‘Brain in a dish’ learns to play Pong, offers a new way to discover drugs

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

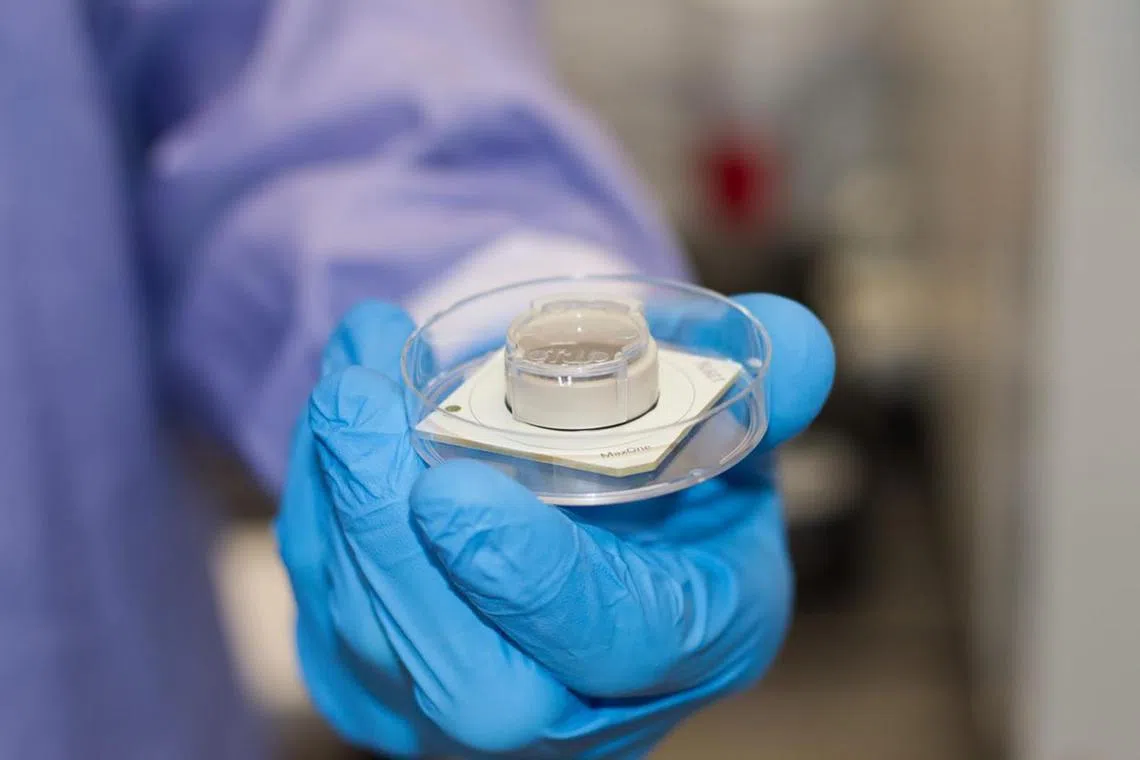

A sample of Cortical Labs’ cell-powered chip, which reads electrical signals emitted from cells in a Petri dish.

PHOTO: CORTICAL LABS

SINGAPORE - Computer chips based on lab-grown brain cells could one day power artificial intelligence (AI) tools to discover new drugs without generating as much heat as normal computers.

That is the future imagined by Singapore-headquartered start-up Cortical Labs, which received a US$10 million (S$13.4 million) investment from venture capitalists to commercialise its patented biological intelligence operating system and release a run of prototypes by 2024.

The funding round was led by billionaire Li Ka-Shing’s Horizons Ventures. The Hong Kong venture capital firm has put its money in AI projects including DeepMind, which famously beat a human at the game Go. Other investors include Australia’s leading venture capital fund Blackbird Ventures, the venture capital arm of the United States Central Intelligence Agency’s In-Q-Tel, and US-based LifeX Ventures.

The funding will help four-year-old Cortical Labs commercialise a new computer system to help discover drugs and other AI applications, founder and chief executive Hon Weng Chong, 35, told The Straits Times.

