Doubts over climate funding as donors squeeze aid

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

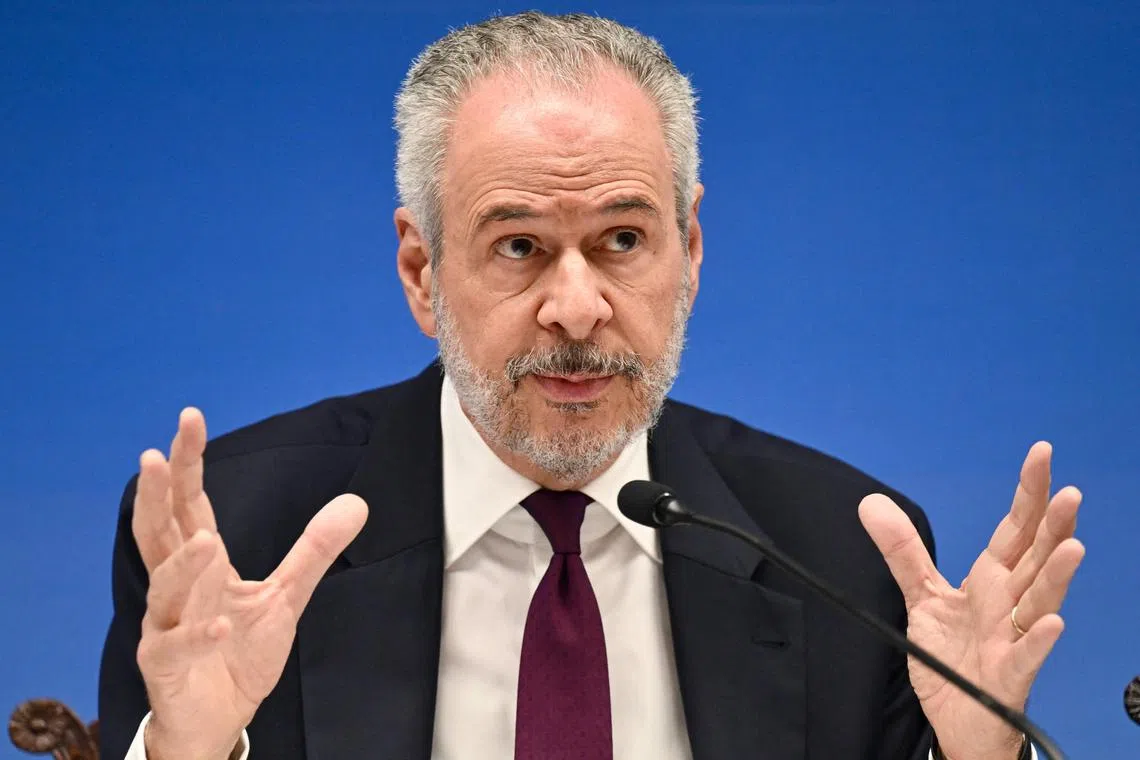

Brazilian ambassador Andre Correa do Lago is president of 2025's COP30, which Brazil is hosting.

PHOTO: AFP

PARIS – There are growing doubts about a pledge by rich nations to provide more climate finance to poorer nations, as foreign aid budgets are slashed and the US guts environmental spending.

Richer nations committed at the UN COP29 summit in November 2024

Since then, President Donald Trump has frozen US contributions to the global pot

Britain, meanwhile, has trimmed overseas aid to raise defence spending, following a slew of similar cuts by climate-friendly governments in Europe.

Diplomats and analysts say it remains unclear where the axe might fall, but there are fears that money earmarked for climate finance could be on the chopping block.

Dr Laetitia Pettinotti, a climate economist from think-tank ODI Global, told AFP that signs are not good and cuts could be expected.

“It’s really hard to see where the money is going to come from,” she said.

Difficult road

With the United States halting its climate action, expectations have fallen largely on the European Union, historically the third-largest producer of greenhouse gases, and the biggest contributor to climate finance.

But the 27-nation bloc is under budget strain, facing US tariffs and trying to ramp up military spending to defend itself and Ukraine

Recent elections, meanwhile, have seen right-wing populists hostile to climate policies make gains across the continent.

France, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Britain have all announced recent aid cuts as economic and security priorities shift and budget pressures take hold.

The EU “needs to find a new way to prioritise its limited resources, for very legitimate reasons”, said Mr Li Shuo, a climate analyst at the Asia Society Policy Institute in Washington.

“This will make the climate finance discussion very difficult.”

‘Worrying trends’

Azerbaijan, which hosted the COP29 summit where the US$300 billion deal was brokered, is seeking reassurances at a two-day meeting of climate negotiators in Tokyo that ends on March 13.

Mr Yalchin Rafiyev, the country’s top climate diplomat, said he would be asking developed nations if the cuts impacted money “they were thinking or planning to allocate for climate or not”.

“We are not sure yet. There was not any concrete kind of climate fund cuts that we have heard from any of the parties. There was only some worrying trends,” he told AFP.

He added: “We are opposed to any kind of action that can reduce the funding for climate action.”

Brazil, which is hosting 2025’s COP30 summit, said it was exploring ways to raise the enormous sums needed for developing countries to wean off fossil fuels and adapt to global warming.

According to independent experts, these countries – excluding China – will require US$1.3 trillion a year in outside assistance by 2035 to meet their climate needs.

Under the Paris Agreement, developed countries – those most responsible for global warming to date – are obligated to pay climate finance, but other countries do make their own voluntary contributions.

“Climate finance for developing countries was already insufficient, but the recent cuts to foreign aid budgets represent a renewed challenge,” the COP30 presidency said in a written statement to AFP.

‘Not looking good’

Donors have struggled to meet their climate finance pledges at the best of times, even for commitments well below the US$300 billion pledged in 2024.

Developed nations provided about US$116 billion in 2022, the latest year for which official climate finance figures are available from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The US provided about 10 per cent of that money. Mr Trump’s spending freeze means other contributors will have to make up the difference.

Other ways to possibly plug the shortfall – such as greater lending from multilateral development banks like the World Bank – are also in doubt.

“You’re going to hear more and more that there simply isn’t money out there to fill up such a big pot... It’s not looking good,” Ms Avantika Goswami, climate change lead at the Centre for Science and Environment in India, told AFP. AFP