Primordial sea creature with spiky claws unearthed in Canada

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Follow topic:

WASHINGTON (REUTERS) - A fossil site in the Canadian Rockies that provides a wondrous peek into life on Earth more than half a billion years ago has offered up the remains of an intriguing sea creature, a four-eyed arthropod predator that wielded a pair of spiky claws.

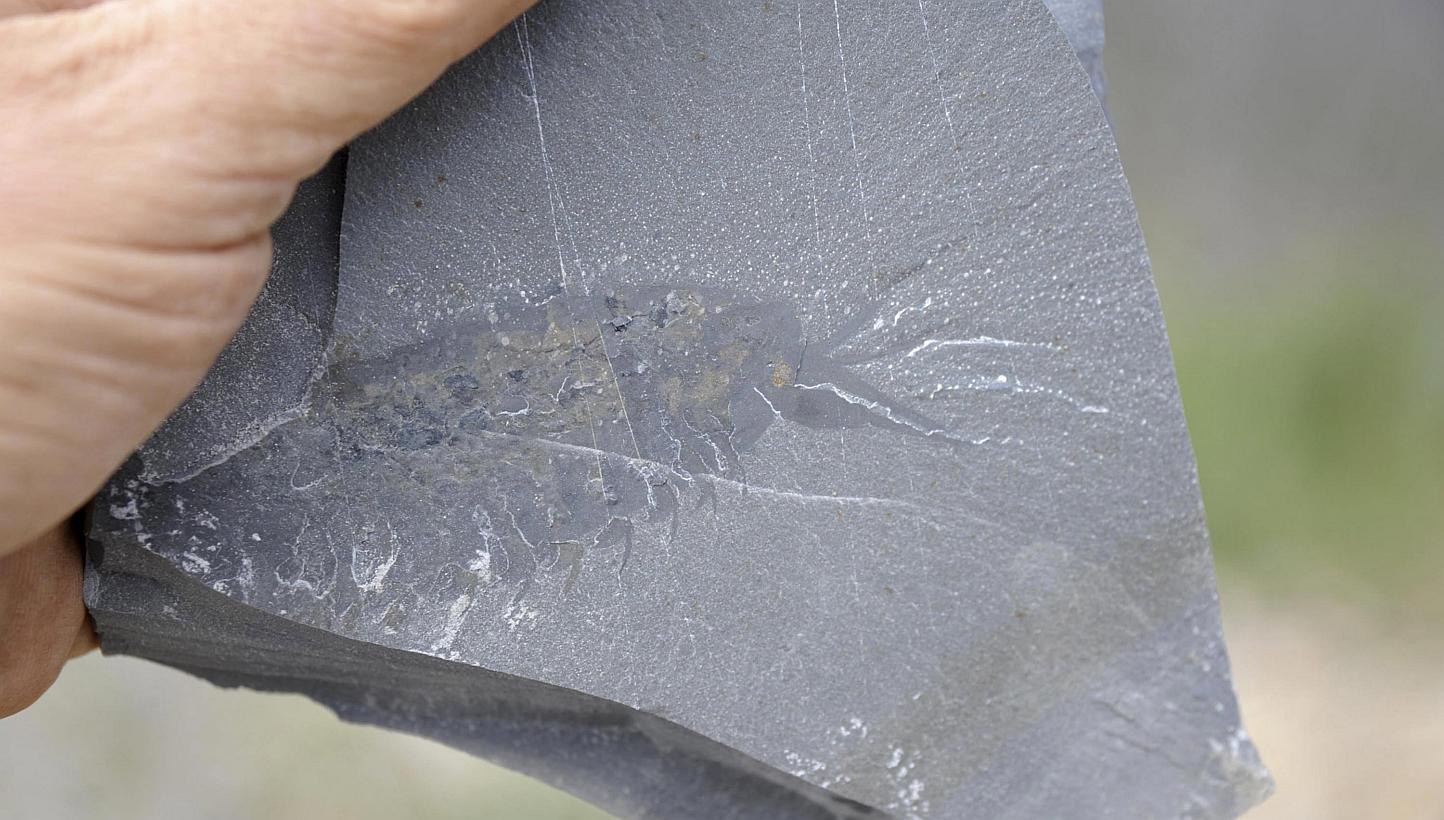

Scientists said on Friday they unearthed nicely preserved fossils in British Columbia of the 508 million-year-old animal, named Yawunik kootenayi, that looked like a big shrimp with a bad attitude and was one of the largest predators of its time.

Including its claws, Yawunik measured about 22.5cm long. That may not sound impressive, but most creatures at the time were much smaller.

The fossil beds in Kootenay National Park where it was found were in a previously unexplored area of the Burgess Shale rock formation that for more than a century has yielded exceptional remains from the Cambrian Period, when many of the major animal groups first appeared.

Yawunik, whose name honors a mythical sea monster in the native Ktunaxa people's creation story, was a primitive arthropod, the highly successful group that includes shrimps, lobsters, crabs, insects, spiders, scorpions, centipedes and millipedes.

A capable swimmer and active predator, it possessed rows of spikes along its large frontal claws, a highly developed sensory system comprised of two pairs of eyes and elaborate antennae, and a body divided into 17 segments.

"The new fossils show clearly that these primitive arthropods were sophisticated, fearsome predators," said paleontologist Robert Gaines of California's Pomona College. "Our vertebrate ancestors had not yet developed bones or jaws, and remained humble bottom feeders."

Cedric Aria, a doctoral candidate at the University of Toronto's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, said more than a hundred Yawunik fossils have been unearthed. "You could indeed say that it looks like a big shrimp whose antennae would also be made of large claws," Aria said, whose research appeared in the journal Palaeontology.

Two large grasping appendages at the front of the head were capable of a wide range of backward-forward motion. The spikes on its claws helped it grasp prey.

Elaborate antennae on these appendages allowed it to sense its environment, perhaps not only by feel but by detection of chemical traces, effectively smelling.

"I've been working with Burgess Shale-type fossils in the field for 15 years, and Yawunik is without a doubt the most exciting and the most beautiful fossil I have ever seen come out of the ground," Gaines added.