In Moscow, the war with Ukraine is background noise – but ever present

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

There is little anxiety among residents over the drone strikes that hit Moscow this summer.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Follow topic:

MOSCOW – Metro trains are running smoothly in Moscow, as usual, but getting around the city centre by car has become more complicated, and annoying, because anti-drone radar interferes with navigation apps.

There are well-off Muscovites ready to buy Western luxury cars, but there are not enough available. And while a local election for mayor took place as it normally would this month, many of the city’s residents decided not to vote, with the result seemingly predetermined (a landslide win by the incumbent).

Almost 19 months after Russia invaded Ukraine,

This month, Moscow is aflutter in red, white and blue flags for the celebration of the Russian capital’s 876th anniversary. Its leaders marked the occasion with a month-long exhibition that ended on Sept 10.

Featuring the country’s largest hologram, it showcased the city of 13 million people as a smoothly operating metropolis with a bright future. More than seven million people visited, according to the organisers.

There is little anxiety among residents over the drone strikes that hit Moscow this summer,

When flights are delayed because of drone threats in the area, the explanation is usually the same as the one plastered on signs at the shuttered luxury boutiques of Western designers: “Technical reasons”.

The city continues to grow. Cranes dot the skyline, and there are high-rise buildings going up all over town. New brands, some home-grown, have replaced foreign flagship stores, including Zara and H&M, which departed after the invasion began in February 2022.

“We continue to work, to live and to raise our children,” said Ms Anna, 41, as she walked by a pavement memorial marking the death of Wagner mercenary leader Yevgeny Prigozhin. She said she works in a government ministry, and like others interviewed, she did not give her last name because of a fear of retribution.

But for some, the effects of war are landing harder.

Ms Nina, 79, a pensioner who was shopping at an Auchan supermarket in north-western Moscow, said that she had stopped buying red meat entirely and that she could almost never afford to buy a whole fish.

“Just right now, in September, the prices rose tremendously,” she said.

Ms Nina said that sanctions and ubiquitous construction projects were some reasons for higher prices, but the main reason, she said, was “because a lot is spent on war”.

“Why did they start it at all?” she added. “Such a burden on the country, on people, on everything. And people are disappearing – especially men.”

Authorities have worked to limit public expressions of dissent and make things seem as normal as possible.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

When asked about the biggest problems facing Russia, more than half the respondents in a recent poll by the independent Levada Centre cited price increases.

The war in Ukraine, known in Russia as the “special military operation”, came in second with 29 per cent, tied with “corruption and bribery”.

“Everything is getting more expensive,” said Mr Aleksandr, 64, who said he works as an executive director in a company. His shopping habits at the grocery store have not changed, but he said he has not traded in his luxury Western-branded car for a newer model.

“First of all, there are no cars,” he said, noting that most Western dealerships have left Russia and that Chinese brands have been taking their places on the roads.

The war has made itself evident outside supermarkets and car dealerships. Moscow may be one of the few cities in Europe without sold-out showings of the movie Barbie.

Warner Bros, which produced the film, pulled out of Russia shortly after President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine, and bootleg copies of Barbie were shown only in a few underground screenings.

The election for mayor also underscored the sea change in Russian politics.

A decade ago, opposition politician Alexei Navalny stood as a candidate against Mr Sergey Sobyanin.

