18 football fields of tropical forest lost every minute in 2024 largely due to fires: Study

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

The areas affected by fires in the Brasilia National Forest region on Sept 4, 2024. More than half of the tropical forest loss that year occurred in fire-scorched Brazil and Bolivia.

PHOTO: AFP

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE – Fires triggered unprecedented global forest loss in 2024, driven by a dangerous cocktail of drought linked to climate change, extreme heat and agricultural expansion in the tropics, a study released on May 21 showed.

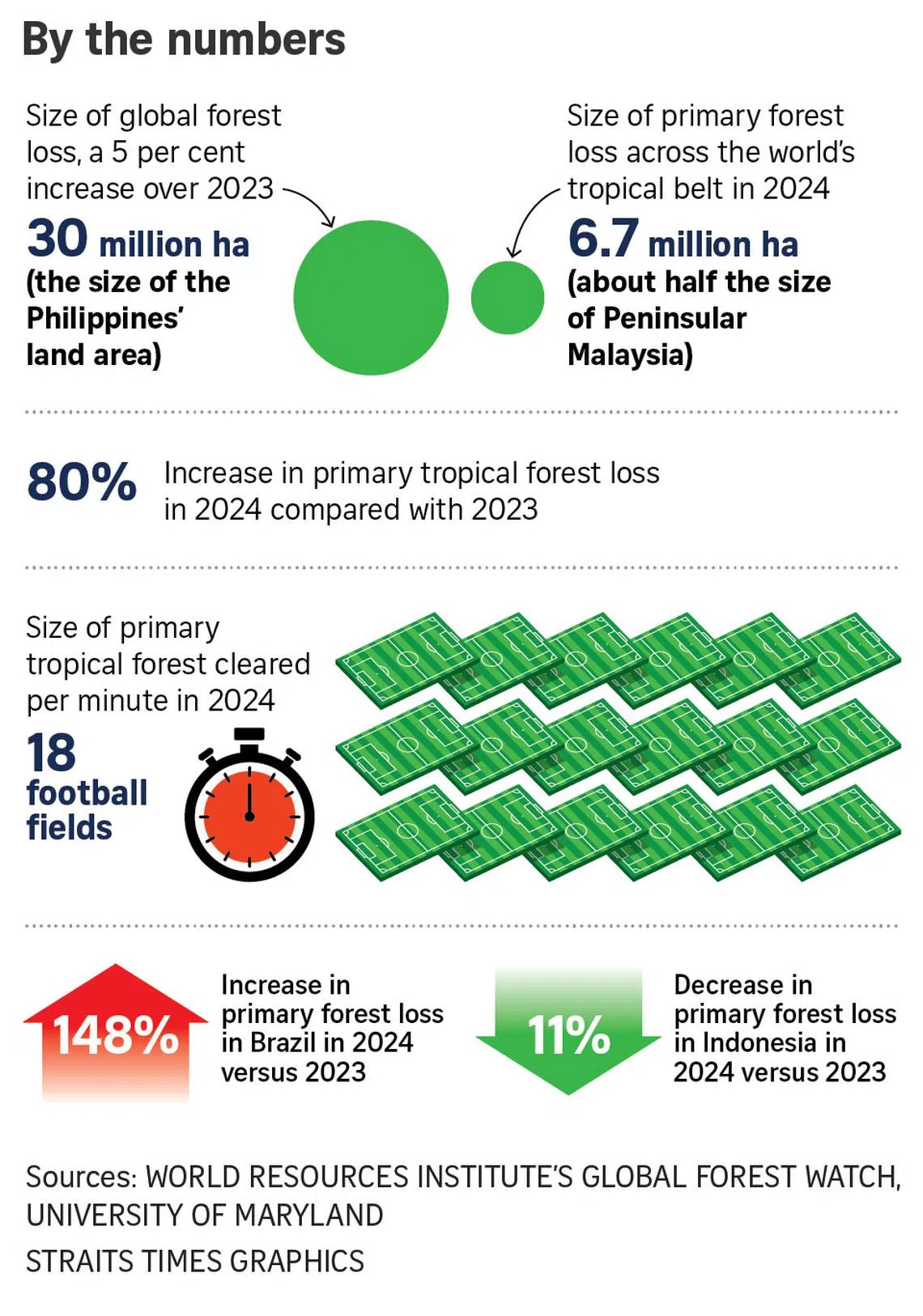

Global tree cover loss reached 30 million ha in 2024, up 5 per cent from 2023.

