Sporting Life

In an unforgiving race, three young women offer us a priceless gift

Sign up now: Get the biggest sports news in your inbox

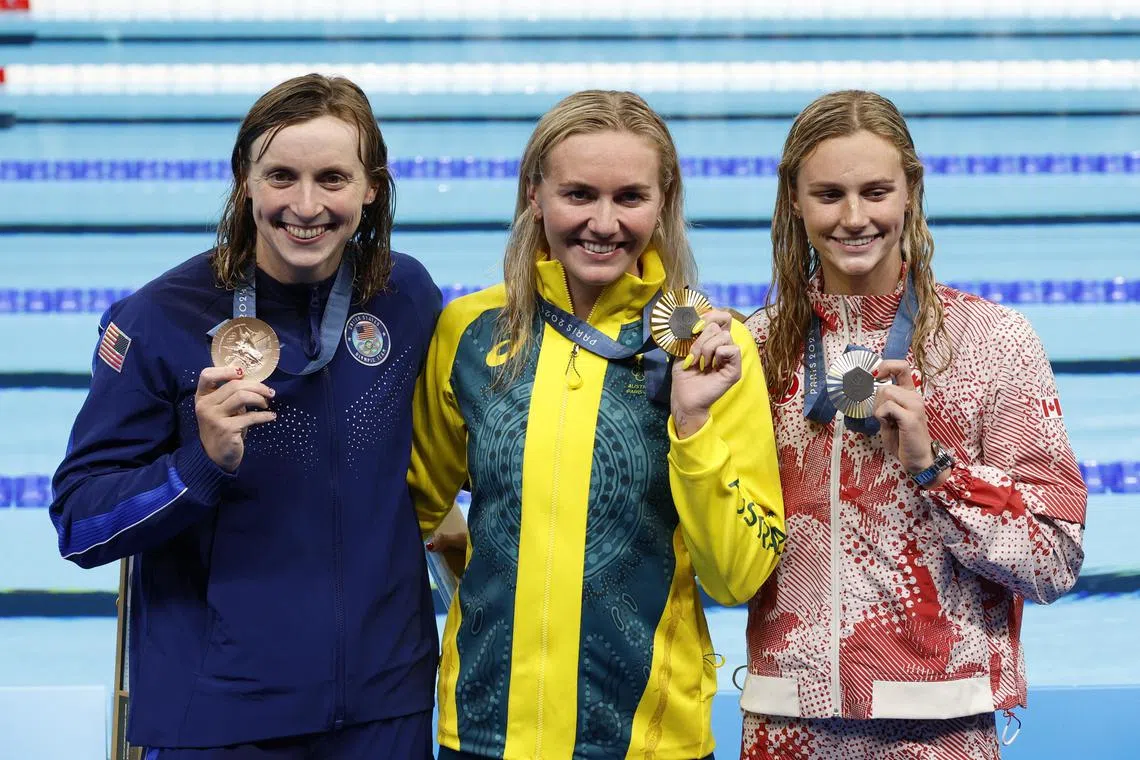

(From left) Bronze medallist Katie Ledecky of the United States, gold medalist Ariarne Titmus of Australia, and silver medalist Summer McIntosh of Canada after the 400m freestyle final.

PHOTO: EPA-EFE

PARIS – Every gold medal in Paris is set with a piece of the original iron from the Eiffel Tower. Every gold medal is 85mm in diameter and is 529g when put on a scale. Every gold medal looks exactly the same but sometimes it seems some have a different weight.

The gold medal has the same meaning to every winner but in how we perceive them they are not necessarily equal. Sometimes the sheer effrontery of an athlete gives a gold a unique heft. Like Usain Bolt at Beijing 2008, who could have stopped to tie his shoelace and won the 100m. Or the sheer insanity of a feat. Like Emil Zatopek in 1952, who won the 5,000m and 10,000m and then just for fun entered the marathon for the first time and won it.

And then sometimes, as on the night of July 27 in Paris, there is an irresistible glitter to winning the most talked-about, respect-laden, no-showing off, talent-heavy duel the Olympics have seen in a fair while. Like the gold medal comprehensively won by Ariarne Titmus on swimming’s opening night in the 400m freestyle. Katie Ledecky is a seven-gold Olympic legend, but over this distance she was 3.37 seconds slower than Titmus.