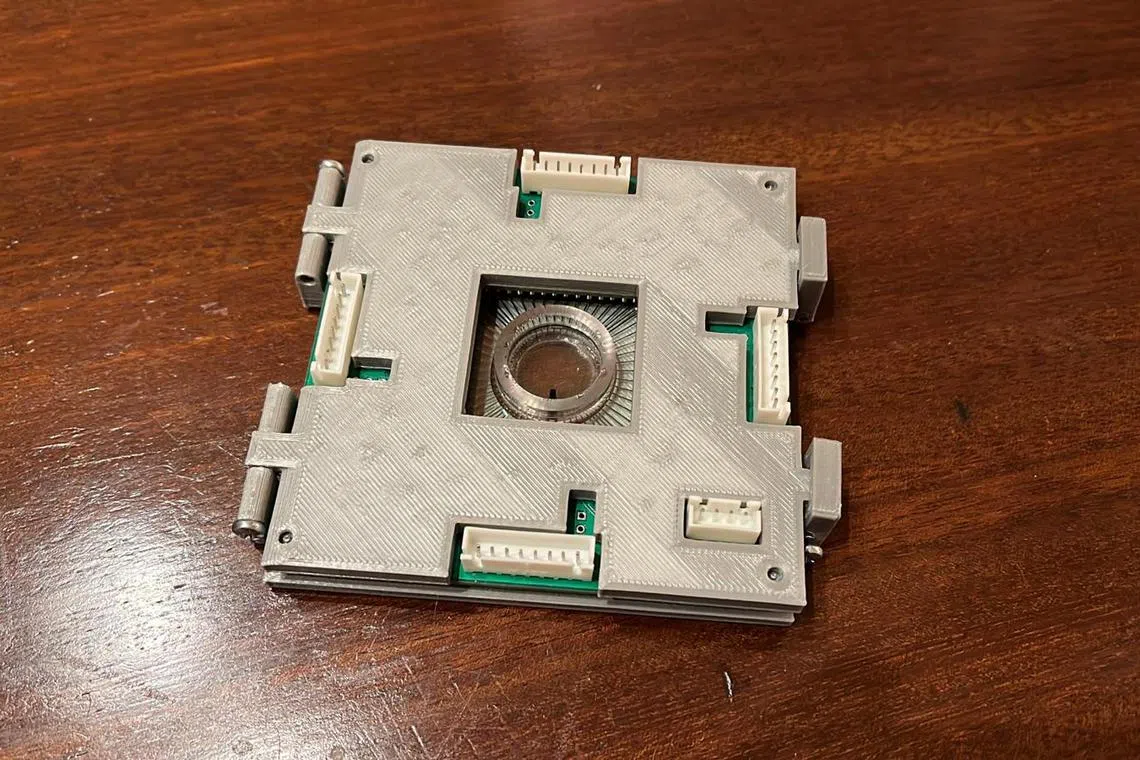

Called DishBrain, the lab’s cell-powered chip comprises neurons cultivated from stem cells and grown on a series of microelectrodes in a petri dish. The system stimulates the cells with electrical signals, and also records the electric charges from the neurons themselves.

Neurons are cells that transmit information within the brain, and between the central nervous system and the rest of the body via electrical or chemical signals.

