face of stiff Ukrainian resistance.

It pulled forces from the north to concentrate on securing all of the Donbas

With the fall of Mariupol,

Yet the campaign to drive Ukrainian forces from the Donbas ground to a halt by mid-summer.

After a string of humiliating military reversals, Russia organised sham status referendums across the areas it still controlled, and on Sept 30 declared that Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia were now part of Russia.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has pledged to take back all of the country’s territory,