Ukraine struggles to identify thousands of soldiers’ remains as relatives ache for news

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Relatives of missing service members attending a rally in Kyiv, Ukraine, on Oct 16, 2024.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Follow topic:

KYIV - It has been more than a year since Ms Anastasiia Tsvietkova’s husband went missing fighting the Russians near the eastern city of Pokrovsk, and she does not know whether he is alive or dead.

Russia does not routinely provide information about those captured or killed, and there has been no news from fellow soldiers or the International Red Cross, which can sometimes visit prisoner-of-war camps.

If Mr Yaroslav Kachemasov was indeed killed on the front, then the recent repatriation of thousands of bodies might at least allow Ms Tsvietkova to grieve.

Yet even that still seems a remote prospect, as Ukraine’s forensic identification laboratories are overwhelmed by not only the sudden arrival of so many bodies, but also the difficulty of identifying remains that may be burned or dismembered.

Tracing Ukraine’s war dead: DNA and detective work

The 29-year-old dentist living in Kyiv submitted a sample of her husband’s DNA, filled in dozens of forms, wrote letters and joined social media groups as she sought information.

Mr Kachemasov, 37, went missing during his second combat mission near Pokrovsk, which Russia has been attacking for months. The place where he disappeared is now occupied by Russia.

“The uncertainty has been the toughest,” Ms Tsvietkova told Reuters. “Your loved one, with whom you have been together day in, day out for 11 years – now there is such an information vacuum that you simply don’t know anything at all.”

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022

In the last four months, more than 7,000 mostly unidentified bodies have been brought to Ukraine in refrigerated rail cars and trucks, the piles of white plastic sacks a grim reminder of the cost of the worst conflict in Europe since World War II.

Grisly work of identifying bodies

Reuters spoke to eight experts, including police investigators, the Interior Minister, as well as Ukrainian and international forensic scientists and volunteers, and visited a forensic DNA laboratory in Kyiv.

Many of the bodies are decaying or in fragments, so such labs are key to identifying them. But the process of establishing and matching each DNA profile can take many months.

Since 2022, the Interior Ministry has expanded its DNA laboratories to 20 from nine, and more than doubled the number of forensic genetics scientists to 450, according to a deputy director of the ministry’s forensic research centre, Mr Ruslan Abbasov. But the start of large-scale swops was a shock.

“We were used to one, two, three, 10 (bodies), and they would come in slowly,” he said at a laboratory on the outskirts of Kyiv.

“Then it was 100, then it was 500. We thought 500 was a lot. Then there were 900, there were 909 and so on.”

Experts in protective gear and disposable overalls run DNA tests and match profiles to missing people. But some cases are so complicated that it can take up to 30 attempts to find a DNA match.

