Chikungunya: A debilitating virus surges globally as mosquitoes move with warming climate

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Chikungunya is transmitted by the same species of mosquitoes behind Zika and dengue fever.

PHOTO: ST FILE

GENEVA – A mosquito-borne virus that can leave infected people debilitated for years is spreading to more regions of the world, as climate change creates new habitats for the insects that carry it.

More than 240,000 cases of the virus, chikungunya, have been reported around the world so far in 2025, including 200,000 cases in Latin America and 8,000 in China

The Chinese authorities have launched an urgent effort to try to stifle the virus with public health measures that evoke the response to Covid-19.

Chikungunya is not circulating in the United States or Canada, but cases have been reported in France and Italy. The disease is endemic in Mexico.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) is warning that current transmission patterns resemble a global outbreak

Although it is rarely fatal, chikungunya causes excruciating and prolonged joint pain and weakness.

“You have people who were working, with no disabilities, and from one day to the next, they cannot even type on a phone, they can’t hold a pen, a woman cannot even hold a knife to be able to cook for her family,” said Dr Diana Rojas Alvarez, who leads chikungunya work at the WHO. “It really impacts quality of life and also the economy of the country.”

How dangerous is chikungunya?

Chikungunya is a virus from the same family as Zika and dengue fever.

Two different species of mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, transmit chikungunya.

Between four and eight days after a bite, a person can develop symptoms, including fever, joint pain and a rash.

Unlike dengue and Zika infections, the majority of which are asymptomatic, chikungunya sickens most people it infects.

In rare instances, chikungunya can kill young children and older adults.

“Fatality levels are low, but we really care about chikungunya because it leaves people with months or potentially years of debilitating pain,” said Dr Scott Weaver, an expert and the scientific director of the Galveston National Laboratory in Texas.

He added: “That has not only an individual toll but also a social one, with strain on healthcare systems, economic impact, the demand on caregivers, a lot of things.”

Chikungunya is often misdiagnosed as dengue, which causes the same symptoms at first.

Dengue symptoms usually clear up in a week or two; chikungunya symptoms become chronic in as many as 40 per cent of people infected, with debilitating joint pain lasting for months or years.

Who is at risk?

By the end of 2024, transmission of the virus had been reported in 199 countries, on every continent except Antarctica.

The WHO estimates that 5.6 billion people live in areas where the mosquitoes that transmit the virus can live.

These mosquitoes are daytime biters, feeding on people who are at work, at school or on a bus.

Climate change is driving the spread of chikungunya-carrying mosquitoes in two ways.

A warmer, wetter world provides more suitable habitat. And extreme weather events can cause more breeding in floods – or displace people, who cluster in areas with poor water and sanitation supply.

The Aedes albopictus mosquito has markedly expanded its presence in Europe in recent years: The insect has been found in Amsterdam and Geneva. In South America, Aedes aegypti carries the virus and thrives in low-income neighbourhoods in rapidly growing cities with patchy water systems.

“In the US, I don’t think we’re going to see massive outbreaks of chikungunya” because people in warm areas use air-conditioning and spend a lot of time indoors, Dr Weaver said.

“But in places like China and the Southern Cone of South America, the warming temperatures are going to have a big impact because people don’t stay inside with air-conditioners in their houses or their workplaces,” he said. “They don’t even like to screen their windows in many parts of Asia and South America.”

A public health worker spraying insecticide at a housing estate in Hong Kong.

PHOTO: REUTERS

People seem to become immune to chikungunya after an infection and so, if it sweeps through an area, it can be a couple of decades before there are enough immunologically vulnerable people to sustain another outbreak.

But in places such as India and Brazil, populations are so large that the virus is circulating constantly.

Many countries in Africa that did not have circulating chikungunya, such as Chad and Mali, have reported cases in the past few years.

Is there a vaccine?

There are two vaccines for chikungunya, but they are produced in limited quantities for use mainly by travellers from industrialised countries.