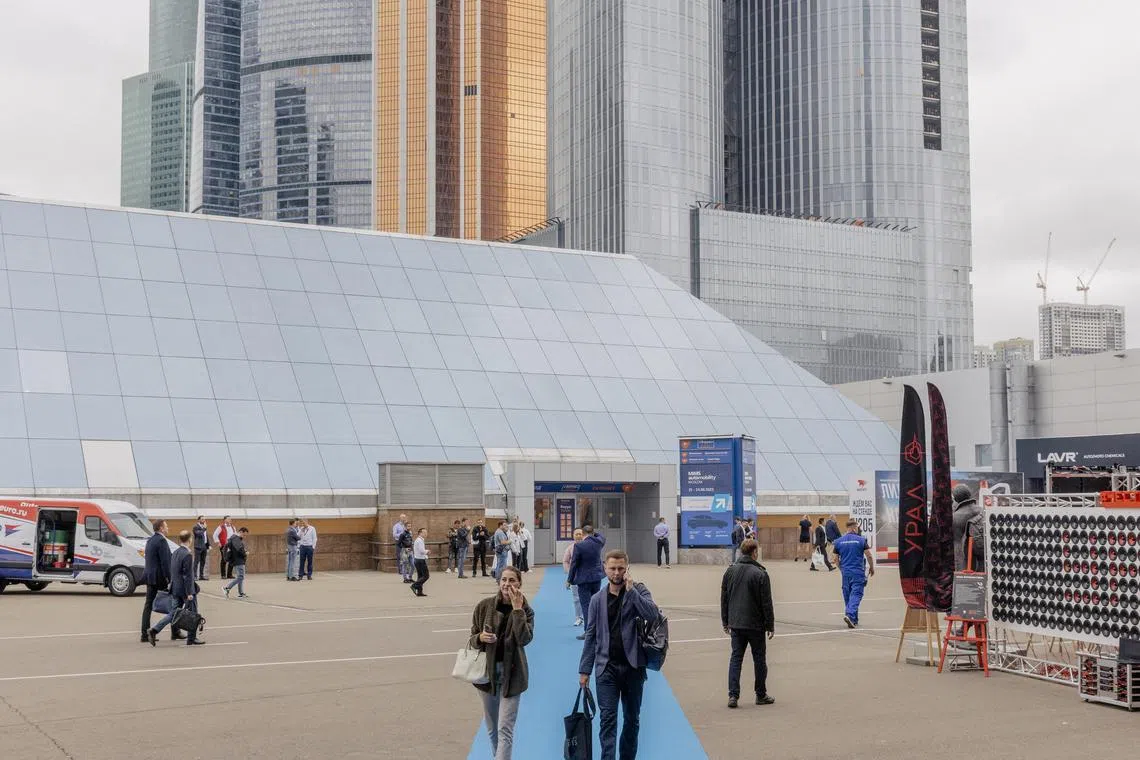

A public space in the Moscow City business district, where there were several drone attacks during this summer.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Now Navalny, 47, is in jail, and there was no real competition for Mr Sobyanin, 65, who won a third term with an unprecedented 76 per cent of the vote.

Other parties, including the Communist Party, fielded a candidate against the incumbent, but they are all considered “systemic opposition” parties, or groups in Parliament nominally in opposition but who align their policies with the Kremlin on most issues.

“Before the war, I still voted,” said Mr Vyacheslav Bakhmin, a chair of the Moscow Helsinki Group, the oldest human rights group in Russia. “I don’t want to vote now because, well, the result seems to be clear, right?”

As Mr Putin presides over a war with no end in sight, the authorities have worked to limit public expressions of dissent and make things seem as normal as possible.

Mr Alexei Venediktov, who headed the liberal Echo of Moscow radio station before the Kremlin shut it down in 2022, said that the government has engineered the war’s absence from political spaces.

Mr Aleksei Venediktov, who headed the Echo of Moscow, said the government had engineered the war’s absence from political spaces.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

“This war, it is mainly on TV or on Telegram channels, but it is not on the street. It is not even discussed in cafes and restaurants because it is dangerous, because the laws that have been adopted are repressive,” Mr Venediktov said.

He noted cases where people expressing anti-war views were denounced – or in some cases reported to the police – by those sitting next to them on the subway or in restaurants.

“People prefer to tell one another, ‘Let’s not talk about it here,’” Mr Venediktov said. “And that’s why you can’t see it in the mood.”

In Moscow City, an area of skyscrapers that is the Russian capital’s answer to New York’s Financial District, many people casually dismissed a series of drone strikes that damaged some of the buildings there but resulted in no casualties.

One woman, Ms Olga, who said she works nearby, just nodded as a colleague shrugged off the potential risk.

Muscovites go about their daily lives with little major disruption.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Later, Ms Olga sent a New York Times journalist a message on the Telegram messaging app: “I couldn’t say anything because at work they don’t talk about a position like mine,” she wrote. “I am against war and I hate our political system.”

When there is a drone strike inside Russia, “I always hope that maybe someone will think about what it means to live under shelling, and regret the loss of our normal life before the war”, she added.

She said that if the explosions do not cause casualties, then “I don’t regret damage to the buildings at all”.

Mr Venediktov said that even if changes on Moscow’s surface are hard to see and increasingly harder to discuss, people are truly transforming inside.

“People are starting to return to the Soviet practice, when public conversations can lead to trouble at work,” he said.

“It’s like toxic poisoning – a very slow process.”

NYTIMES