Nobel Prize-winning scientists built on each other's work to develop lithium-ion batteries

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

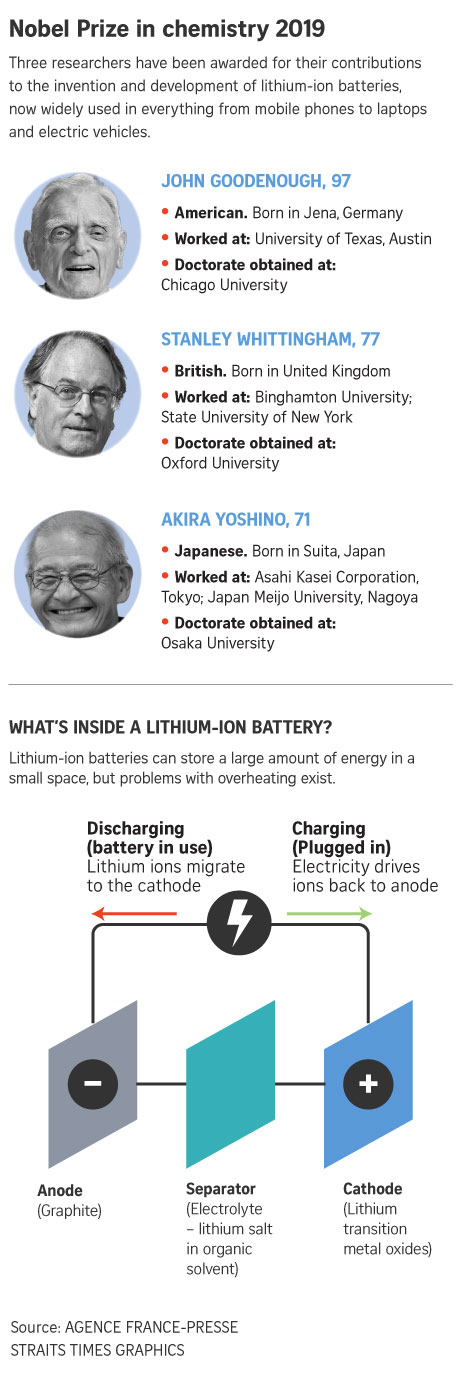

Today, rechargeable lithium-ion batteries provide energy to mobile phones, pacemakers and electric cars, thanks to the work of scientists (from left) John Goodenough, M. Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino.

PHOTO: AFP

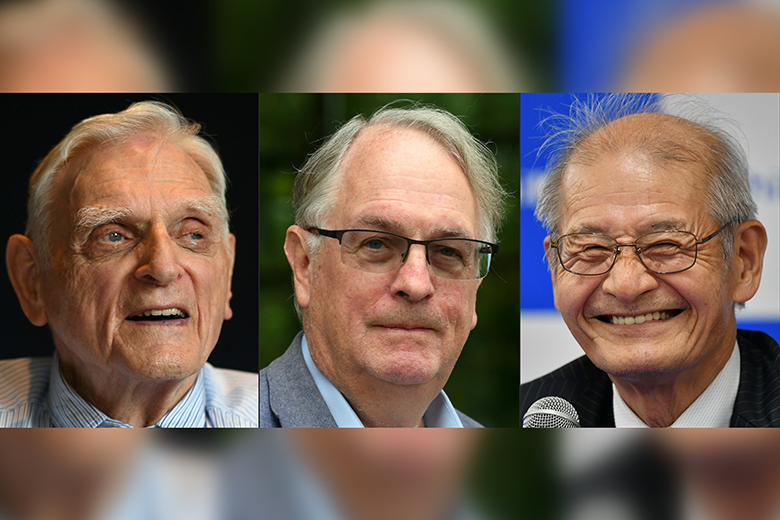

WASHINGTON (WASHINGTON POST) - The three scientists awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing rechargeable lithium-ion batteries had researched the reactive element and built on each other's work over decades.

Lithium is a soft, silver-white metal that first formed minutes after the Big Bang, and is also created when cosmic rays strike interstellar gas. Pure lithium is so reactive that it must be kept in oil. The element fizzes and belches gas when it touches water.

Today, rechargeable lithium-ion batteries provide energy to mobile phones, pacemakers and electric cars, thanks to the work of John Goodenough, M. Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino.

Professor Whittingham, born in the United Kingdom and a professor at Binghamton University in New York, was recruited to work at Exxon in the 1970s. While investigating materials able to hold particles in atom-size gaps, he discovered that titanium disulfide houses lithium ions. This energy-rich material excited Exxon management - until the first lithium batteries began to short-circuit and catch fire.

"They had a few explosions, and decided to get out of the alternative-energy business," Professor Goodenough told the New Yorker in 2010.

German-born Prof Goodenough, a 97-year-old engineering professor at the University of Texas in Austin, is the oldest person to receive a Nobel Prize. He improved the batteries in 1980 by swapping out the titanium disulfide, in the cathode end of the batteries, for cobalt oxide.

Batteries doubled their energy potential because of the cobalt oxide - an insight "that was really outside the box at the time", said Ms Bonnie Charpentier, president of the American Chemical Society.

Mr Yoshino, of Japan, developed the first commercial lithium-ion battery five years later when he made another swap: This time, exchanging reactive lithium in the anode for a carbon-based material, petroleum coke. Mr Yoshino's removal of pure lithium reduced the risk of explosions. He suffused that coke with electrons, whose negative charges lured the positive lithium ions out of the cobalt cathode. When the battery was turned on, the ions and electrons flowed back to the cathode.

As these particles shuttled from end to end, unlike in traditional batteries, they did not chemically react. Together, these discoveries produced a lightweight battery that can recharge hundreds of times without faltering, the Nobel committee said.

"The beauty of it is they built on each other's work to solve problems that really needed solving," Ms Charpentier said.

In corners of the world that lack electrical infrastructure, she said, people can now access the Internet through mobile phones charged by small solar panels - technologies with lithium batteries at their hearts. "It truly is a life-changing invention for many people," Ms Charpentier said.

Researchers are working to refine rechargeable batteries, using new materials to improve their capacity and efficiency.

"Climate change is a very, very serious issue for humankind," said Mr Yoshino, who phoned in to the conference in Sweden. Batteries able to store power from renewable sources lessen dependence on fossil fuels.

"We're all very happy" the Nobel committee recognised a practical technology, Prof Whittingham said from Ulm, Germany, where he was at a conference to discuss automotive battery development. "It's a very good trio," he said. "We complemented each other very well."

"Live to 97 (years old) and you can do anything," Prof Goodenough said in a statement. "I'm honoured and humbled to win the Nobel Prize. I thank all my friends for the support and assistance throughout my life."