The Big Question

Can Carlos Alcaraz-Jannik Sinner carry men’s tennis on their own?

In this series, The Straits Times takes a deep dive into the hottest sports topic or debate of the hour. From Lamine Yamal’s status as the next big thing to pickleball’s growth, we’ll ask The Big Question to set you thinking, and talking.

Sign up now: Get the biggest sports news in your inbox

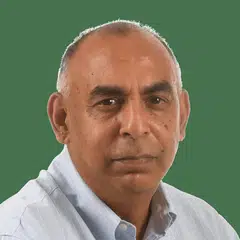

Jannik Sinner (left) of Italy and Carlos Alcaraz of Spain played in three Grand Slam finals in 2025 and also the ATP Finals in November.

PHOTO: EPA

A cracked whip, as Indiana Jones showed us, has a startling sound. It comes when the whip travels faster than the speed of sound and creates a miniature sonic boom. One might say a similarly intimidating sound emerges when Jannik Sinner lashes a forehand. The real whip leaves physical scars, the Italian creates mental ones.

Sinner, the ATP Tour Finals champion, strikes the ball with consistent violence. Carlos Alcaraz, the world No. 1, more a creature of inspiration than formula, whimsy not pattern, moves like a darting bee. When they play the air almost has the acrid odour of gunpowder. One talent is igniting the other.

A rivalry that got serious only two years ago is already rewriting numbers. Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal never played more than two Grand Slam finals against each other in a single calendar year. Neither did Nadal and Novak Djokovic, nor Djokovic and Federer. Sinner-Alcaraz have already done it three times this year

In 40 matches, across 16 years, only once, in 2006, did Federer-Nadal meet six times in a single year. In 2025, despite a three-month ban for Sinner, he and Alcaraz have equalled that number. Sinner has won six titles in 2025 and lost four finals, all to Alcaraz. The Spaniard has collected eight titles this year and lost three finals, two to Sinner.

Somdev Devvarman, who played both Federer and Nadal on the ATP Tour, says: “We’ve not even seen the best of them yet. That’s the scary part.”

The problem is tennis doesn’t just relish Alcaraz v Sinner, it depends on them. They’re the only salesmen who sell tickets, the only ones alarms are set for, the only pillars currently holding up a historic building.

Is that an issue?

“Yes,” says Mahesh Bhupathi, who won 12 doubles and mixed doubles Grand Slam titles between 1997 and 2012. “Everyone’s always just waiting for the final.” In Turin, during the ATP Tour Finals, the eight finest practitioners of the tennis arts gathered for a year-end shoot-out but Bhupathi only tuned in to the final.

“Unfortunately,” he says, “it’s the weakest (men’s) top 10 I’ve seen.”

Is depth an issue?

Even heroes need help, which is why Tom Cruise has a supporting cast in Mission Impossible. Back when the Federer-Nadal axis was in power, and later when Djokovic launched his own coup d’etat, they collected Slams as casually as a kid collecting Labubus, yet the field was thick with men trying to take their scalp.

Stan Wawrinka brought his muscle, Andy Murray his scowl, Juan Martin del Potro his Sidewinder of a forehand, David Ferrer his skates, Jo-Wilfried Tsonga his grin. This wasn’t just breadth of talent, but width of personality.

We like streaks and crave domination, but we also like statues shaken off their pedestals now and then. Nadal tripped against Ferrer (2011) and Fernando Verdasco (2016) at the Australian Open; Federer floated regally across the All England Club’s turf yet was mown down there by Tomas Berdych (2010) and Milos Raonic (2016). Always in the air there was expectation and edge.

In the current top 10, five men have reached a Grand Slam final. In mid-November 2010, it was seven of the top 10, in 2005 it was eight, in 2015 it was nine. If you didn’t bring your A-game those days, you could be shaken up. “Who will pull people now to smaller tournaments?” asks Bhupathi. And so we have to ask ourselves a question very respectfully: Would we buy a ticket for Wawrinka in the old days, or for Lorenzo Musetti now?

No one’s dissing the current top 10, for no one gets that far without a rare fusion of labour, art, austere lifestyles, desire. They are doing the best they can. Yet Shaheed Alam, Singaporean Davis Cupper, points to a recent stat, where the point difference between Sinner, No. 2 and Alexander Zverev, No. 3, is 6,340 points, while the gap between Zverev and the world No. 1000 is 5,145 points.

Those old guys, they spoiled us, says Shaheed and he’s right. The Big Three never ran dry of excellence as they defied one another and age. “We can hope,” he says, “Sinner and Alcaraz can maintain their level for the next 15 years, but there’s never any guarantee. That’s why you need a pool of five-six good guys to carry the sport.”

Let’s not overreact

Sport functions on suspense, its oxygen is its capricious nature, its tension arrives from the unforeseen upset. It’s not just a final we come to see, but a tight field scrapping and snarling to get ahead. Depth brings a collision of styles – like badminton’s wondrous generation of Tai Tzu-ying, Carolina Marin, Nozomi Okuhara, P.V. Sindhu, Ratchanok Intanon, Akane Yamaguchi, Chen Yufei, Saina Nehwal – and competitors push one another to rise higher. Then the game gleams.

But sport also runs in an endless cycle of ascents and slumps, some eras which glow and others in which tours rebuild. “When Roger arrived,” says Devvarman, “the world was blown away. How do we beat this guy? Then Rafa came and he showed us how you play a genius in his own genius way. Then Novak came and again we asked, how do you beat this guy?

“I didn’t know if tennis could be taken to another level. Then you see Sinner and Alcaraz emerging. Now again we’re asking, how do you beat these guys? The question has been passed on.” A question as old as the game itself and which mostly gets answered.

“It’s just a transition time,” says an unworried Devvarman. He and Shaheed both mention Joao Fonseca, only 19, a lethal Brazilian weapon in the making. Jakub Mensik, 20 and nicknamed Menimal, is another. Like volcanos, talent erupts without warning. Djokovic, we forget, was once a player of physical frailty, who suddenly found invincibility.

The game changed this century, says Devvarman, the balls lighter, the courts slower, kick serves died and so did volleyers, and to move the ball ferociously demanded firepower. It’s precisely the armoury Sinner and Alcaraz have. But Federer pointed out the courts require acceleration and if it happens the gap might close. Change is always hovering in the air.

Little things make a tour. Marketing, says Devvarman, for perhaps the ATP Tour needs to better sell the rest of the top 10 to us. Luck, always helps. “Someone,” says Bhupathi, “needs to beat both these top guys in one year” just to confirm there are contenders out there. It seems improbable right now, but strange things happen in sport: One mad summer even Nadal fell to Robin Soderling on Parisian clay.

Till then men’s tennis will remain in friendly hands. At the ATP Tour Finals, during a break in play, Sinner and Alcaraz chatted amiably at the net. Then the match resumed and they began denting each other’s armour. Some like this, athletes who play hard between the lines but don’t cross them once play is over. Others feel it’s all too cosy and sweet and that rivalries need a coating of testiness.

“(Pete) Sampras and (Andre) Agassi did not like each other,” says Bhupathi, “and you knew there was a resentment there. With Novak and Roger there was no love lost.” Bhupathi, and he’s not alone, enjoys a little friction, for it’s the burn of a grudge that often lifts athletes. And yet when the time comes, he, who knows talent, who’s seen it up close, will set his alarm just like us.

Sinner versus Alcaraz anywhere, any time, any surface, any field, we’ll wake up for.