News analysis

Germany’s ban on chip factory sale shows hardening stance in Europe towards China

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The move indicates hardening attitudes throughout Europe about the purchase of technology companies by Chinese commercial entities..

PHOTO: EPA-EFE

LONDON – The German government has blocked the planned sale of a chip factory to a Chinese group

The move indicates hardening attitudes throughout Europe about the purchase of technology companies by Chinese commercial entities.

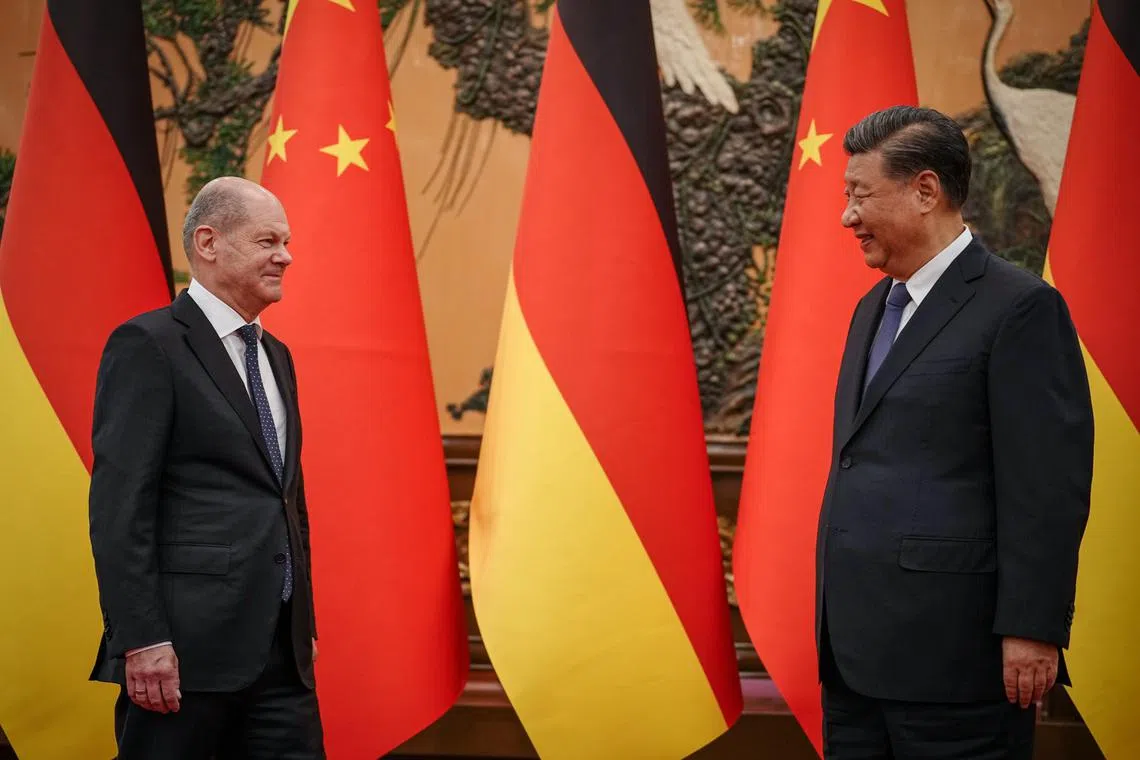

And, in a further twist that is likely to increase China’s displeasure, the cancellation of the chip factory purchase comes barely a week after German Chancellor Olaf Scholz became the first Western leader to travel to Beijing

German company Elmos Semiconductor employs 1,300 workers worldwide, of whom 225 are assigned to the production of chips at a facility in the industrial town of Dortmund. Its products are primarily intended for use in cars.

Last December, the company agreed to sell its Dortmund factory to Silex Microsystems, a company based in Sweden but wholly owned by Chinese group Sai MicroElectronics.

The deal was referred to the German government under regulations introduced over the past few years, allowing European Union member-states to scrutinise and disallow, if necessary, foreign acquisitions.

At first sight, the proposed acquisition raised few objections.

The Dortmund-based company is a minor player in the semiconductor business, significantly smaller than Germany’s Infineon, the world’s leading manufacturer of semiconductors for the automotive industry. Elmos also produces only 40 per cent of the chips, getting the rest from contract manufacturers or foundries, as they are known in the industry.

The technology involved in its chip production is not cutting-edge. And the value of the acquisition is a mere €85 million (S$120 million). So, the assumption was that the deal would be allowed to go through.

“I think this takeover of a German chip manufacturer by a Chinese company is justified because it is not a critical infrastructure,” said Dr Marcel Fratzscher, who runs the highly respected German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin.

But to almost everyone’s surprise, Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs announced that the sale was prohibited.

“Germany is and will remain an open investment location,” Economics Minister Robert Habeck said, “but we are not naive either… especially in the semiconductor sector, it is important to protect the technological and economic sovereignty of Germany and Europe.”

In a statement to the Shanghai Stock Exchange, where its shares dropped by 7 per cent on news of the German action, Sai MicroElectronics said it “deeply regrets the decision” but also claimed that it remained “optimistic” about its prospects in the auto chip industry.

According to German media reports, the decision to ban the sale was heavily influenced by objections voiced by the bosses of both the Federal Intelligence Service – Germany’s foreign spying agency – and the country’s internal security service, which operates under the name of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution.

Yet a far more plausible explanation is that the acquisition fell foul of political trends in Germany.

The opposition Christian Democrats used the proposed sale to criticise the government of Chancellor Scholz for its alleged weakness in facing security threats

“We are promoting semiconductor production in Germany with billions of euros to become more independent of China and the Taiwan conflict. And now we propose to sell our semiconductor production to China? You couldn’t make it up,” tweeted Mr Jens Spahn, the Christian Democrats’ deputy chair.

But of much greater significance is the position of the Greens, the second-largest partner in Chancellor Scholz’s coalition government.

The Greens – who have long adopted a highly critical stance on China – were irritated by Mr Scholz’s recent decision to overrule their opposition and authorise the sale of 25 per cent of the northern German port of Hamburg to China’s Cosco shipping giant.

The Greens also disagreed with the Chancellor’s latest trip to China, which was undertaken despite their objections.

The Ministry for Economic Affairs is in the hands of the Greens, so the urge to retaliate against the Chancellor’s stance probably played a significant role in the decision to scupper the semiconductor acquisition.

“We hope that Germany and other countries will provide a fair, open and non-discriminatory market environment for Chinese companies doing business there, and refrain from politicising normal economic and trade cooperation, still less using national security as a pretext to practise protectionism,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said in response to the German decision.

However, Beijing would be wrong to conclude that the latest ban is a one-off event connected entirely to Germany’s domestic politics.

The need to block Chinese acquisitions of cutting-edge technologies and diversify away from Chinese-controlled critical industrial sectors is accepted across the entire spectrum of Germany’s political elite.

There are currently 40 other cases of acquisition projects under consideration by the German government, with around half of these involving Chinese interests.

And, according to media sources inside Germany, the government has already banned another proposed Chinese acquisition, although officials have refused to provide any details.