Lunch With Sumiko

Lunch With Sumiko: The world is conductor Wong Kah Chun's stage

Wong Kah Chun flies the Singapore flag conducting orchestras around the world

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

When Wong Kah Chun was in Primary 1 at Jurong Primary School, his form teacher, who was also in charge of the brass band, passed every pupil in the class a consent form.

"He said, 'Take home and let your parents sign,'" remembers Wong. His parents duly did, and that was how he ended up learning to play the cornet in the band.

Fast forward two decades, and the world is now his stage.

Wong, 30, is one of the most exciting things to happen on Singapore's Western classical music scene.

In May last year, he won the prestigious international Gustav Mahler Conducting Competition held in Bamberg, Germany. The contest, named after the Austrian composer, is open to conductors no older than 35 years and has launched careers.

The win has opened many doors for him and he is booked until 2020.

Earlier this year, it was announced that he will be chief conductor of Germany's Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra, the first Asian in this role. He starts a four-year stint in September next year.

It's been a wild ride so far for someone who, as he puts it himself, comes from a modest, Mandarin-speaking background and had no one-to-one music lessons till he was in his late teens.

We meet twice - once when he's back in January for the Chinese New Year, and again in late March, when he's in town for a short visit.

Our first meal is at National Kitchen by Violet Oon at the National Gallery. The second is drinks in Bukit Merah at Seng Hong coffee shop, now known as Hollywood Bistro.

Wong is warm and friendly in person but there is also a gravity and thoughtfulness to his manner that belie how he is just 30. He speaks eloquently and his eyes light up when he talks about his music and an arts project with children that he's doing.

His life is a whirlwind of conducting jobs in different cities. Between our first and second meetings, he was in Berlin, Dresden, London, Nuremberg, Budapest, Vienna, Rotterdam, Shanghai and Tokyo. After that he's off to Los Angeles, Kunming, Tokyo, Munich, Yokohama, Luxembourg and Paris - and that's only up till July.

He clearly misses his kopi-c-peng (iced coffee with evaporated milk) because he orders it both times we meet. "Taste of home," he grins.

He used to be based in Kanagawa in Japan, surrounded by beaches and mountains and, on a good day, Mount Fuji in the distance. "It's my oasis where I'm disconnected from the world," says Wong, who has a Japanese musician girlfriend. But with more conducting jobs after the Mahler win, life has become more nomadic.

He's not complaining, but he does miss home. "It can be good hotels but somehow my home in Jurong is the best - no air-con, second floor, gets stuffy, gets sweaty at night, but it is home, better than a hotel."

HE GREW up in a five-room flat in Jurong West Street 42.

His father, Victor Wong, 67, is a warrant officer in the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) who will be retiring soon, and his mother, Yeo Huay Lan, 62, a childcare teacher. He has two younger brothers - one working in engineering and the other in tourism.

Western classical music wasn't a part of family life where more Mandarin than English was spoken. The closest to that world was an old piano which his parents found discarded in a void deck and brought home. His mother played it occasionally.

His path to being a conductor was a lucky confluence of events.

He got into music when he and his classmates were practically forced to join the primary school brass band. Some dropped out along the way, but he kept at it because band practice was fun and "a social event".

"I had this privilege of beginning my music as a group, so it's always like a team," he says.

At River Valley High, he joined a concert band and played the trumpet. At Raffles Junior College, he joined the symphonic band and took music as an A-level subject.

A twist of fate led him to join the Singapore National Youth Orchestra (SNYO) after he stood in for a JC friend who couldn't make some rehearsals.

SNYO was the first time he had contact with a Western symphony orchestra with strings. He also got free one-to-one lessons with musicians from the Singapore Symphony Orchestra (SSO), and realised he could have a career in a professional orchestra.

"I started late," he says. "I'm not like a three-year-old prodigy who started on the piano before I could speak, and went for my first competition at 10 years old and won something. It wasn't like that."

