News analysis

East-West Line probe shows no detail is too minute in rail maintenance

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

SMRT personnel inspecting the carriages of the affected train outside Ulu Pandan Depot at around 1.45pm on Sept 25, 2024.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Follow topic:

SINGAPORE –The outcome of a months-long investigation into one of Singapore’s worst MRT breakdowns is a stark and vital reminder that no single part of the rail system – even something as basic as grease – can be ignored.

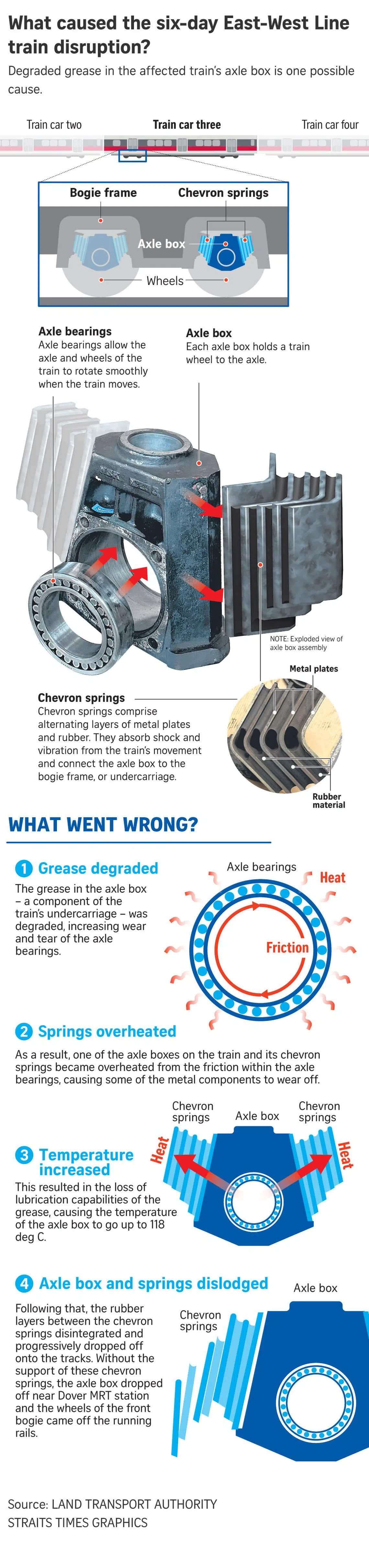

Degraded grease on a faulty part of a train’s undercarriage was pinpointed as the likely cause

Several points raised by investigators in reports released on June 3 highlight the need for rail operator SMRT to tighten its procedures and take early signs of a fault seriously. They also point to the importance of greater regulatory oversight of maintenance procedures.

First, while it was commendable of SMRT to install a tool on its own initiative to detect overheating in an undercarriage component called an axle box, the system did not work as intended.

On Sept 25, 2024, the tool detected a temperature of 118 deg C on the faulty axle box – an early sign of overheating – but the system could not identify which train it was on.

As a result, a staff member believed the notification to be a false warning and did not follow up.

This was a missed opportunity for SMRT to nip the problem in the bud, given that the temperature reading came almost two hours before the axle box dislodged from the train. An axle box holds the train’s wheels to the axle, a rod connecting a pair of wheels.

Had the tool worked and the operator’s protocol been activated, the train would have been withdrawn immediately

The findings from an independent Transport Safety Investigation Bureau (TSIB) probe were also instructive.

It found that SMRT staff had told their supervisors about the system’s inability to identify trains with axle boxes of higher temperatures, but the issue went unresolved.

Nor were staff trained on what to do if they encountered this issue with the system.

TSIB noted that consequently, SMRT staff had been treating these readings as false warnings and could have been desensitised, “resulting in diminished response to warnings and alerts over time”.

The faulty train could have been withdrawn to a depot sooner, if staff had been told not to regard the alerts as false warnings, the bureau concluded.

TSIB investigates rail incidents involving derailments, collisions, runaway vehicles, fires or explosions, as well as those that result in serious injury or death. No one was hurt in this incident.

Its 28-page report – only its third for a rail incident – set out a thorough sequence of events on the day of the incident and a technical analysis of what could have gone wrong.

