Europe’s space telescope Euclid takes off to explore universe’s dark mysteries

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

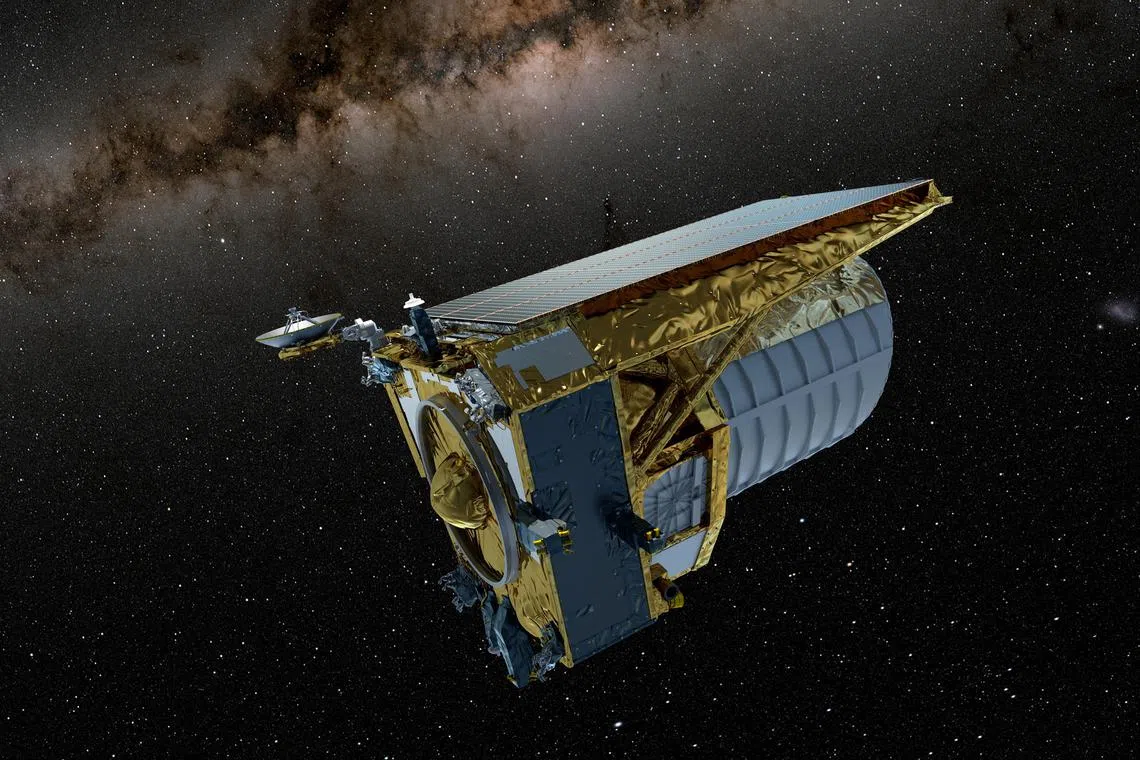

Euclid will chart the largest-ever map of the universe.

PHOTO: REUTERS

KENNEDY SPACE CENTRE – Europe’s Euclid space telescope was launched on Saturday on the first-ever mission aiming to shed light on two of the universe’s greatest mysteries: dark energy and dark matter.

The telescope was carried aloft in the cargo bay of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket that blasted off around 11.12am Eastern Daylight Time (11.12pm Singapore time) from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

A live streaming of the lift-off was shown on Nasa TV.

The European Space Agency was forced to turn to billionaire Elon Musk’s firm to launch the mission after Russia pulled its Soyuz rockets in response to sanctions over the war in Ukraine.

After a month-long journey through space, Euclid will join its fellow space telescope James Webb

From there, Euclid will chart the largest-ever map of the universe, encompassing up to two billion galaxies across more than a third of the sky.

By capturing light that has taken 10 billion years to reach Earth’s vicinity, the map will also offer a new view of the 13.8-billion-year-old universe’s history.

Scientists hope to use this information to address what the Euclid project manager Giuseppe Racca calls a “cosmic embarrassment”: that 95 per cent of the universe remains unknown to humanity.

Around 70 per cent is thought to be dark energy, the name given to the unknown force that is causing the universe to expand at an accelerated rate.

The other 25 per cent is dark matter, thought to bind the universe together and make up around 80 per cent of its mass.

“Ever since we could see stars we’ve wondered, is the universe infinite? What is it made out of? How does it work?” Nasa Euclid project scientist Michael Seiffert told AFP.

“It’s just absolutely amazing that we can take data and actually start to make even a little bit of progress on some of these questions.”

