Commentary

The Megan Khung report was painful to read, but offers hard lessons to prevent another tragedy

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

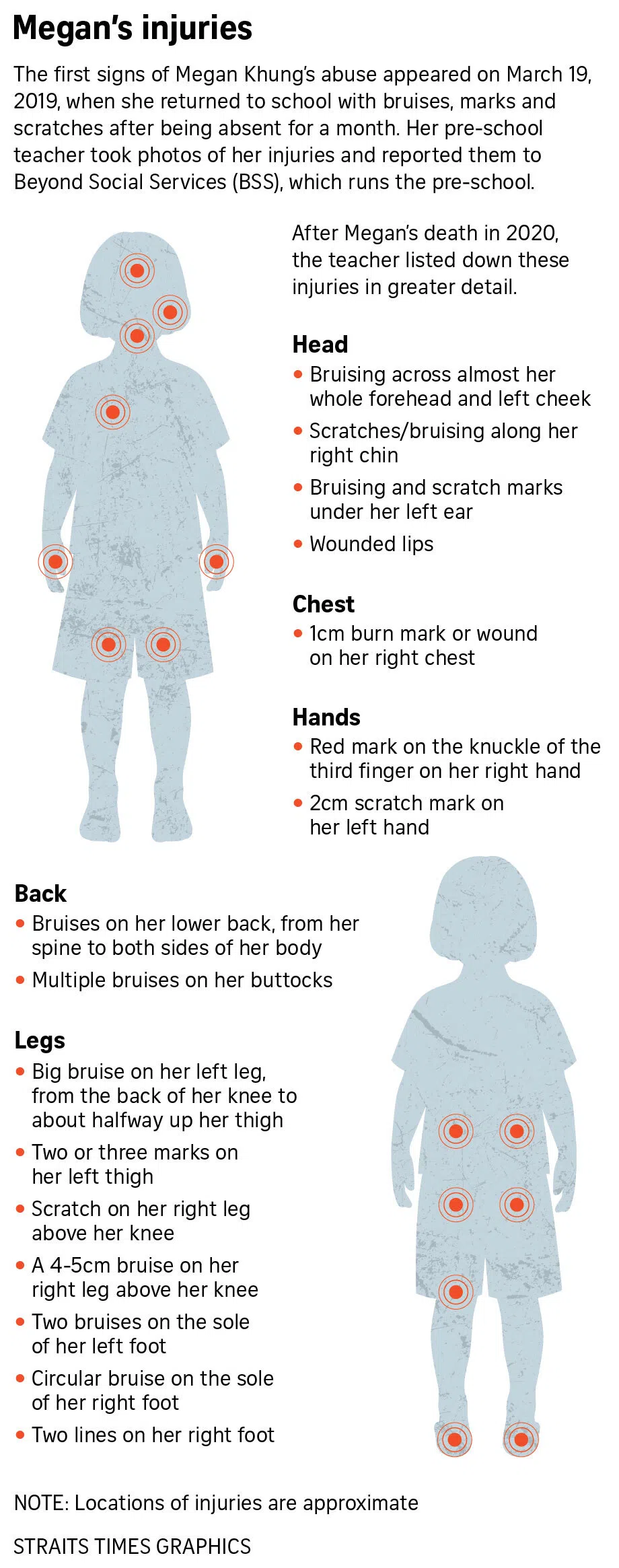

Four-year-old Megan Khung suffered more than a year of abuse at the hands of her mother and the woman's then boyfriend.

PHOTOS: CCXXCXCX/INSTAGRAM, SHIN MIN DAILY NEWS, INSTAGRAM

Follow topic:

- A review panel found failures in the system regarding Megan Khung's death, including missed chances to save her due to procedural breaches.

- But beyond the feelings of shock and anger, this case ought to spur an urgent resolve to find and fix the gaps in the child protection system.

- The review of Megan Khung’s case by an independent panel is Singapore’s first such instance in almost 30 years since the case of Winny Ho, a five-year-old girl was so badly abused by her mother that she nearly lost her sight and suffered brain damage.

AI generated

SINGAPORE – I found it painful to read what an independent review panel had found on Megan Khung, a four-year-old girl who died in February 2020

The account of her injuries inflicted by her mother and the woman’s then boyfriend set out in the report, and the series of missed opportunities to save her life, stirred both dismay and anger.