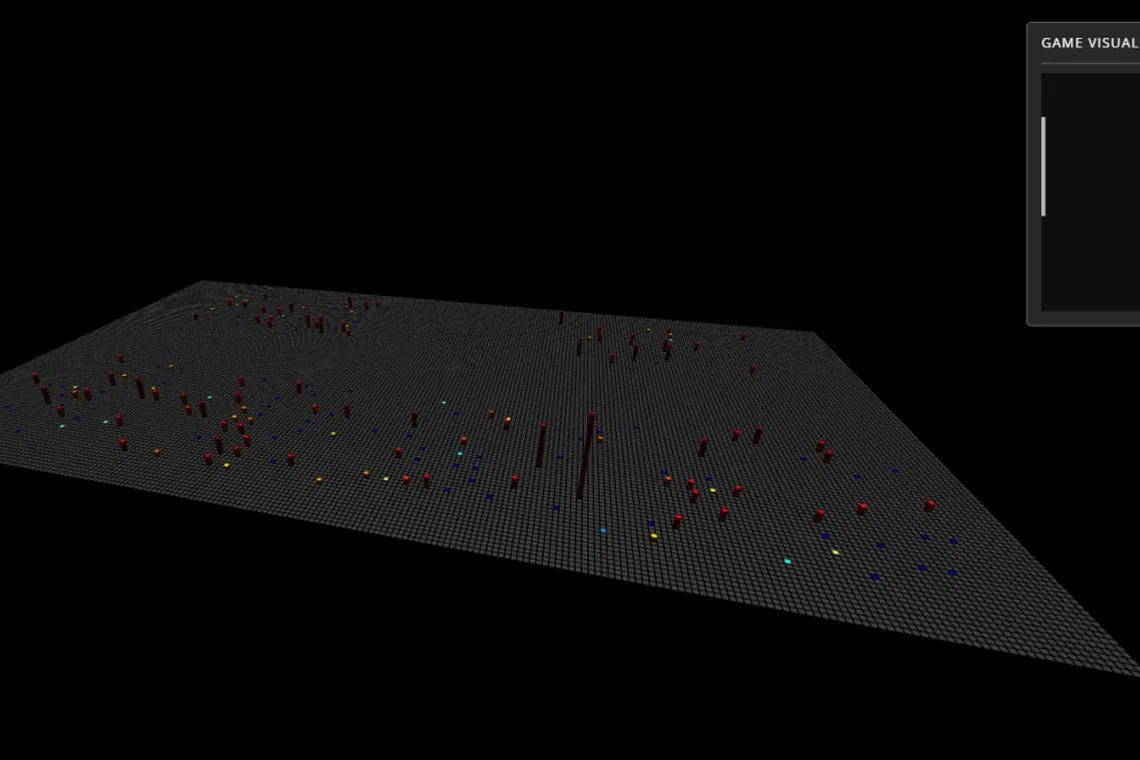

In a study published in scientific journal Neuron last December, Cortical Labs detailed how the neurons could be manipulated by electric charges to generate computing power in real time – when it learnt to play the retro video game Pong in five minutes.

In a simulation of the table tennis-like game, a prototype of the DishBrain was plugged into a computer that sent electric signals to the neurons to indicate where the ball was relative to the paddle. An electric pulse indicated a successful return of the ball. An erratic series of pulses signalled a miss.

The cells learnt the rules of the game by recognising patterns in the pulses, said the researchers.

Or, as Dr Hon put it: “The neurons in the dish were able to organise themselves to play the game.”

Cortical Labs founder and chief executive Hon Weng Chong.

PHOTO: CORTICAL LABS

And as the mini-brain understood the rules of the game and learnt from its mistakes, each rally became longer.

This marks the earliest known breakthrough in terms of a mini-brain plugged into a computer to perform tasks in a program, and it could eventually perform tasks beyond gaming.

The computer also paves the way for a new way to discover drugs. Testing computerised cells in a dish can produce more realistic results compared with traditional algorithms, allowing researchers to gather more data on how cells react to new drugs, said the researchers.

A visualisation of cells learning to play the video game Pong by receiving cues from computer chips read through pulses.

PHOTO: CORTICAL LABS

Bio-computers are trained to perform tasks through recognising patterns, just as cells learn to respond to their environment.

The company’s early buyers are from the biotech industry, who will test the development of new drugs and disease models using the mini-brains, drawing from their ability to react like an organism, without the need for animal testing, said Dr Hon, who is based in Australia.

The company plans to eventually open data centres with cell-powered chips. As the neurons power the computer processing, the chips will not generate heat, unlike normal data centres which need to be cooled, said Dr Hon.

Cortical Labs’ chip, which reads electrical signals emitted from neurons in a Petri dish.

PHOTO: CORTICAL LABS

The technology is in its early stages of development, but it has caught the attention of the White House, which in March urged more research and development into the field to tap the potential of biological computing.

The company is also working with bioethicists to ensure that it does not create a conscious brain by mistake, or one that can feel pain.

“The last thing we want to do is create a system that can create pain and suffering,” said Dr Hon. “We, as an industry, will have to come up with ethical standards and guidelines if we are going to go down this path.”