CO2 emissions hit record in 2024, warming limit could be breached by 2030: Study

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

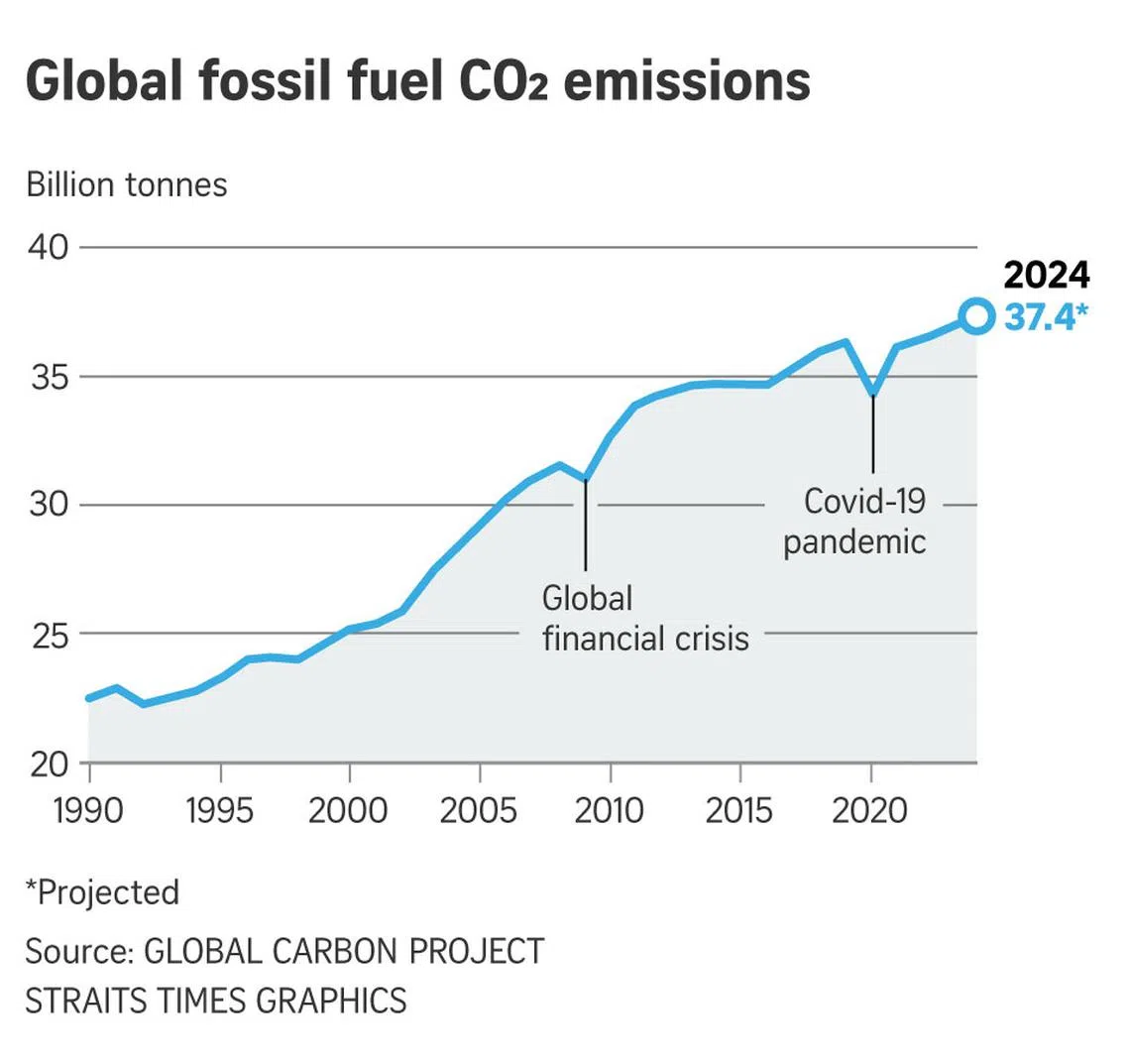

The study predicts CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels will increase by 0.8 per cent from 2023 to reach 37.4 billion tonnes in 2024.

PHOTO: REUTERS

SINGAPORE – Global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from burning fossil fuels are predicted to reach a record in 2024, setting the world on course to breach a key climate change temperature limit by 2030, a study released on Nov 13 found.

The study by the Global Carbon Project, an international scientific consortium, predicts CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels will increase by 0.8 per cent from 2023 to reach 37.4 billion tonnes in 2024.

