Seniors in Germany head back to work, as ageing nation battles pensions burden

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

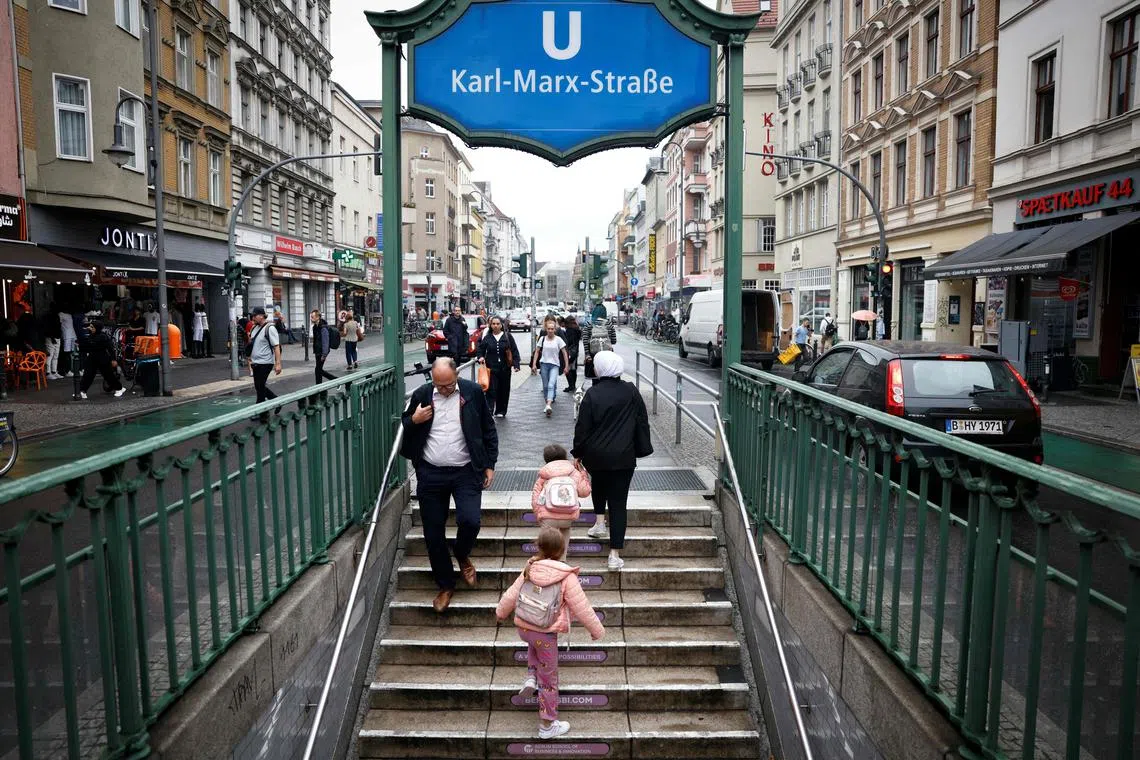

Retirees represent a quarter of Germany's population of 83 million, and workforce contributions are no longer enough to cover the cost of paying their retirement benefits.

PHOTO: EPA

- Germany faces a growing pension burden of €408 billion and a skilled labour shortage, prompting reforms to encourage seniors to work longer.

- Chancellor Merz proposes tax-free earnings of up to €2,000 a month for working seniors, but critics like Ms Schueler question its effectiveness and cost.

- Raising the retirement age to 70 is debated, with concerns about its impact on workers in physically demanding jobs despite potential budget benefits.

AI generated

COLOGNE, Germany - At age 70, Mr Pete Maie appears nervous at the start of a job interview to work as a part-time parcel delivery driver for a German logistics company.

“It’s a little stressful but I’m happy to be here,” said the former soldier and retired logistics manager, a blue shirt tucked neatly into his trousers.

Five years after he formally retired, Mr Maie is re-entering the labour market with the help of specialised recruitment agency Unique Seniors.

“I’m available immediately and ready to work as long as my body allows,” he said.

If it were up to Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s government, many elderly people would follow Mr Maie’s lead to help fast-ageing Germany grapple with the twin challenges of a high pension burden and a shortage of skilled labour.

By 2024, the cost of the pension system had ballooned to €408 billion (S$615 billion) according to the Labour Ministry – a 60 per cent rise from 2010.

Retirees now represent a quarter of the national population of 83 million, and workforce contributions are no longer enough to cover the cost of paying their retirement benefits.

Meanwhile, the skilled labour shortage has seen employers as diverse as retail chains, banks and the armed forces compete frantically to attract young workers and trainees.

‘Autumn of reforms’

For many years, the healthy growth rates of Europe’s biggest, export-led economy ensured sufficient tax revenues to finance a generous welfare state.

The model is now showing strains as Germany has been mired in recession for two years, struggles with structural problems and faces tough competition from Asia, high energy costs and new trade barriers with the US.

Mr Merz has argued that the welfare state in its current form has become “unaffordable” – comments that rattled his junior coalition partners the Social Democrats (SPD), the country’s traditional workers’ party.

The SPD’s Labour and Social Affairs Minister, Ms Baerbel Bas, retorted with unusual bluntness, labelling such rhetoric “bulls**t”.

The conservative and business-friendly Mr Merz, undeterred, promised an “autumn of reforms”, vowing tough steps to rein in outlays from pensions to unemployment benefits.

Another goal of the conservatives is to have more people work longer. The legal retirement age, now 66, is already being raised and set to reach 67 by 2031.

Germany’s legal retirement age is set to reach 67 by 2031.

PHOTO: AFP

In 2024, more than 1.1 million seniors were already working beyond 67 out of a labour force of 46 million.

To put more seniors to work, Mr Merz would like to allow “those who are able to and who want it” to earn up to €2,000 tax-free a month.

‘Feeling useful’

Mr Maie said he is among those keen to keep working – and not just to supplement his monthly pension of €1,600.

“Today, I lack a mission, the feeling of being useful,” he confided.

Ms Ruth Maria Schueler, a specialist in senior employment at the IW Institute, said “most people who return to work after retirement don’t do so primarily for financial reasons”.

She said she was therefore sceptical about the reform, which she describes as a “tax giveaway” to wealthy seniors that would cost the state €2.8 billion a year.

By 2027, an independent commission must propose structural reforms to ensure the long-term future of the pension system.

Conservative Economy Minister Katherina Reiche recently reignited the debate by suggesting a legal retirement age of 70, sparking the ire of unions and the SPD.

Ms Bas charged that this would be “a pure and simple reduction in pensions for people who cannot reach that age”.

Economist Johannes Geyer of the Berlin-based DIW institute said that retirement at 70 would help the budget but could harm workers, especially those in physically demanding jobs.

Those in their 60s who are harder to retrain would more likely end up unemployed, said Dr Geyer.

Unique Seniors chief Tobias Bell said his agency’s model has a lot of promise despite some negative perceptions.

“Most of our client companies continue to discriminate against older workers,” he said, even as experience showed that this age group is “more productive and less absent” on average.

A case in point is another elderly worker who found a new position through Unique Seniors.

At 65, Mr Rainer Guntermann, officially retired for two years, now assembles semiconductors full-time near Cologne.

He proudly asserts he can more than hold his own among a team with many younger colleagues, given that he is “punctual, diligent and never sick”. AFP