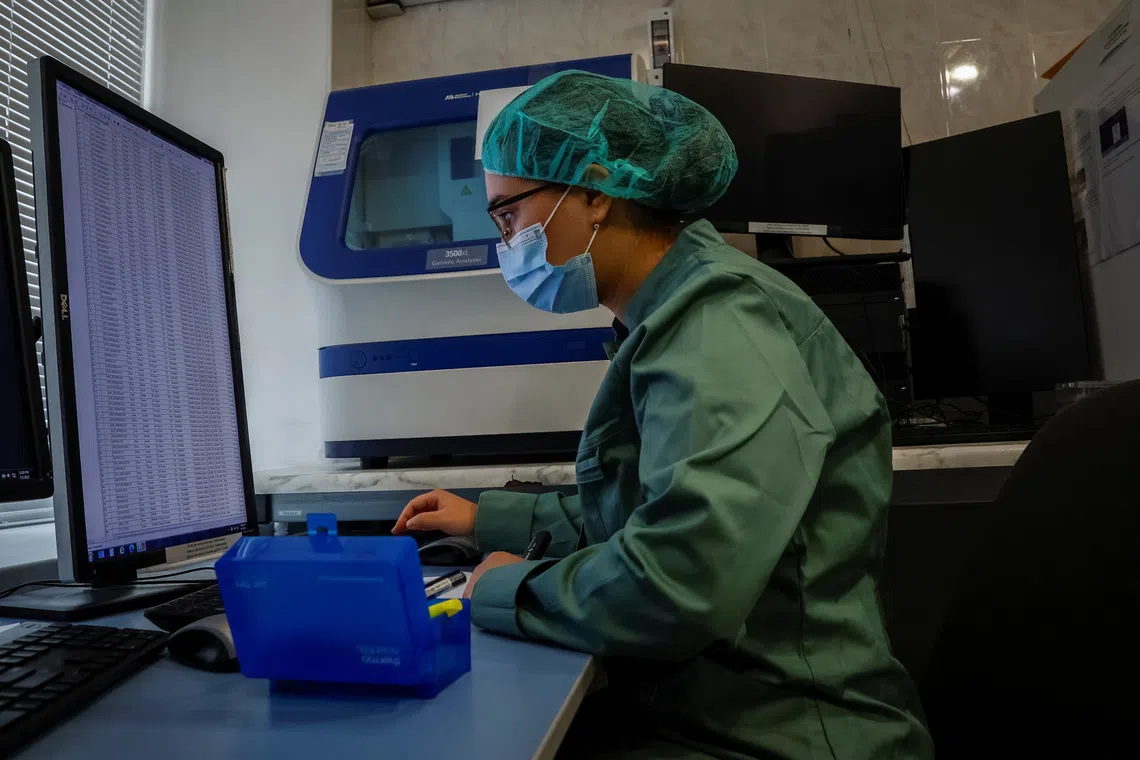

An employee of Ukraine’s state forensic centre working with results of DNA-testing materials to identify remains of bodies presumed to be Ukrainian service members.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Ukraine has only recently begun routinely collecting DNA samples from serving soldiers in case of disappearance or death, so investigators often face the much trickier task of using relatives’ DNA to find a match.

Soldiers’ bodies a reminder of Ukraine’s losses

As well as being a logistical challenge, the sudden influx of remains has served as a reminder of Ukraine’s losses.

The authorities in Kyiv and Moscow have been generally tight-lipped about the overall numbers of soldiers killed and wounded.

In June, the US-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies estimated that more than 950,000 Russians had been killed or wounded in the war so far, against 400,000 Ukrainians.

According to official figures, as at August, Ukraine had received 11,744 bodies. But 6,060 of these came in June alone, and another 1,000 in August.

The Ukrainian authorities declined to provide a figure for how many bodies Ukraine had sent back to Russia; it is a figure that could hint at how much territory Kyiv’s forces are losing, where they are unable to recover their dead.

Russian officials said they had received just 78 in June. Moscow’s Ukraine negotiator, Mr Vladimir Medinsky, suggested Ukraine was dragging its feet – something Kyiv denies.

Interior Minister Ihor Klymenko accused Russia of complicating the identification process by handing over some of the bodies in a disorderly way.

“We have many cases, probably hundreds, when we have remains of one person in one bag, then in a second and in a third,” he said at his ministry.

Mr Klymenko also said Ukraine had so far identified at least 20 bodies belonging to Russian servicemen – something for which Mr Medinsky said there was no evidence.

Russia’s Defence Ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

DNA samples key to identification

Since June 2022, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has participated in more than 50 repatriation operations and helped Ukraine with refrigerated trucks, body sacks and protective gear, said ICRC forensics coordinator Andres Rodriguez Zorro.

Once the bodies are in Ukraine, refrigerated trucks deliver them to morgues in different cities and towns.

In one of Kyiv’s morgues at the end of June, around a dozen men in white protective suits opened a refrigerated truck carrying about 50 bodies and carefully unloaded white body bags.

Staff members carrying a body, repatriated in a swop agreed between Russia and Ukraine earlier in June 2025, to a morgue.

PHOTO: REUTERS

As each was opened for checks, a sharp, sickly sweet smell filled the air. Investigators then took out smaller, black bags containing a body or body parts.

Police investigator Olha Sydorenko explained that initial checks were for unexploded ammunition, and also uniforms, documents, tags and other personal belongings. “We assign each body a unique identification number that accompanies them until the remains find their home,” she said outside the morgue, adding that she had become used to the smell.

She and her colleagues are the first point of contact for families of missing soldiers.

After learning from the military authorities that her husband was missing in action, Ms Tsvietkova opened a criminal case with the National Police, as prescribed, and submitted a description.

This included “everything that could help identify him. That is... his tattoos, his appearance, scars and moles”, she said.

She had one advantage – a sample of his DNA. “I brought his comb.”

Labs work in shifts, defying power cuts

But with so many bodies in the morgues, Mr Klymenko said it could take 14 months to identify them all. His teams work most hours of the day. The pristine lab in Kyiv is equipped with generators and batteries for potential power outages, which have become common as Russia bombs Ukraine’s electricity grid.

Teams work in shifts to maximise the use of space and equipment. The labs take samples from bodies and from relatives of the missing, usually when none of the missing soldier’s DNA is available.

“Sometimes you need to collect not only one sample from a relative, sometimes you need to collect two, three or four samples,” said ICRC’s Mr Zorro. “We are talking about hundreds of thousands of samples to be compared.”

Mr Abbasov said the most difficult cases were when bodies had been burned and their DNA degraded.

But Ms Tsvietkova does not want her husband identified by his DNA.

“... I’m waiting for Yaroslav to come back alive,” she said.

“I top up his (mobile phone) account every month so that he gets to keep his phone number. I write to him every day, telling him how my day went because when he returns, there will be a whole chronology of events that I lived through all this time, without him.” REUTERS