Despite progress in clean energy investment globally, especially record investment in China, growth in natural gas and oil use is the main driver pushing up global fossil emissions.

Emission growth in 2024 indicates that “the massive investment in renewable energy is still not big enough to meet the increase in energy demand, let alone to start curving down global emissions towards the net-zero emission target”, said Dr Pep Canadell, executive director of the Global Carbon Project. He was referring to the global goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

Deforestation, wildfires and peatland degradation are also adding extra CO2 to the atmosphere and heating up the planet, said the analysis.

Released during the COP29 United Nations climate talks in Baku, Azerbaijan, the study comes after a year marked by extreme weather events, from back-to-back hurricanes in Florida deadly floods in Spain

Emissions are predicted to decrease in the European Union (dropping 3.8 per cent from 2023) and in the US (0.6 per cent), mainly on falling coal use. Burning coal is the single largest source of CO2 emissions from human activity.

In China, which is responsible for about a third of all carbon emissions from human activity, CO2 pollution is expected to rise by 0.2 per cent in 2024, compared with 4.9 per cent in 2023.

For India, emissions are predicted to rise 4.6 per cent in 2024, compared with 2023’s increase of 8.2 per cent. India is the No. 3 emitter after China and the US.

“India’s economy continues to grow strongly. Its services sector, which requires less energy, and its growing renewable energy capacity go some way to explain the lower energy intensity of its economy. However, coal emissions continue to grow robustly,” Dr Canadell said.

A slowdown in the construction sector, which means fewer emissions from the production of cement, and the record additions of wind and solar energy capacity limited China’s emissions growth, he added.

CO2 pollution from international aviation and shipping, which is about 3 per cent of global emissions, is projected to increase by 7.8 per cent in 2024 over 2023, but remain just below the 2019 pre-pandemic level.

Carbon emissions from fossil fuels are responsible for about 90 per cent of all CO2 pollution from human activity. Coal, oil and gas are used to generate electricity, for transport and industry, and to make chemicals and products such as plastics, underscoring how dependent the global economy is on the fuels.

But green energy investment is slowly changing this.

The International Energy Agency has predicted that US$2 trillion (S$2.7 trillion) will be spent in 2024 on clean technologies such as renewables, electric vehicles and nuclear power – double the amount spent on coal, gas and oil.

While a rise of 0.8 per cent might not seem much (fossil fuel CO2 emissions rose by 1.4 per cent in 2023), adding CO2 emissions stokes global warming and puts the planet even further off course in dialling back the dangers from climate change.

Greenhouse gas emissions must peak before 2025 at the latest and fall by 43 per cent by 2030 from 2019 levels if global warming is to be limited to around 1.5 deg C above pre-industrial levels, the UN’s top climate science body says.

It says busting 1.5 deg C – a key guardrail under the UN’s 2015 Paris Agreement climate pact – risks far more extreme weather events and faster sea-level rise.

The world has already warmed about 1.3 deg C, and the analysis says that if total CO2 emissions continue at current levels, the 1.5 deg C global average warming limit could be exceeded in six years.

There is good news.

Dr Canadell said a growing number of countries have succeeded in reducing their fossil fuel CO2 emissions, or slowing down their growth.

For example, fossil fuel CO2 emissions fell in 22 countries – representing 23 per cent of global fossil fuel CO2 emissions – during the past decade (2014 to 2023), while their economies grew.

And economies are becoming more efficient with declining CO2 emissions per unit energy.

Emissions from land use change, such as deforestation, were predicted to reach 4.2 billion tonnes in 2024, similar to 2023’s level. This is in addition to the 37.4 billion tonnes from burning fossil fuels.

Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo together contribute 60 per cent of the global net land-use change CO2 emissions, the study said. Most of these emissions come from deforestation land management, including wood harvest as well as peat drainage and peat fires.

“We are clearly getting closer and closer to the peak of fossil fuel CO2 emissions,” Dr Canadell said.

“However, it is likely to be bumpy before we can confirm a global peak, with the next big question being: How long is it going to take before emissions start declining towards net zero, as we urgently need?”

The analysis, in its 19th year, is produced by more than 100 scientists who dissect huge amounts of energy data and estimates of what happens to all the CO2 when it is in the atmosphere. For instance, the analysis looks at the earth’s natural carbon sinks, such as forests, soils and oceans, which absorb large amounts of CO2.