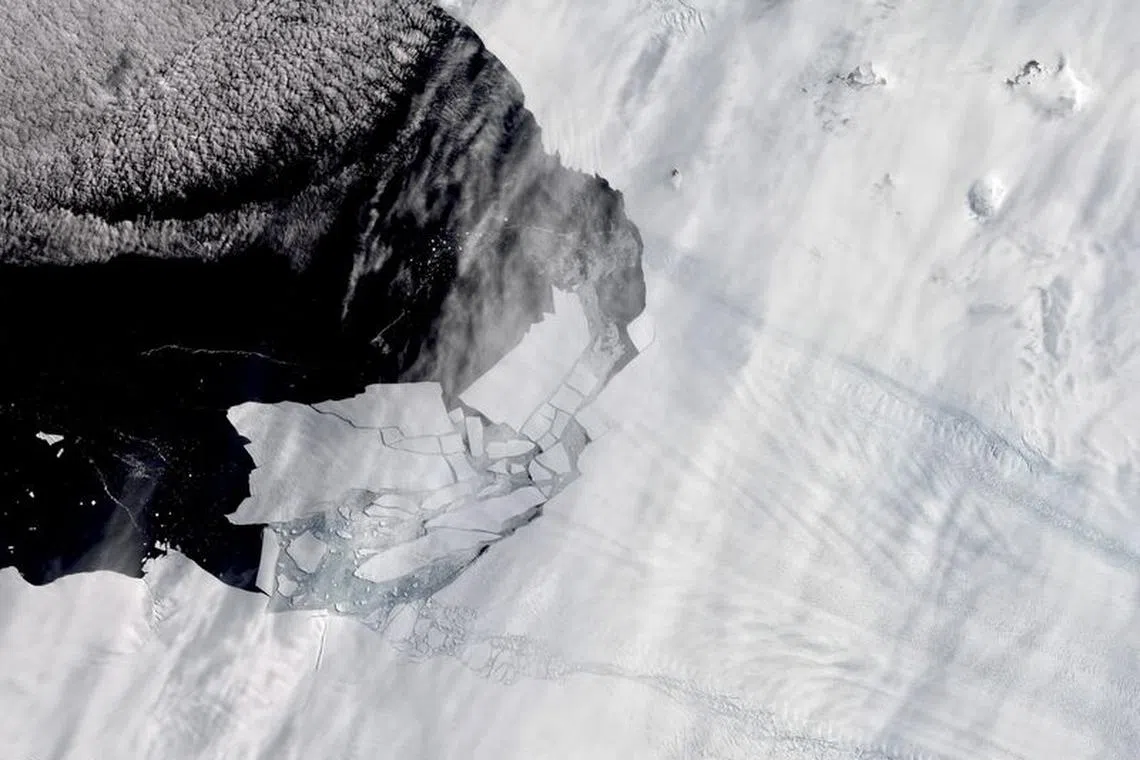

Meltdown of West Antarctic Ice Sheet unavoidable, study says

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Sea levels will rise over the coming decades regardless of how much the world slashes planet-warming emissions.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Follow topic:

LONDON - At the bottom of the world, the floating edges of one of the enormous ice sheets covering Antarctica are facing an invisible threat, one that could add to rising sea levels around the globe: They are melting from below.

As the planet warms,

Now, researchers in Britain have run the numbers and come to a sobering conclusion: A certain amount of accelerated melting is essentially locked in. Even if nations limited global warming to 1.5 deg C,

“It appears that we may have lost control of the West Antarctic ice shelf melting over the 21st century,” one of the researchers, Dr Kaitlin Naughten, an ocean scientist with the British Antarctic Survey, said at a news briefing. “That very likely means some amount of sea level rise that we cannot avoid.”

The findings by Dr Naughten and her colleagues, which were published on Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, add to a litany of gloomy predictions for the ice on the western side of the frozen continent.

Two of the region’s fastest-moving glaciers, Thwaites and Pine Island, have been losing vast amounts of ice to the ocean for decades. Scientists are trying to determine when greenhouse gas emissions might push the West Antarctic ice sheet past a “tipping point”, beyond which its collapse becomes rapid and hard to reverse, imperilling coastlines worldwide in the coming centuries.

Even so, cutting emissions of heat-trapping gases could still stop even greater amounts of Antarctic ice from being shed into the seas. The East Antarctic ice sheet contains about 10 times as much ice as the West Antarctic one, and past studies suggest that it is less vulnerable to global warming, even if some recent research has challenged that view.

“We can still save the rest of the Antarctic ice sheet,” said Professor Alberto Naveira Garabato, an oceanographer at the University of Southampton who was not involved in the new research, “if we learn from our past inaction and start reducing greenhouse gas emissions now.”

Dr Naughten and her colleagues focused on the interplay between the ice shelves and the water in the Amundsen Sea, which is the part of the Southern Ocean that washes up against the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers.

The researchers first used computer simulations to estimate changes in ocean temperature and the resulting ice-shelf melting that took place there in the 20th century. They then compared this with potential changes under several pathways for global warming in the 21st century, from highly optimistic to unrealistically pessimistic.

They found that the water at 200m to 700m beneath the surface of the Amundsen Sea could warm at more than three times the rate in the coming decades compared with the last century, regardless of what happens with emissions.

If global warming were limited to 1.5 deg C compared with pre-industrial conditions, temperatures in the Amundsen would flatten out somewhat after about 2060. In the most calamitous emissions trajectory, by contrast, ocean warming would accelerate even more after 2045.

The reason the differences are not bigger is that water temperatures in this part of the Southern Ocean are influenced not just by human-driven warming of the atmosphere, but also by natural climate cycles such as El Nino, Dr Naughten said. The differences under the various emissions trajectories, she said, are small by comparison.

The study is unlikely to be the last word on the future of the West Antarctic ice shelves. Scientists began collecting data on melting there only in 1994 and, because of the difficulty of taking measurements in such extreme conditions, the data is still sparse.

“We are relying almost entirely on models here,” Dr Naughten said.

When mathematical representations of reality are the best option available, scientists prefer to test their hypotheses using multiple ones to make sure their findings are not the product of a given model’s quirks. Dr Naughten and her colleagues used only a single model of the interactions between ice and ocean.

Still, their study’s methods are broadly in line with past findings, said Dr Tiago Segabinazzi Dotto, a scientist with the National Oceanography Centre in Britain who was not involved in the new research.

This gives coastal societies reason to take the study’s predictions seriously and to plan for even higher sea levels, he said. NYT