Thousands of prisoners in UK to be freed early to ease overcrowding

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

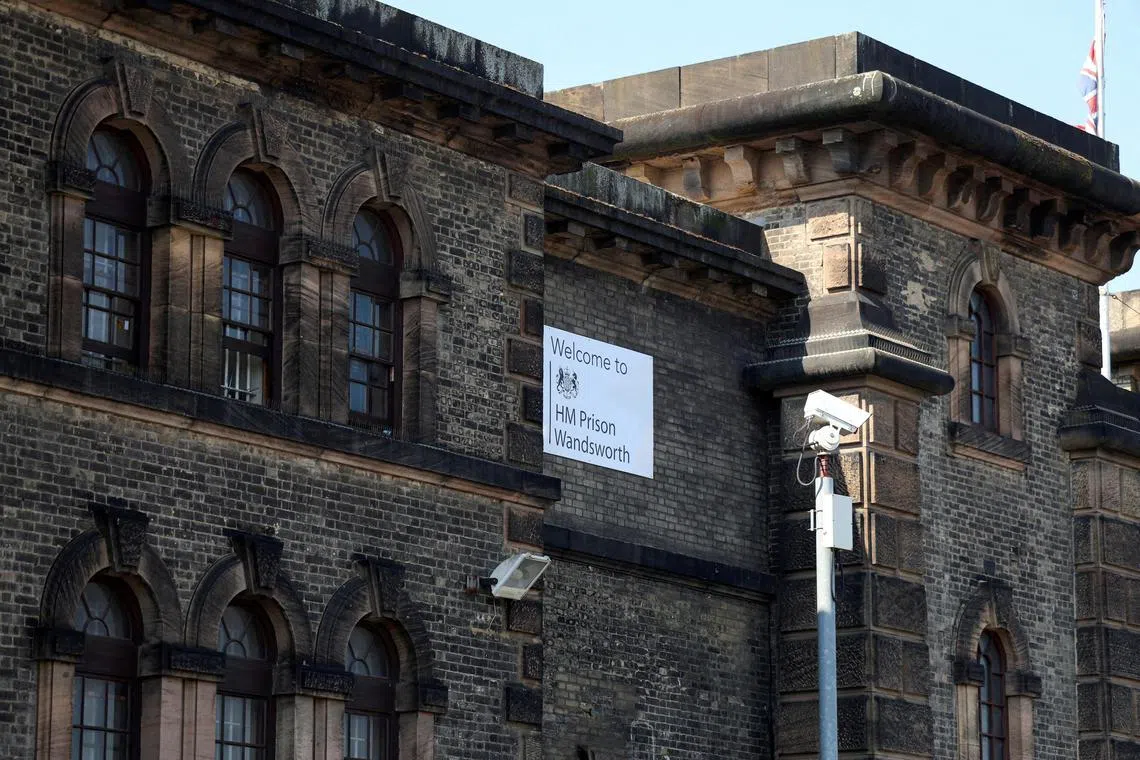

The Wandsworth prison in London in September 2023. In England and Wales, the prison population stands at 87,505 – very close to the maximum capacity of 88,956.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Follow topic:

LONDON – In one of its first big decisions, Britain’s new Labour government on July 12 announced the early release of thousands of prisoners, blaming the need to do so on a legacy of neglect and underinvestment under the Conservative Party, which lost last week’s general election

With the system nearly at capacity and some of the country’s aged prison buildings crumbling, the plan is aimed at avoiding an overcrowding crisis that some had feared might soon explode.

But with crime a significant political issue, the decision is a sensitive one and Prime Minister Keir Starmer, a former chief prosecutor, lost no time in pointing to his predecessors to explain the need for early releases.

“We knew it was going to be a problem, but the scale of the problem was worse than we thought, and the nature of the problem is pretty unforgivable in my book,” Mr Starmer said, speaking ahead of the decision while attending a Nato summit in Washington.

There were, he told reporters, “far too many prisoners for the prison places that we’ve got”.

“I can’t build a prison in the first seven days of a Labour government – we will have to have a long-term answer to this,” he added.

Under the new government’s plan, those serving some sentences in England and Wales will be released after serving 40 per cent of their sentence, rather than at the midway point at which many are freed “on licence”, a kind of parole.

The even earlier releases will not apply to those convicted of more serious crimes, including sexual offences, serious violence and terrorism.

But Mr Mark Icke, vice-president of the Prison Governors’ Association, told the BBC that the plan could remove from the system “between 8,000 and 10,000 people”, providing “some breathing space”.

Despite some early releases under the previous government, the strain on the prison system has been relentless.

In England and Wales, the prison population stands at 87,505 – very close to the maximum capacity of 88,956 – according to the latest official data.

The announcement on July 12 was made by new Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood, who visited two prisons in central England: Bedford, a facility built in the 19th century, and a newer one, Five Wells, in Wellingborough.

“Prisons are on the point of collapse,” Ms Mahmood said, adding that if space were to run out, the country would face the possibility of an overloaded justice system, with “looters running amok, smashing in windows, robbing shops and setting neighbourhoods alight”.

In a speech at Five Wells prison, Ms Mahmood also announced that 1,000 trainee probation officers would be recruited by March.

“If we fail to act now, we face the collapse of the criminal justice system. And a total breakdown of law and order,” she said.

In its first week in power, Labour has said that it is grappling with a difficult inheritance after years of restraint in spending on public services under the Conservatives.

In one of her first acts in government, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Ms Rachel Reeves, has ordered a review of Britain’s public finances.

Before Labour won the election, it had identified the strain on Britain’s prisons as a potentially major problem.

The issue was cited on an internal list of key concerns; others included the strain on the overburdened healthcare system and financial pressure on municipalities and universities.

The prison population of England and Wales has doubled over the last 30 years, despite a decline in crime rates, and it has increased by 13 per cent in the past three years.

Existing plans for building prisons also appear insufficient, with around 4,400 new spaces planned while the inmate population is projected to expand by an estimated 12,000.

More broadly, Britain’s entire criminal justice system is creaking, with a long backlog of cases waiting to be heard in courts, leaving a significant number of people in jail while awaiting trial for serious crimes.

Mr Rory Stewart, a former Conservative prisons minister, said Britain had incarcerated too many people, including for minor crimes such as repeated failure to pay council tax, which is levied by the local authorities for municipal services.

According to Mr Stewart in remarks to the BBC, imprisoning people for minor crimes “doesn’t protect the public”.

“It doesn’t help these people get away from offending. And it creates these violent, filthy, shameful places which our prisons have become today,” he said.

The Conservative and Labour parties, he added, had “competed with each other on being more and more ferocious in demanding longer and longer sentences”.

Mr Starmer has raised hopes among those who want to change that policy by appointing a prominent advocate of overhauling the prison system, Mr James Timpson, as prisons minister.

Mr Timpson, a businessman, has a record of employing former prisoners in an effort to give them a second chance.

The Prison Governors’ Association has welcomed the plan to allow earlier releases, saying in a statement that it was pleased at “the speed with which this new administration is moving to deal with the prison capacity crisis”.

“Time will be needed to take full advantage of the opportunities this relief will provide; prisons will not change overnight,” the statement added.

“The public must never be placed in this position again.” NYTIMES