“Relieved” said Titmus (3:57.49) as she retained her title from Tokyo in 2021, holding off the teenaged Canadian Summer McIntosh (silver, 3:58.37) and Ledecky (bronze, 4:00.86) in the lung-busting eight laps and seven turns of the 400m freestyle. At the Paris La Defense Arena around 9pm was found a sound only sport knows: the point where excitement meets the extraordinary on a watery street of wonder.

Titmus, the Australian, came out for the race with a cheery wave and went to the wrong lane; Ledecky, the American, walked onto the deck as if wearing a mask of concentrated stone. She was met in France with a roar, for her legend has travelled across all waters. Then the buzzer sounded and it was the only time the Australian – reaction time 0.72 of a second – would be second all night to the American (0.68).

In a sporting world hijacked by exaggeration, this race deserved some hype. Long ago tennis star Jimmy Connors said of Bjorn Borg “I may follow him to the ends of the earth” and this was swimming’s version of it. This was athletes who go the extra practice length because of each other. As Titmus would say, “It’s fun racing the best in the world. It gets the best out of me. Hopefully it gets the best out of them.” Ledecky concurred. They understand that their feats are given meaning by who they race.

Between Ledecky, 27, Titmus, 23 and McIntosh, 17, were the 28 fastest times and six world records in the 400m. Eight lanes were filled with swimmers but respectfully Lanes 4, 5 and 6 were swimming their own private race. To paraphrase what the writer Jerry Izenberg wrote of Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, they were “fighting for the heavyweight championship of each other”.

Almost no one sees athletes train, the videos taken underwater to polish technique, the cords they drag to track power output, the paddles with sensors to see the direction of force they’re creating. Everything – says Singapore Aquatics swimming technical director Sonya Porter – is timed. The starts, the underwater, into the wall, off the wall, and every 10m.

“What’s their acceleration and deceleration,” she says. “How well are they holding it? Tempo is the turnover time of their arm stroke, so how fast are their arms turning over? What is the number of strokes they’re also taking?”

There is so much of themselves invested over years into roughly four minutes of swimming that fittingly Titmus’ first emotion was “relief”. It is, she explained, “a little bit more emotional, this one, than the first one. I know how hard it is racing in these circumstances, at an Olympic Games.”

A world championship, where athletes live in a hotel, mingle only with fellow swimmers, eat food possibly prepared by a chef, offers a finer environment for high performance. The Olympic Village is different and testing. “The noise, atmosphere, pressure,” said Titmus, “village life definitely makes performing well hard.”

It is a reminder that for all the diet, dawn alarms and endless kilometres, small things affect a race of small margins. A good sleep matters. Deafness to social media counts. And so does a calm, confident mindset.

“(In Rio 2016) after the 100m butterfly semi-final,” remembers Porter, “Joseph (Schooling) was on track. There was no way if he was in a great mindset that he was going to lose that race. Because everything was aligning.

“He was so calm, but there was still these moments where he came to ask certain questions and needed reassurance. Like did we really think he could do it? And so we sat down. Ryan (Hodierne, the biomechanist) had gone and broken down all the statistics to show him, and he just needed to see, ‘Hey I’m on track here’.”

In Paris, Titmus was on track from Lap 1. She led to the first wall and held it till the last wall. She could have gone faster and so could have Ledecky. “I didn’t have it in the last 250m,” said the plain-talking American. “I couldn’t kick into the next gear.”

Still, it was tense, a sense that something late might happen, even if it didn’t. Then the swimmers hugged and respect flowed. Ledecky praised young McIntosh for her poise and saluted Titmus as a friend. Titmus replied by saying, “I’m so honoured to be part of the race and to be alongside legends like Katie”.

Maybe then it’s not the gold only which was memorable. Maybe it’s the truth of how three remarkable athletes turned a race into the talking point of the aquatic Games. Maybe it’s the statement three young women made in how they raced one another.

That you can be of different ages, from different nations, but play sport unforgivingly but not boastfully. That you can be spent but not whine. That you can finish a hard day with grace. That in the end this is truly the priceless stuff of sport.