CERNAVODA, ROMANIA (NYTIMES) - A row of hulking concrete domes loom along the Danube-Black Sea Canal in Cernavoda, about two hours east of Bucharest. Two of the structures house nuclear reactors feeding Romania's electrical grid. Two others were begun decades ago and are still waiting for completion - though, perhaps, not for long.

"We have major plans," said Mr Valentin Nae, the site director.

The nuclear complex was conceived during the regime of Nicolae Ceausescu, the communist dictator who ran Romania for a quarter of a century before he was overthrown and executed in 1989.

Ceausescu's strategy was to insulate Romania from the influence of the Soviet Union by having it generate its own electricity.

More than 30 years on, as much of Europe looks to cut ties to Russia's energy, the two reactors very cheaply supply about 20 per cent of Romania's electricity.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which shares a nearly 400-mile (644km) border with Romania, has strengthened Romania's push for energy independence.

Its ambitious energy plans include completing two of the Cernavoda plants and leading the way into a new type of nuclear technology called small modular reactors. It also wants to take full advantage of substantial offshore gas fields in the deep waters of the Black Sea.

Some see Romania, a nation of 21 million roughly the size of Oregon, as having the potential to become a regional energy powerhouse that could help wean neighbours in eastern and southern Europe from dependence on Moscow.

It is a goal shared in Washington and among some investors, who see business and strategic opportunities in a corner of the world that has flared hot in recent months.