But it is across the tropics where the 2024 data is especially worrying, said the authors of a study conducted by the University of Maryland and made available on the World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Global Forest Watch platform.

A record 6.7 million ha of tree cover in tropical primary forests was lost – that is about half the size of Peninsular Malaysia and nearly double 2023’s loss of 3.7 million ha. That magnitude of loss is equivalent to about 18 football fields disappearing every minute.

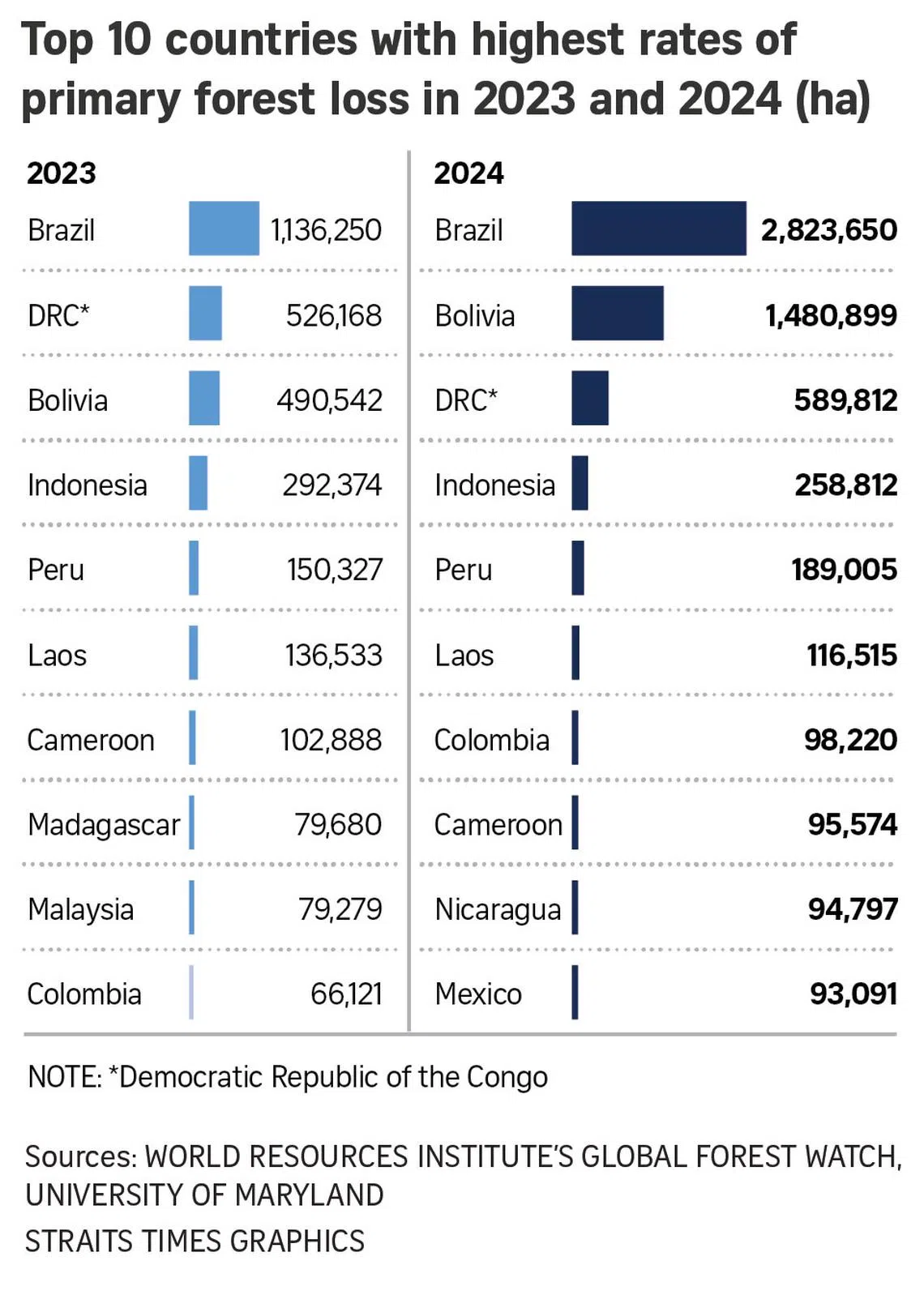

More than half of the tropical forest loss in 2024 occurred in fire-scorched Brazil and Bolivia. Tree cover loss also rose across parts of Central Africa.