In the September 2024 incident, a section of the train’s third carriage derailed after the axle box fell out. As a result, the train caused extensive damage to 2.55km of tracks and trackside equipment as it was being withdrawn to Ulu Pandan Depot.

While SMRT has fixed the issue and the temperature monitoring system can now identify affected trains, its earlier inaction is a timely reminder that early warning signs should not be disregarded.

In this case, fixing the problem as soon as it cropped up, and acting on staff feedback, could have made the difference.

It is encouraging to note that Singapore’s rail regulator, the Land Transport Authority (LTA), and SMRT are planning to install more trackside infrared sensors to improve this temperature monitoring tool.

More regulatory scrutiny in other areas vital to the safety and reliability of MRT rides is also overdue.

Workers replacing the damaged track near Dover station in September 2024.

PHOTO: LTA/FACEBOOK

LTA’s eight-page investigation report revealed that SMRT had extended the interval between overhauls for the faulty train – a first-generation workhorse from Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI) – without a detailed engineering and risk assessment.

At the time of the incident, the train had logged 690,000km since its last overhaul in 2018, after SMRT lengthened the interval between overhauls from 500,000km to 750,000km.

TSIB separately noted that the quality of the undercarriage equipment that failed on the affected train was no longer assured beyond 500,000km.

On its part, SMRT pointed to supply chain disruptions arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, which delayed the delivery of new trains meant to replace the first-generation models, as well as spare parts needed for overhauls.

While LTA was aware that SMRT had a system to vary its overhaul intervals, there was no requirement for the operator to notify the regulator when these were done.

SMRT also could not provide records of some of its assessments for extending the affected train’s overhaul interval.

This prompted the TSIB to state that the importance of record-keeping and documentation “cannot be over-emphasised”.

The fact that LTA will now play a bigger role in overhaul decisions should be welcomed.

Operators will now have to flag to the authority changes to overhaul intervals for systems that are critical to safety. LTA will also review the completeness of operators’ engineering assessments.

Given the highly complex nature of the MRT system – where any of the thousands of parts can fail suddenly – having LTA as an extra layer of checks will help close any gaps that operators may inadvertently miss.

It also bears noting that SMRT’s maintenance practices have differed from those recommended by the train manufacturer KHI.

For example, SMRT carries out a grease leakage check once every three weeks, while KHI recommends such checks to be done weekly.

SMRT said this maintenance regime has been in place since the trains began operating in 1987. It did not have records explaining the merits of these maintenance intervals, noted TSIB.

The length of time for which a maintenance regime has been in place does not, on its own, justify its continued effectiveness.

The KHI trains have aged significantly over their more than three decades in operation. The question is, would relooking the maintenance regime and adapting the frequency of checks to maintenance needs have made a difference?

For the six-day disruption between Jurong East and Buona Vista stations, SMRT will be fined $3 million

The record was a $5.4 million fine imposed on SMRT for a 2015 disruption where the entire North-South and East-West lines went down for more than two hours during the evening peak. Some 413,000 passengers had their commutes disrupted.

LTA had explained that a lower fine was imposed this time because a shorter stretch was affected, even though the disruption lasted six days.

The authority’s assessment was that SMRT had recovered the system in the shortest possible time without compromising safety, and hence, it did not penalise the operator for prolonging the disruption unnecessarily.

SMRT and the hundreds of workers who chipped in deserve plaudits for going all out to restore services quickly and safely after the incident.

LTA also noted that before the incident, trains on the East-West Line clocked more than 2 million train-km before encountering delays of more than five minutes.

This is a marked improvement over the 133,000 train-km that the whole MRT network managed a decade ago, when rail disruptions occurred more frequently. It is also more than double the 1 million train-km target that the Government has set.

Yet, any rail disruption – notwithstanding the number of stations affected – will have a considerable impact on passengers.

The protracted six-day disruption in September 2024 left many passengers anxious and confused, and late for work or appointments.

Faced with snaking queues for free buses between affected stations and a much longer journey overall, some commuters resorted to taking private-hire cars at prices many times higher than the norm.

The takeaway from the incident is that SMRT has to exercise constant vigilance over its trains and their many components – particularly as they age – and heed even the smallest warning signs at all times.

When it comes to rail maintenance, no detail is too minute.

Kenneth Cheng is assistant news editor at The Straits Times. He oversees transport coverage, spanning the land transport, aviation and maritime sectors.