Want to run a world-record time? Follow the green lights

Sign up now: Get the biggest sports news in your inbox

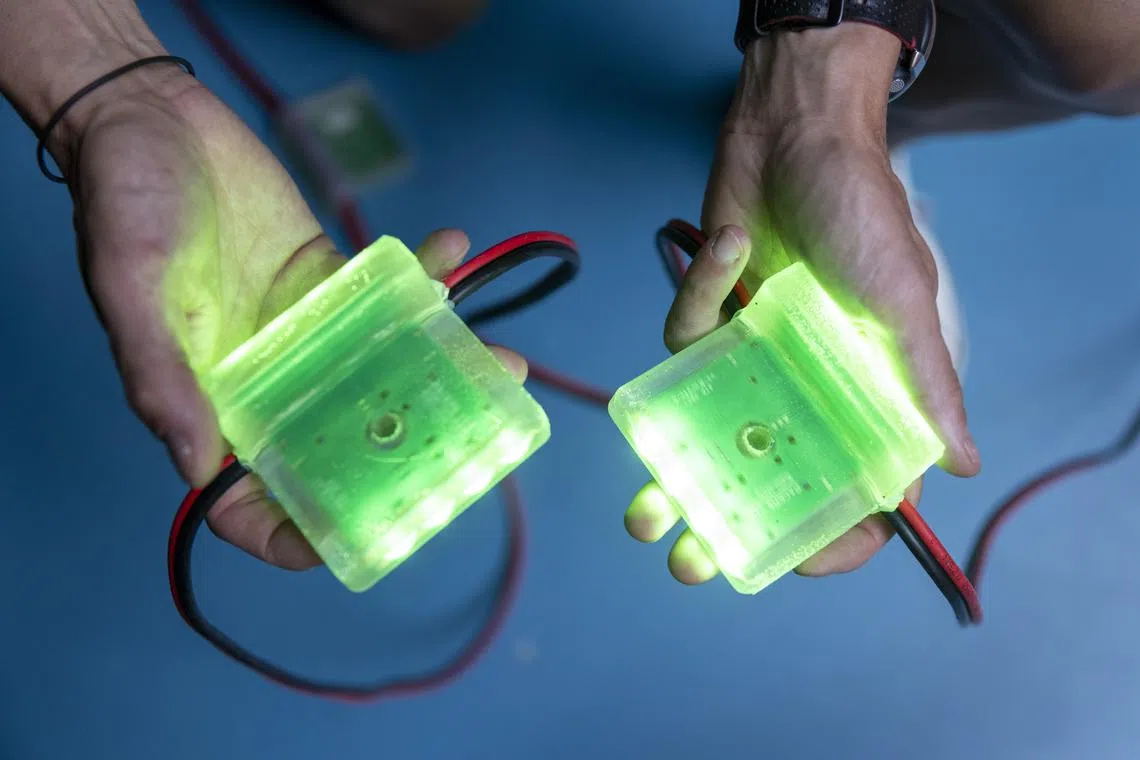

Wavelights have helped runners stay on a pace to break multiple world records.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

NEW YORK – Jakob Ingebrigtsen was ready to become a Pac-Man when he stepped on the track early in June.

Like the video game character that gobbles dots inside a maze, the Norwegian middle-distance runner was focused on keeping up with the bright-green flashes plotting his way along the inside of the track.

The flashes, called Wavelights, were travelling at the exact pace of the two-mile best time.

So, when he sprinted down the home straight on that summer evening at the Paris Diamond League meet, leaving the blinking lights in his wake, spectators knew they were witnessing the best performance in the world in the event.

Ingebrigtsen finished in 7min 54.10sec,

Pacemakers, who are runners tasked with setting a certain tempo in the early stages of a race, are nothing new.

Roger Bannister was helped by two pacemakers when he became the first runner to clock a sub-four minute mile in 1954, and few middle- or long-distance world records are set without the aid of a rabbit, as a pacemaker is known.

Bram Som, Wavelight’s co-creator and operational director, was a successful pacer after a career as a professional runner.

But while human pacemakers drop out at an agreed-upon point in the race, the green flashes do not tire.

The 400 LED lights installed at one-metre intervals along the inside rail of a standard running track accompany the runners all the way to the finish. Stay ahead of them, and the runner will have beaten whatever time to which the lights are programmed.

Too easy? For some, perhaps.

Like supershoes,

Som remembers the first rumbles of discontent after the device helped athletes break the women’s 5,000m and men’s 10,000m world records at the same competition in 2020.

“There was a lot of talk around it, with people saying: ‘Oh, it’s not legal. It’s technical doping. We don’t want that’,” he recalled. “But that was a breakthrough moment for us.

“The sport always evolves. We used to start running barefoot, then we got shoes, then they got spikes and now they have carbon plates. That’s sport. Now, we have a Wavelight and, in 50 years, there will be something different.”

There is an element of controversy around the blinking lights.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

But pacing was not the initial goal of the Wavelight technology. It was originally conceived as an interesting training aid to attract more people to athletics.

Som and Jos Hermens, who was Som’s manager throughout his track career, then turned a rudimentary product into the present-day Wavelight system.

The paradox of Som’s role in Wavelight’s creation is that the technology, on the surface at least, appears to threaten the existence of his former job.

After his running got him to the 2000 and 2004 Olympics, he switched to life as a pacemaker when injury denied him the chance to qualify for the London Games in 2012.

By the next year, he had developed a reputation as one of the world’s best rabbits, respected globally for his metronomic ability to run any requested pace. He was in demand for most major competitions, commanding a fee of US$2,000 to US$3,000 (S$2,705 to S$4,057) per competition.

He spent the next seven years earning more money as a pacemaker than he had at almost any other time during his competitive days.

The paradox of Bram Som’s role in Wavelight’s creation is that the technology, on the surface at least, appears to threaten the existence of his former job.

PHOTO: NYTIMES

Rabbits may no longer be needed in the future, but there was something more for Som as he watched Ingebrigtsen break the two-mile record.

The sense of satisfaction that once came from winning a race, and then from pacing a record run, now comes when the technology he helped create plays a part in sports history.

“The atmosphere in the stadium when an athlete passed the Wavelight or the Wavelight passed them was amazing,” he said. “It was like something I’ve never seen before.” NYTIMES