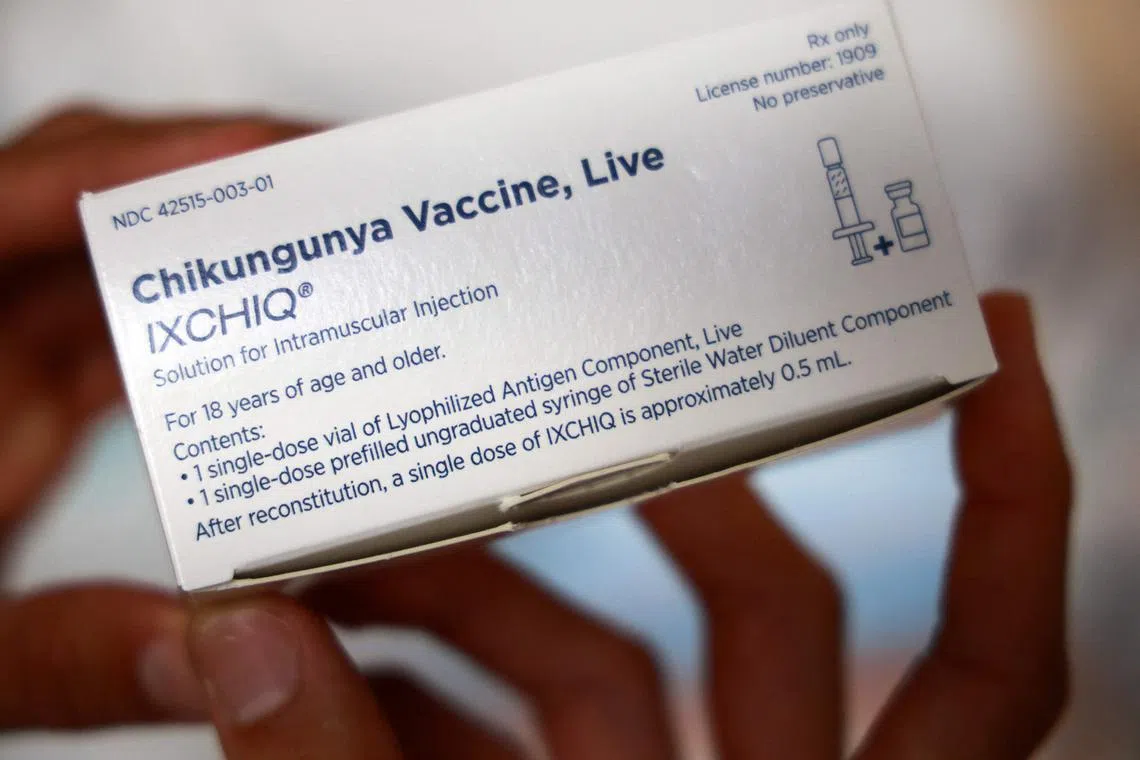

The newest vaccine,

Brazil’s Butantan Institute is working on making a lower-cost version of another vaccine.

Neither vaccine currently has the kind of WHO recommendation that might lead to accelerated development of an affordable product.

Doing a clinical trial of the kind the agency requires is difficult: Chikungunya outbreaks happen so fast that they are over before the research can begin.

Dr Alvarez said the WHO’s vaccine committee was reviewing chikungunya outbreak data to consider options for a possible recommendation.

A box of Ixchiq chikungunya vaccine at a pharmacy on France’s overseas Indian ocean island of La Reunion, in L’Etang Sale.

PHOTO: AFP

What else can be done?

The best protection against chikungunya is not to get bitten.

The next step is to reduce mosquito breeding sites. In China, public health officials are going house to house to look for stagnant water.

Surveillance for chikungunya is still weak.

Dr Alvarez said the WHO was trying to untangle how much of the current surge was new cases and how much was transmission that was already occurring but poorly tracked or reported.

There is a molecular diagnostic test that screens for Zika, dengue and chikungunya at the same time, but more countries need to adopt it.

Disease surveillance globally has been weakened by the abrupt cuts in funding from the US government, which was supporting much of this work in low-income countries.

Is this a new virus?

Chikungunya was first identified in Tanzania in the 1950s, and caused sporadic outbreaks in Africa and Asia in the next decades.

But the virus did not attract much attention from public health specialists until 2004. That year, an outbreak in Kenya spread to La Reunion, a French territory in the Indian Ocean. There, chikungunya raged through the population: One-third of the people on the island were infected.

That same strain of the virus made its way to South Asia, and caused huge outbreaks in India from 2005 to 2007. And from there travellers took chikungunya around the world.

By late 2013, the virus had made its way to the Caribbean and once again began to tear through a population that lacked immunity.

There were 1.8 million reported infections in the region by the end of 2015.

Chikungunya then made its way down through South America – and a new strain from Angola was introduced to Brazil at the same time – and the two have been circulating since then.

Chikungunya cases in South America have risen steadily since 2023, alongside a surge in dengue cases. NYTIMES