What we ate

National Kitchen By Violet Oon

National Gallery Singapore, 1 St Andrew's Road

2 San Pellegrino: $14

1 Kopi VO c-peng: $5.50

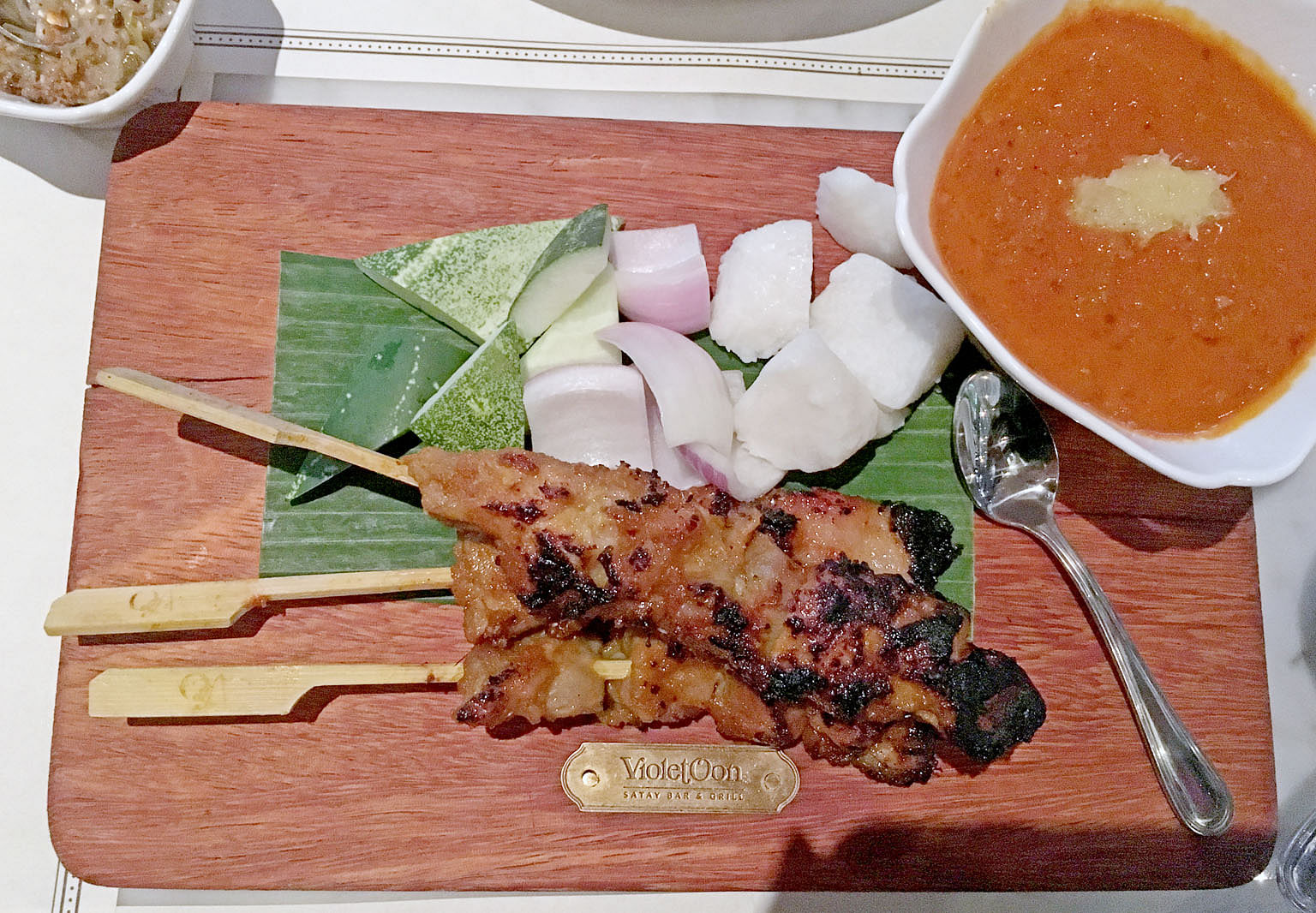

1 Satay: $14

1 Hainanese chicken rice: $17

1 Buah keluak ayam: $23

1 Sayur lodeh: $13

1 Jasmine rice: $1

2 San Pellegrino: $14

1 Kopi VO c-peng: $5.50

1 Satay: $14

1 Hainanese chicken rice: $17

1 Buah keluak ayam: $23

1 Sayur lodeh: $13

1 Jasmine rice: $1

TOTAL (with tax): $103

Watch video online

Which city has the best food? Wong Kah Chun on beef in Argentina. http://str.sg/4BWD

Which city has the best food? Wong Kah Chun on beef in Argentina. http://str.sg/4BWD

He was in the SAF military band during his national service. But he suffered a nerve injury to his lips from over-playing the trumpet. Because he couldn't play for a few months, he started composing.

"Of course no one would want to conduct this young boy's music, so I had to form my own team of musicians and I had to conduct myself, which was how I got into conducting. It was all very natural," he says of his foray into conducting in front of his NS mates.

