LONDON - The routine never changes. In one single week in June, hundreds of thousands of students in high schools across France sit down for a series of examinations. The experience is a nerve-racking rite of passage which haunts every 18 year-old French teenager and their families. These are the Baccalaureate examinations which are an absolute necessity for getting on in life in France.

Throughout the world, the "Bac" - as it is invariably called in France - is synonymous with rigorous teaching and academic excellence. But, as the current French government now acknowledges, the Bac no longer meets these aspirations, so the authorities are proposing to overhaul the system.

Yet the reform has already generated a storm of protest. For any measure touching the Baccalaureate is seen as an assault upon a national institution which defines the essence of France.

The Baccalaureate was introduced by Emperor Napoleon in 1808 to ensure that all French schools uphold a uniform national education standard. It has inspired but is unconnected to the International Baccalaureate, which is currently offered by schools around the world, including by some in Singapore.

France's Baccalaureate is divided into three types - general, professional and technological - with the "general" type being further divided into "scientific", "socio-economic" and "literary" streams, each denoting different combinations of exam papers.

Each stream or combination is identified by an alphabet letter and, to confuse matters even further, the strands were overhauled in 1994 and given different letters, but older generations of parents and teachers still refer to the current strands by their old letter titles.

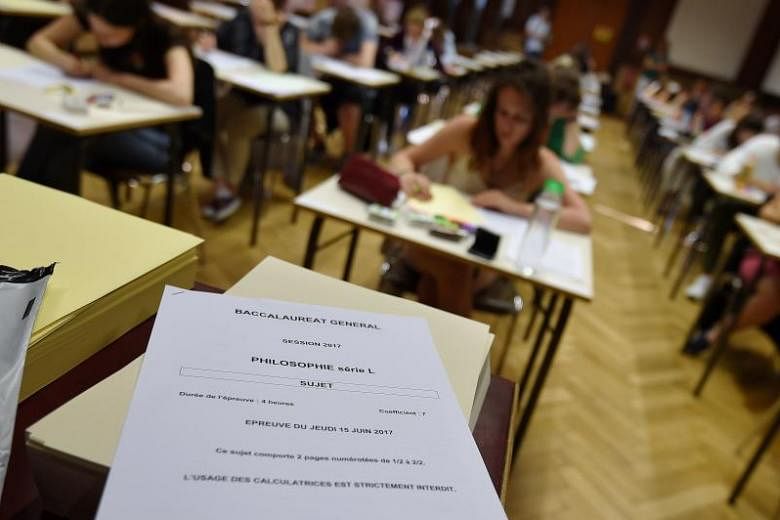

It may be incomprehensible to outsiders, but makes sense to the French, who know the routine. Throughout France and its territories as far as the Pacific, they all arrive in a hall, and take a number. With a dramatic flurry, the super-secret exam papers are unsealed, not by just any invigilator but only by a school principal. All exams are to be answered in a lengthy essay format, and each Bac candidate sits about 10 such papers in a week.

Those who get the yellow-coloured Baccalaureate diploma are guaranteed a university place at the state's expense; those who don't will struggle. A total of 718,000 French youngsters sat in last year's Baccalaureate, and their papers were marked by 170,000 examiners. It is an expensive operation, but one touted by generations of French politicians as necessary and fair.

No longer, however. As elsewhere in the industrialised world, parents complain that the Bac is too rigid, puts unnecessary strain on youngsters and forces them to specialise at a tender age.

Educators complain that the system is antiquated, provides students with few practical skills and suffers from "grade inflation"; the percentage of those passing with "honours" has doubled over the past decade.

And government officials fret that the Bac does not prepare students for university courses; currently at 1.6 million, student numbers in France are at their highest, but only 40 per cent graduate on time.

Mr Jean-Michel Blanquer, France's National Education Minister, has just unveiled proposals to overhaul the entire system.

Entitled "Bac 2021", Mr Blanquer's reform package is proposing to reduce the number of exams students have to take from the current 10 to an average of only four, as with the A levels in the British education system; some of the other topics taught will either be examined before the final school year, or be subjected to continuous assessment.

The centrepiece of the reforms is, however, the proposed introduction of an oral exam, in which students will be asked to present before a jury of three examiners over a period of half an hour a research project of their choosing.

The proposed test - promptly named by the French media as the "Grand Oral" - is intimidating, admits Mr Blanquer. But he says it is necessary to encourage youngsters' presentational skills and creativity.

The predictable howls of protest followed. "In oral tests, the form counts much more than the content", complains noted French sociologist Pierre Merle, who claims that the oral exam won't encourage creativity, but discriminate against students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Teachers' trade unions are also against the proposals; they will lead to "the fragmentation of evaluation methods", claims Frederique Rolet, who runs SNES, representing 62,000 high school teachers.

The French government vows to persevere. But it also knows that all previous governments in Paris over the past quarter of a century have tried to change the Baccalaureate, and all have been defeated by the combined forces of tradition and inertia.

For despite all its acknowledged faults, most French citizens retain a deep emotional attachment to their Bac.

"To suppress it would be like dismantling the Eiffel Tower", says Xavier Darcos, a former education minister.