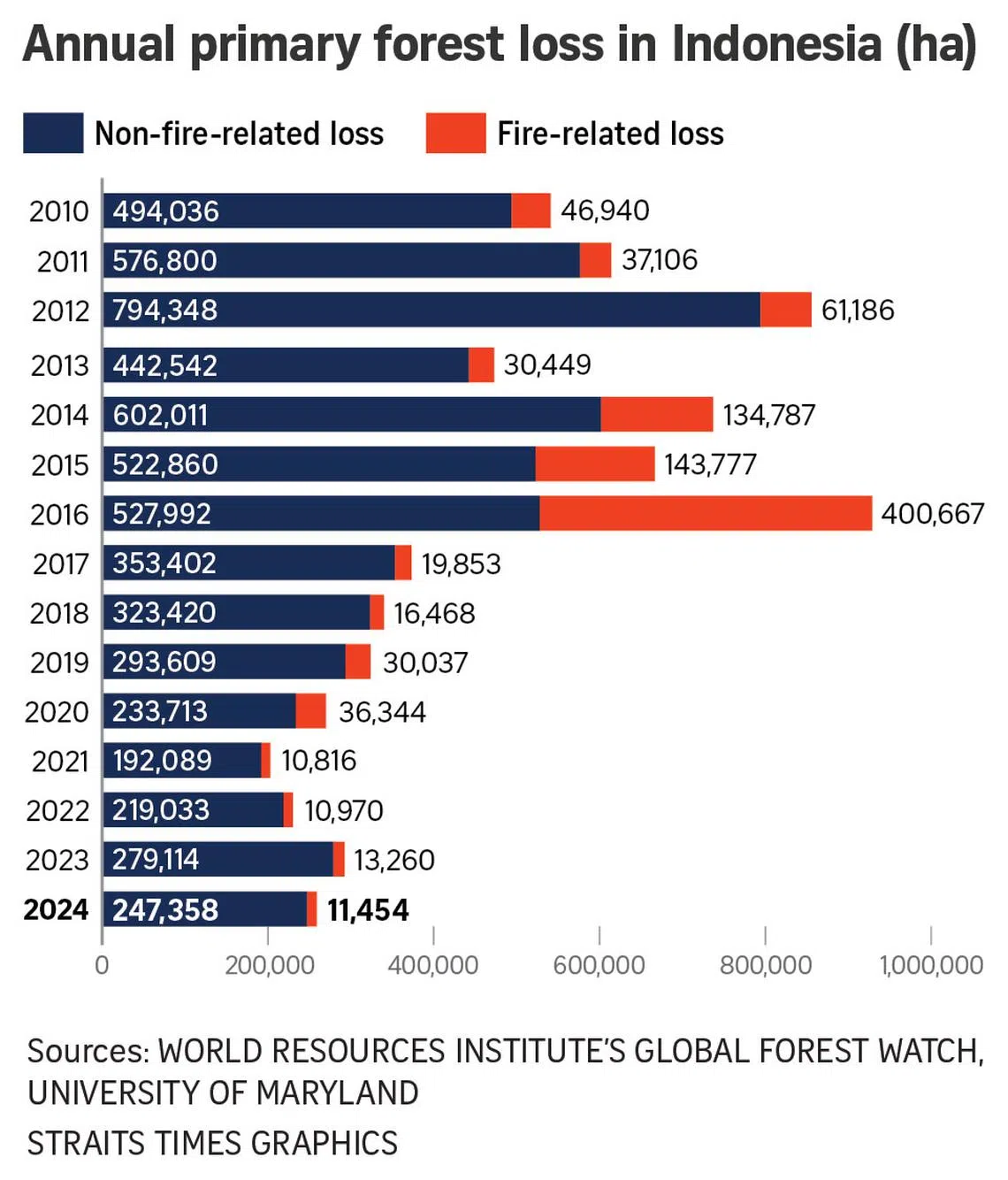

But there was better news for Indonesia and Malaysia: Tree cover loss fell in both nations.