His A-level results were good enough for him to be offered a place to do physics in Cambridge, but he instead got a scholarship to the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music at the National University of Singapore and read composition.

He had nurturing lecturers there, including the dean, Professor Bernard Lanskey, who got him to learn other instruments like the piano and stringed instruments which make up an orchestra. He chose the viola.

After graduation, he worked as a conducting assistant with the Singapore Chinese Orchestra under the mentorship of music director Yeh Tsung. This stint gave him a good grasp of both Western and Chinese music.

In 2010, he and a few young musicians formed the Asian Contemporary Ensemble to champion Singaporean and Asian composers.

He later got another scholarship, to Berlin's Hanns-Eisler Musikhochschule for his master's in orchestra conducting and opera conducting. His mentors have included the late German maestro Kurt Masur and Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen.

Along the way, he picked up a first prize at the International Conducting Competition Jeunesses Musicales Bucharest.

But there were failures too. "I've applied for so many competitions and got rejected and rejected," he says. "But I think my attitude is, you've got a hundred failures and you just don't think about them."

BEFORE he won the Mahler competition, he had already led orchestras in more than 20 cities in four continents. Winning has meant a lot more recognition as well as the luxury of being more selective about jobs.

He notes how young conductors are often eager to take on jobs even if asked to perform composers they are not familiar with.

"The danger is that if this is not a piece that I'm completely immersed in, I run a high risk of not being able to deliver, to show the best I can to the orchestra, which means that in the future I might not be re-invited by the orchestra," he says. "But if we have enough confidence and we say, let's take it one year later or two years later, it could be even better."

He is represented by Columbia Artists Management and has a manager who helps him with his schedule.

He does a lot of homework before each performance. "This is very Singaporean, right, we just want to be kiasu."

For example, he has a stint in France in November. He is already planning how, because he will be in Italy in September, he will make a detour to France and attend a concert by the orchestra incognito.

"I will buy my own ticket. I don't want them to give me a ticket and then, in exchange for that €30 (S$45) they know I'm there," he says. "I want to be very ninja and just see how they react to their conductor, how they react in performance." That knowledge will help him understand the musicians better.

I observe that a conductor's life seems lonely and he agrees.

But "there are ways in which we can free ourselves from this solitude", he says. He likes to join musicians during breaks for coffee and biscuits. He doesn't hole himself up in his hotel room. "It's not my style yet. Maybe when I'm 50, maybe I will be a little bit strange, more strange," he laughs.

For now, he just wants to do normal things. In cities where he is put up in hotels near the concert venue, he prefers to walk back than be ferried around. "I have Google Maps."

Do conductors make a lot of money, I wonder. "If you're successful, it comes in," he says.

Things are more comfortable now, but money has always been tight because, whatever he earns, he has ploughed back to, say, going overseas to study with someone.

"If I earned $2,000, I spent $2,000," he says. "But in retrospect it has been always investing in myself... I always took it as an opportunity to grow, to learn, to practise."

Would he like to work with the SSO on a long-term basis? He says: "It would be my privilege to serve. Not just the orchestra but really to serve my community - I want to give back to the community that has raised me."

Giving back is something he talks a lot about at both our meetings.

Last year, he co-founded Project Infinitude with Ms Marina Mahler, the granddaughter of Gustav Mahler. It's part of a global music education initiative with the Mahler Foundation she founded.

The four-month pilot project exposes less privileged and special-needs children to music in a fun, group setting - just like how he himself discovered music.

He talks enthusiastically about how Project Infinitude has brought together 20 children in Singapore. His visit in March was because of a concert the children put up.

Looking back, he knows how lucky he has been and is especially grateful to his supportive parents.

"In the past, I used to complain more," he says. "When I was in JC or at university, I was always saying, you know, I'm so envious of someone who is able to learn the violin from two years old and, you know, from three years old you get to study with SSO musicians , and they have got the money, their parents also are musicians, so, you know, they have got the full package.

"But now, I feel that, in fact, it is a blessing because my parents, they never had any expectations for me. I'm the eldest but I don't behave like that. I'm supposed to be the one who gets a stable career, gets married and has children so that they can be grandparents, but they never had any expectations like that."

He adds: "I always had dreams. This is very much what I would have liked it to be. It has worked out so well that I am so content - which is dangerous because when one is content, then it can be very easy to just stay in one spot and say everything is enough."

It's unlikely, though, that this talented, hard-working and ambitious young man will stay in one spot. But, one suspects, he will remain grounded no matter how far he goes.

Twitter @STsumikotan