At the Olympics, the music of sport requires 4,000 microphones

Sign up now: Get the biggest sports news in your inbox

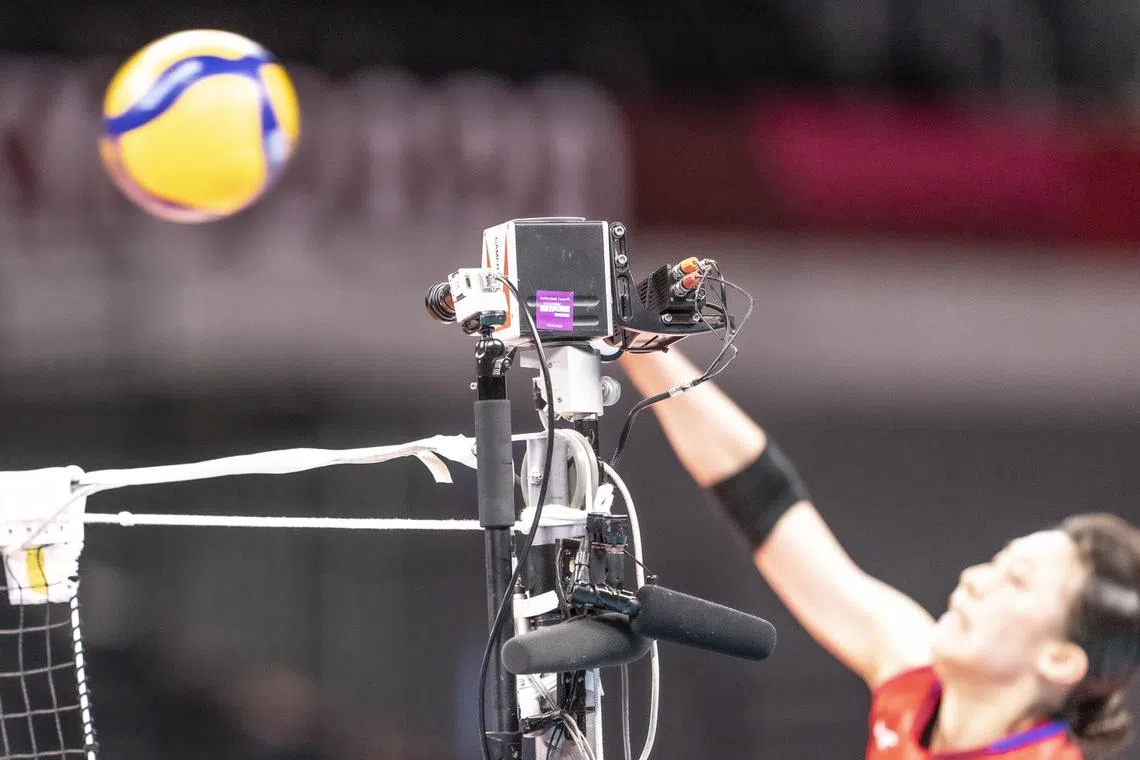

A microphone attached to the net will pick up the audible drama at the volleyball competition.

PHOTO: OLYMPIC BROADCASTING SERVICES

PARIS – The sporting sound engineer is an audio detective. Transmitting the music of sport – how do you convey the padding feet of a 42km marathon? – can be a mystery and he must solve it. So he studies acoustics in stadiums, collects auditory evidence and investigates where to put microphones.

Like under the ice.

Nuno Duarte, senior audio manager of the Olympic Broadcast Services, tells The Straits Times a lovely story. At the Winter Olympics, he says, “we had feedback that I was not expecting”. With all the music in figure skating, they worked hard to find a way to let watchers listen to the sound of the skates.

But athletes and coaches said, er, we don’t like it.

Why?

“They say,” Duarte explained, “when athletes do a lot of sound on the skates it is because he’s not performing well.”

Once – and just put your remote on mute for 30 seconds and try it – sport had no sound. In old, grainy black and white clips, humans run in silence and the crowd is wordless. The crunch of spikes cannot be detected nor the ragged breath of complaining lungs. Tapes are breasted but no cheer is ever heard. It feels like an incomplete story. Ballet absent of music.

It is why among the 10,500 athletes in Paris, not to mention thousands of coaches, physios, doctors, referees, umpires, linespeople, judges, journalists, volunteers are 300 unknown and vital people.

The sound engineers. The mike operators. The audio assistants.

A century ago exactly in Paris the Olympics had its first dance with sound as a scratchy radio broadcast began. Then sport felt distant, now every sigh is transmitted. If you hear the weightlifter kissing his bar and then grunting like a furniture mover, then thank the sound folks.

There isn’t a place at the summer and winter Games where there isn’t a microphone – 4,000 of them in Paris, using 35 different models – to bring you an audible story. You’ll find them on a volleyball net. Beside the archer as she fires. Even under the water in the swimming so you can hear the rush of a turn.

If forests have their own sound – chittering, roaring, humming, trumpeting – then sport has its own audible vocabulary. The tick-tocking table tennis ball, the splat of glove on flesh, the thump of a landing gymnast.

Sound is revealing sport and explaining it. The squeak of sneakers can suggest an athlete is braking. The vibration of a flexing diving board signifies lift-off. Always the ears give you clues. A mistimed shot has a particular sound in tennis and so does an ugly entry in diving.

Cabling for the entire Games starts around May and there must be miles of it. Just at the athletics stadium, where runners lope even as jumpers fly, there are, says Duarte, “seven (independent) productions”. In total, he says, “we have 73 audio consoles running at the same time on the first day of the Olympics”.

The sophistication of equipment has enhanced the experience. The watcher in the stadium can feel the electricity of the atmosphere, but the spectator at home sometimes has the advantage of clearer sound. Because microphones are attached to referees, but also –without interrupting them – to athletes.

The watcher in the stadium can feel the electricity of the atmosphere, but the spectator at home sometimes has the advantage of clearer sound.

PHOTO: EPA-EFE

“We put them on the sailors,” says Duarte. “So we can listen to the discussion between them. It’s been very, very successful and interesting.” In the stadium, you only see the high diver on the platform. At home, you might hear him. The steps he takes. His breathing if it’s fast. These tiny details, he says, “reinforce the content”.

Sound is entertainment yet insight. Even commentators, who are part of the sound, are tuned to the nuances of vibrations. From the Winter Olympics, Duarte offers another example.

“If the commentator is a former athlete (then from) the sound of the skis on the snow, he understands if the snow is soft or hard. And immediately he can understand if the athlete that is on the course is going to be a better performer than the past one. Because he understands if the snow is hard, he’s going to be fast.”

The music of sport is reassuring and yet it is not always recognisable. As equipment alters so does the sound they make. New sports emerge and the soundtrack alters. There’s the unfamiliar scratch, scrape, squeak of the skateboarder and padding, rushed feet of the vertical sprinters on the rock wall. And, now and then, the “in da hole” shouting golf fans who desperately need a mute button.

And yet, as always in sport, there’s a lacing of irony to all this. Even as we crave sound, and even as athletes arrive at the field with music streaming out of their headphones, once they’re ready, they go deaf. To be in the zone, that holy place, is after all a place of concentrated quiet.