Take, for instance, two calls made by Beyond Social Services (BSS) in September 2019 to the Child Protective Service (CPS), which comes under the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF). BSS runs the pre-school that Megan attended and had raised concerns about her safety.

Yet the calls did not get the attention they deserved.

The CPS officer involved failed to probe further to better assess the case and even neglected to log the calls – a breach of procedure that meant supervisors never had a chance to step in.

Then in January 2020, a police officer assessed the case as low-risk after Megan’s grandmother made a police report. The officer tried to locate Megan’s mother for about two weeks and failed to do so, but did not inform her supervisor.

This failure to follow processes prevented timely and appropriate action when the police report was made, the panel said in its report released on Oct 23.

Two police officers have been disciplined, and one of them has since resigned. The MSF has also begun a disciplinary investigation into the CPS officer’s actions.

The panel found a lack of clear understanding and communication among the agencies involved – a breakdown in communication, coordination and action that proved tragic.

Hard lessons learnt

But beyond the feelings of shock and anger, this case ought to spur an urgent resolve to find and fix the gaps in the child protection system.

After the initial rush of emotion, it’s instructive to take a step back and consider what lessons can be drawn from what happened, and how Singapore can strengthen the safeguards for its most vulnerable children.

One recommendation from the panel is that child protection case management agencies should manage all child abuse cases, and be “adequately resourced” to do their jobs effectively.

These agencies include the CPS, which handles high-risk cases, and child protection specialist centres, for low- to moderate-risk cases.

This is key as the agencies that encounter and report abuse could be childcare centres or non-profit groups that run programmes for children. They cannot be expected to have the depth of experience and the competencies needed to manage child abuse cases adequately.

When roles are clearly defined and everyone knows which agency is in charge, cases are less likely to fall through the cracks – a risk that increases when multiple agencies are involved but no one takes ownership, or when the agency that ends up taking charge is not equipped to do so.

Child protection work is complex, and demanding in all senses of the word.

Child abuse cases can be arduous to manage when parents face myriad problems, do not see that what they are doing to their children is abusive, and lie and hide to cover their tracks.

It takes professionals with the right training, experience and competencies, and who are working in agencies with the necessary processes and systems to handle such cases where the stakes can be literally life or death.

Supporting those who protect vulnerable children

While the panel’s report did not address staffing levels, it’s a no-brainer that child protection agencies must have enough manpower and their workloads must be manageable.

Officers must also feel equipped and supported to do the difficult work of protecting vulnerable children.

According to MSF, the average caseload for CPS officers has fallen from about 40 cases an officer between 2018 and 2022 to about 35 cases an officer in 2025.

In addition, the ministry has brought in support staff to handle ancillary tasks, freeing protection officers to focus on their core work – such as investigating and managing cases.

The MSF has also stepped up its recruitment and retention efforts, offered structured supervision and mental wellness support, and rolled out technological solutions to reduce the administrative burden on protection officers.

Another significant recommendation is the setting up of an appeals mechanism to address differences in views regarding risk levels and how cases should be managed.

This would ensure that all reports receive appropriate attention and no concerns are dismissed too quickly, the panel said.

First independent review in almost 30 years

The review of Megan’s case by an independent panel is the first in Singapore in almost 30 years, since the case of Winny Ho. The five-year-old girl was so badly abused by her mother that she suffered brain damage and nearly lost her sight.

In 1996, a Committee of Inquiry was convened to examine how the authorities handled Winny’s case.

The committee found that there was no negligence in the way government officers handled the case, but there were errors of judgment as the welfare officers had little experience and formal training.

There was also insufficient coordination between the agencies investigating the case.

Both cases highlight the critical need for accountability and taking responsibility. Individuals should be taken to task when there are breaches or wrongdoing.

But we should also be mindful to avoid a culture of fear or blame by baying for blood whenever something goes wrong.

If child protection officers are vilified or unfairly blamed when something goes south, it will become harder to attract and retain the very people Singapore needs to keep children safe.

And the need is immense.

In 2023, the latest year with available data, there were 2,787 new child abuse cases assessed as low- to moderate-risk, and another 2,011 new cases classified as high-risk.

And these are just the new cases, not counting existing ones.

Protecting children from abuse requires all hands on deck – a system that is sufficiently resourced and better coordinated, with all parties working together to ensure no child falls through the cracks again, like Megan did.

That must be our collective assurance given to our most vulnerable who deserve nothing less to keep them safe.