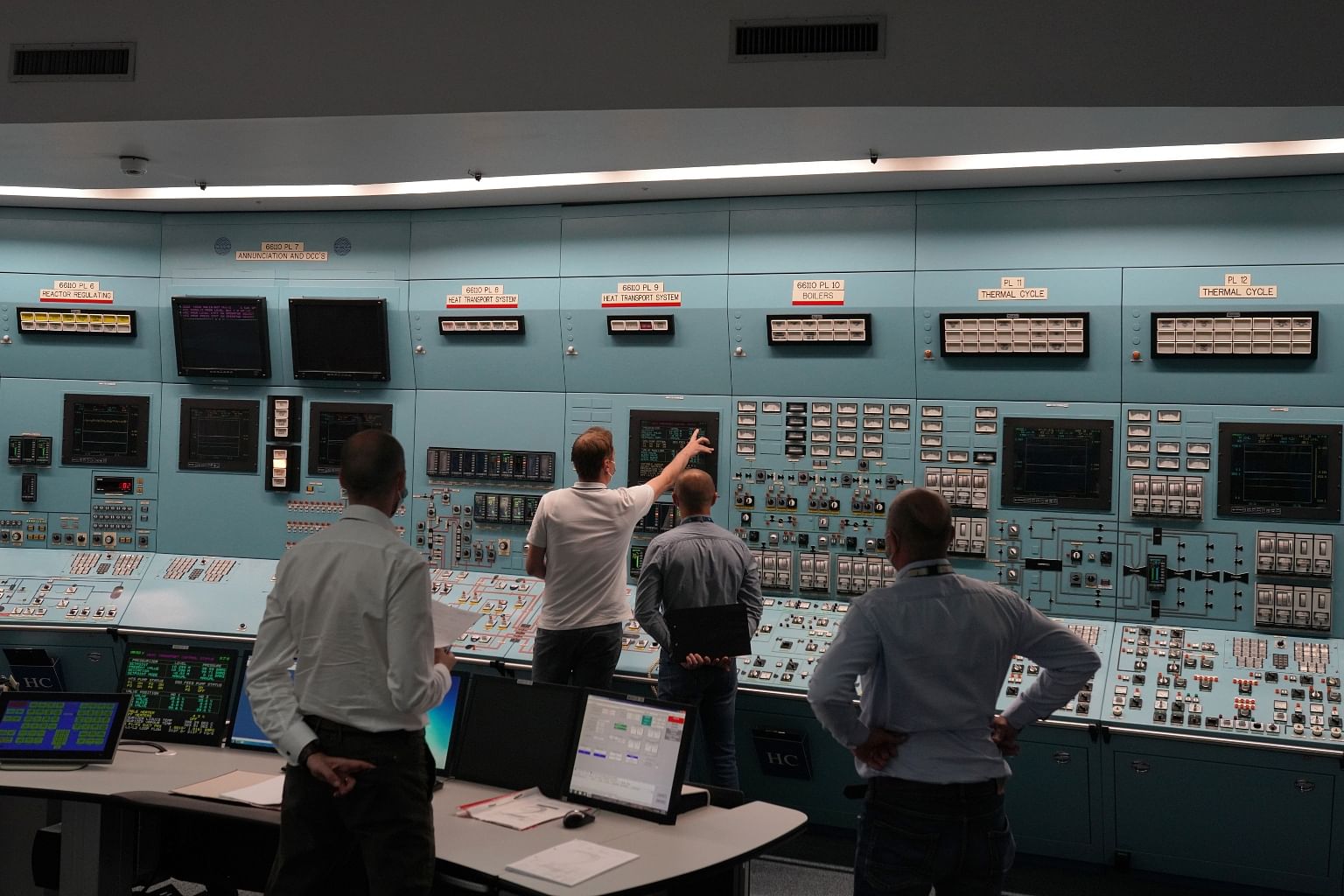

The owner of the Cernavoda nuclear complex, a state-controlled company called Nuclearelectrica, plans to spend up to 9 billion euros (S$13.04 billion) on nuclear initiatives this decade.

"We will supply energy security for the neighbourhood," Mr Virgil-Daniel Popescu, Romania's energy minister, said in an interview after lawmakers passed legislation designed to encourage investment in gas production.

Yet working in Romania will probably prove to be a challenge for companies from the United States and other Western countries.

The government has a reputation for greeting outside investors with cumbersome taxes and heavy-handed regulations. These policies, perhaps a result of fears that Romanian consumers would end up paying too much as energy giants took home hefty profits, have probably driven outside companies away.

Last month, for example, Exxon Mobil sold its 50 per cent stake in Neptun Deep, a Black Sea project that had been heralded as potentially the largest new natural gas production field in the European Union.

Exxon's brief announcement said the company wanted to focus on projects with "a low cost of supply." Romania's tax regime is considered Europe's toughest.

Romania's petroleum industry is one of the world's oldest, dating to the drilling of wells as far as back the 1860s and centred on the vibrant hub of Ploiesti, about 35 miles north of Bucharest.

While the venerable oil fields are on the wane, industry executives say drilling in the Black Sea could produce enough natural gas to turn Romania, now a modest importer, into the largest producer in the European Union.

"The opportunity resides in the offshore," said Ms Christina Verchere, chief executive of OMV Petrom, Romania's largest oil and gas company.

While plans for Cernavoda are grinding forward, the Romanian government and the Biden administration announced in May a preliminary agreement to build a so-called small modular reactor at the site of a shuttered coal-fired power plant.

The provider would be an Oregon company, NuScale Power, which has received more than US$450 million (S$624.45 million) in support from Washington to develop what the nuclear industry hopes will be a new technology to revive reactor building.

The idea is to build components for the plants in factories and then assemble them at the site with the hope of cutting the enormous costs and long construction times that have hampered the nuclear industry.

Over time, these reactors could provide European countries with an alternative to polluting coal and imported gas from Russia.

"Europe must find trusted sources of clean and reliable energy, sources free of coercion and malign political influence," said Mr David Muniz, the charge d'affaires at the US Embassy in Bucharest, at a news conference announcing the NuScale deal.

For a country like Romania with a well-trained, low-cost workforce, experts say, making equipment for this new type of reactor could turn into an export industry, not to mention the chance to export surplus electricity.

"I believe it is an immense opportunity," said Mr Ted Jones, senior director for strategic and international programs at the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry group in Washington.

Yet the Romanian government is likely to keep close watch on investors and try to insulate Romanians from global economic forces. Outside of the faded elegance of some districts of Bucharest, Romania is a relatively poor country, its median income ranking near the bottom in the European Union.

"There is an ingrained mistrust in the private market," said Mr Radu Dudau, director of the Energy Policy Group, a non-profit in Bucharest. "There is an underlying understanding and expectation that the people and the nation will be safer if the state controls it."

A small gas field in the Black Sea began operating Wednesday (June 15). Owned by a group including a unit of Carlyle, the US investment management firm, the project will pipe fuel ashore near Constanta, Romania's major port and offshore drilling center. Eventually, it will produce about 10 per cent of Romania's gas needs.

Developing Neptun, estimated at US$4 billion, is likely to be more difficult and expensive than if the work had begun a few years ago.

With high oil and gas prices, costs of drilling and steel and other inputs have soared. The Black Sea is a risky area now with mines floating around and the perils from Russian military activity adding to insurance rates.

Exxon also has far greater expertise in operating in deep water than Romgaz or OMV Petrom, which has taken over from Exxon as operator of the project.

Despite those issues, concerns over energy security are so strong that the project seems likely to go ahead, even with Exxon gone, analysts say. It may even help that two Romanian companies are in charge.

"I think it definitely has the right context now," Mr Verchere, the OMV Petrom chief executive, said.