In Indonesia, late monsoon rains and fire prevention efforts by local communities and agribusinesses helped reduce the risks. In Malaysia, government efforts to cap plantation areas and toughen forest laws, plus corporate commitments to reduce deforestation, are paying off, the authors said.

“The 2024 numbers must be a wake-up call to every country, every bank, every international business. Continuing down this path will devastate economies, people’s jobs and any chance of staving off climate change’s worst effects,” said Ms Elizabeth Goldman, a senior researcher at Global Forest Watch, during a media briefing for the study.

The study uses data from the University of Maryland’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery (Glad) laboratory.

Tropical forests are critical for humanity, especially local communities – they act as water stores for rivers and clouds, soak up huge amounts of carbon dioxide, contain the richest amount of biodiversity on land and are an important source of raw materials for key medicines.

Scientists and wildfire experts have been warning for years that hotter weather and longer, more intense droughts are fuelling more extreme fire seasons.

That tallies with 2024’s tree loss data: The fires occurred during the warmest year on record with hot, dry conditions largely caused by climate change and the El Nino weather pattern.

In a rare occurrence, fires burned simultaneously in the tropics and in the boreal forests of the Northern Hemisphere, worsening air pollution and spewing huge amounts of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas.

Forest fires globally in 2024 released 4.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide – or more than four times the emissions from all air travel in 2023 – further fuelling climate change.

Fires burned five times more tropical primary forest in 2024 than in 2023 – in total, fires were the main driver for half of all primary forest loss in 2024, followed by agriculture at 29 per cent.

Brazil topped the list of forest losses in tropical countries, totalling 2.8 million ha, up 148.5 per cent from 2023, driven by drought and one of the nation’s worst fire seasons. Two-thirds of Brazil’s 2024 loss was fire-related.

Bolivia came in second with primary forest loss jumping by 201 per cent in 2024 to 1.48 million ha, with nearly two-thirds of it due to fires, which were mostly started to clear land for industrial-scale farming.

Primary forest loss also rose in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which has one of the world’s largest areas of tropical rainforests, in part due to fires and conflict.

But primary forest loss fell in Malaysia in 2024, dipping 13 per cent to 68,851ha, an area slightly smaller than Singapore. In Indonesia, primary forest loss fell by 11 per cent from 2023 to 258,812ha.

While Indonesia’s tree cover loss numbers have maintained a trend of sharply lower deforestation since 2017, there are concerns the policies of the administration of President Prabowo Subianto could change the picture.

“This new administration with policies that are pro-energy independence, pro-food independence, you likely will see backsliding,” said Professor Matt Hansen, co-director of the University of Maryland’s Glad laboratory, at the media briefing.

He was referring to efforts to ramp up the creation of giant food estates in Indonesia, as well as to boost the use of palm oil as a biofuel and biomass, such as wood pellets, for energy.

Noting Indonesia’s improved track record under the previous administration of Mr Joko Widodo, Prof Hansen said that changes in government in Indonesia and elsewhere can lead to “yo-yoing” of political ambitions and forest protection policies.

In 2021, more than 140 countries signed the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration, promising to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. But the study’s latest figures show this target is way off course.

Dr Arief Wijaya, managing director of WRI Indonesia, agreed that some of Mr Prabowo’s policies, such as large-scale food estates, could lead to forest loss if not properly implemented. But he noted the country’s efforts to sharply reduce deforestation in recent years.

He said the Indonesian government’s goal to set aside 12.7 million ha of forest land for a social forestry programme for communities could lead to local protection from fires and illegal clearing. The move could also strengthen law enforcement, such as the revocation of inactive forestry concessions.

The Prabowo administration is also trying to build up a carbon credit market that aims to protect large areas of forests in return for climate benefits, capitalising on the huge potential of forests to trap carbon dioxide from the air and acting as a brake on climate change, he noted.

Still, conservationists fear large food estates, such as the one being created in Merauke in South Papua province covering more than 1 million ha, will lead to massive deforestation and conversion of carbon-rich peatlands.