Single jab of modified gene could be next big thing in controlling stray cat numbers

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

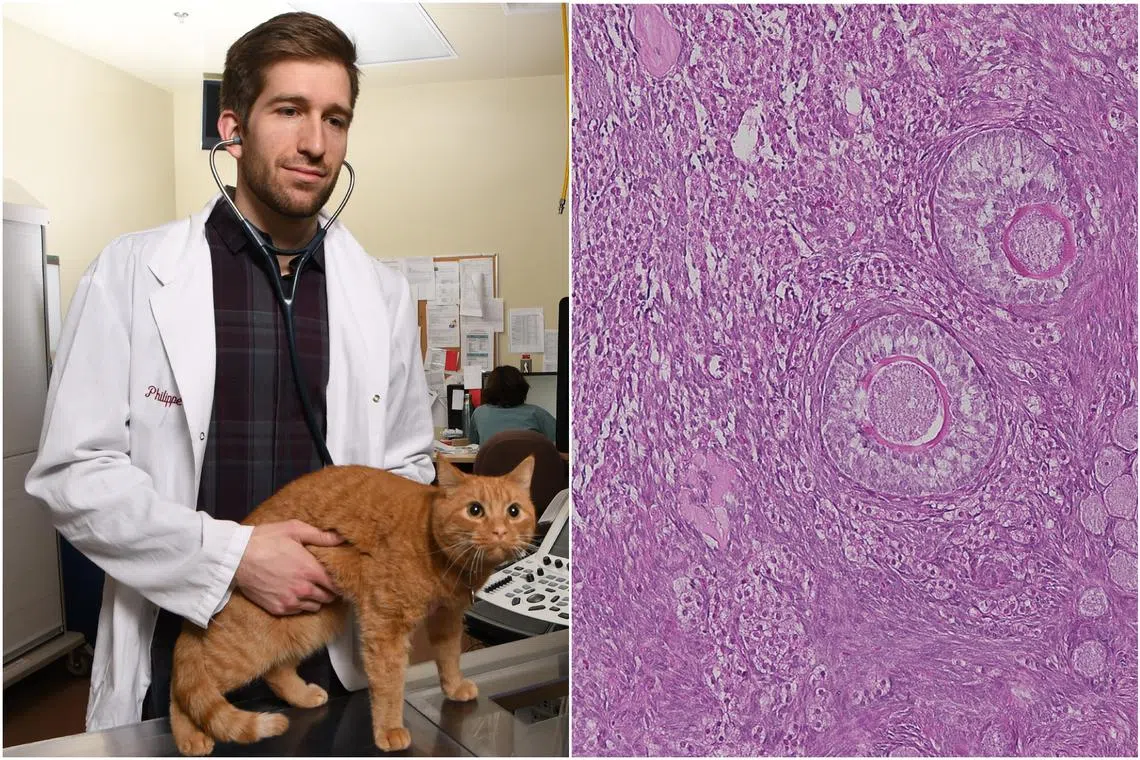

Mr Philippe Godin (left), co-author and veterinarian in the research team. On the right are microscopy images of cat ovarian follicles.

PHOTOS: MARCO LANGLOIS, CINCINNATI ZOO, PHILIPPE GODIN

SINGAPORE – Researchers have come up with what could be a revolutionary form of feline contraception that is cheap, painless and surgery-free.

Following a chance discovery while the scientists were studying ovarian cancer in people, the team developed an injection to hormonally shrink cats’ ovaries, rendering them sterile.

The research by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, the Centre for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife in Cincinnati and their collaborators was published in the journal Nature Communications in June.

Their work hinged on the so-called anti-mullerian hormone (AMH), a non-steroidal hormone produced by humans and other mammals that plays a key role in reproductive organ formation in foetuses and, in adult women, controls other hormones that act on the ovaries during a menstrual cycle.

The scientists made their discovery while researching the use of AMH to help protect the fertility of women undergoing cancer treatment, by preserving the number and quality of their eggs before chemotherapy, which can have detrimental effects on ovarian function.

“I noticed that when mice were treated with high doses of AMH, the ovaries appeared to become smaller,” team member David Pepin told The Straits Times.

Ovary shrinkage indicates suppressed growth of egg follicles in the ovaries, effectively preventing ovulation and conception.

“It quickly became apparent that one of the potential applications was in contraception. This led us to try to apply this new technology to the problem of free-roaming cat overpopulation,” said Dr Pepin, associate director and principal investigator of the Paediatric Surgical Research Laboratories at MGH.

Gene therapy, or gene editing, entails modifying or replacing faulty genes in cells – usually to treat or prevent diseases.

The most common method involves the use of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) to act as vehicles, delivering the therapeutic genes into cells – similar to how disease-causing viruses inject their own DNA into cells to produce more virus cells and infect other cells.

AAVs, however, are non-pathogenic, meaning they do not cause disease.

The scientists developed fcMISv2, a modified feline AMH gene based on the genetic information of domestic cats.

This was injected into the rear thigh muscles of several cats, using AAV9 (AAV serotype 9) as the delivery system, as it has a tendency to target or “infect” muscle tissue and is not usually blocked by antibodies in cats.

The team discovered that a single injection caused the muscle cells to start producing AMH continuously.

Cats involved in the study. They did not have any significant adverse effects or develop antibodies to fcMISv2.

PHOTO: CINCINNATI ZOO

AMH levels in the cats were found to be “robust” in the first year but gradually dropped and plateaued in the second year – although the felines’ levels of the hormone were still higher than normal.

The cats also did not suffer any significant adverse effects or develop antibodies to fcMISv2.

Vets and animal-control professionals here said a non-surgical, lifelong contraceptive from a single injection would have many advantages over current procedures.

“Currently to sterilise a stray cat, it first needs to be trapped and sent to the vet for surgery, and its left ear will be ‘tipped’ in order to identify that cat as being already sterilised,” said Dr Teng Yi Wei, a veterinary surgeon at Barkway Pet Health.

“Giving an injection is easier in manpower terms. However, the cost of the injection has to be cheaper than the cost of sterilisation surgery for this to work.”

A non-surgical, lifelong contraceptive from a single injection would have many advantages over current procedures.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF JUDITH TAN

According to the Animal and Veterinary Service, sterilisation reduces the risk of mammary gland tumours, ovarian and uterine cancers, and womb infections in female pets.

Dr Cathy Chan, a veterinarian at The Animal Doctors, said that although the new form of contraception helps to stop reproductive aspects, it may not have the same medical benefits as sterilisation.

“Unless they have evidence to show that the procedure would reduce the cancer risks in the long term – although I doubt so as it’s a new technology, it would be too early to say,” she added.

More studies still need to be done to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of the technology despite successes in pre-clinical trials.

The team plans to conduct clinical trials in the United States with the Food and Drug Administration, and hopes that this technology will be available as an approved product to control cat overpopulation across the world – which Dr Pepin said could take more than five years.