‘Dark detective’

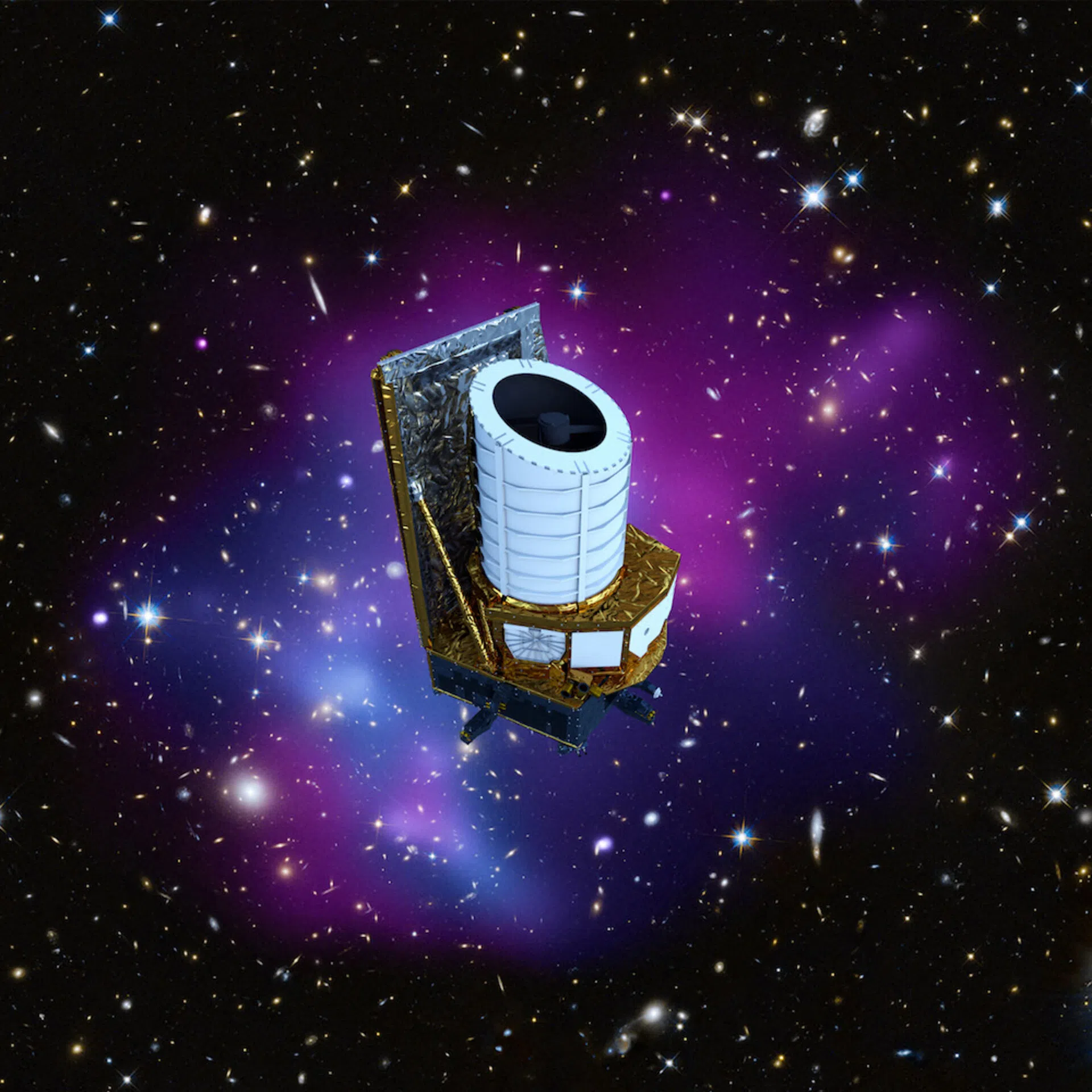

Euclid consortium member Guadalupe Canas told a press conference that the two-tonne space telescope was a “dark detective” which can reveal more about both elements.

Euclid, which is 4.7m tall and 3.5m wide, will use two scientific instruments to map the sky.

Its visible light camera will let it measure the shape of galaxies, while its near infrared spectrometer and photometer will allow it to measure how far away they are.

Euclid, which is 4.7m tall and 3.5m wide, will use two scientific instruments to map the sky.

PHOTO: AFP

So how will Euclid try to spot things that cannot be seen? By searching for their absence.

The light coming from billions of light years away is slightly distorted by the mass of visible and dark matter along the way, a phenomenon known as weak gravitational lensing.

“By subtracting the visible matter, we can calculate the presence of the dark matter which is in between,” Dr Racca said.

While this may not reveal the true nature of dark matter, scientists hope it will throw up new clues that will help track it down in the future.

For dark energy, French astrophysicist David Elbaz compared the expansion of the universe to blowing up a balloon with lines drawn on it.

By “seeing how fast it inflates”, scientists hope to measure the breath – or dark energy – making it expand.

A presentation of the Euclid spacecraft in Cannes, France, in February.

PHOTO: AFP

‘Goldmine’

A major difference between Euclid and other space telescopes is its wide field of view, which takes in an area equivalent to two full moons.

Project scientist Rene Laureijs said that this wider view means Euclid will be able to “surf the sky and find exotic objects” like black holes that the Webb telescope can then investigate in greater detail.

Beyond dark energy and matter, Euclid’s map of the universe is expected to be a “goldmine for the whole field of astronomy”, said Dr Yannick Mellier, head of the Euclid consortium.

Scientists hope Euclid’s data will help them learn more about the evolution of galaxies, black holes and more.

The first images are expected once scientific operations start in October, with major data releases planned for 2025, 2027 and 2030.

The €1.4 billion (S$2 billion) mission is intended to run until 2029, but could last a little longer if all goes well. AFP, REUTERS