The faces behind the aid figures

At least 91,000 people received a helping hand in the form of financial aid from the state in 2014. Insight looks at six families and individuals who typify those on social assistance in Singapore.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Janice Tai, Toh Yong Chuan

Follow topic:

Two months ago, the Government for the first time released detailed figures on the breakdown of citizens who received financial aid from the state.

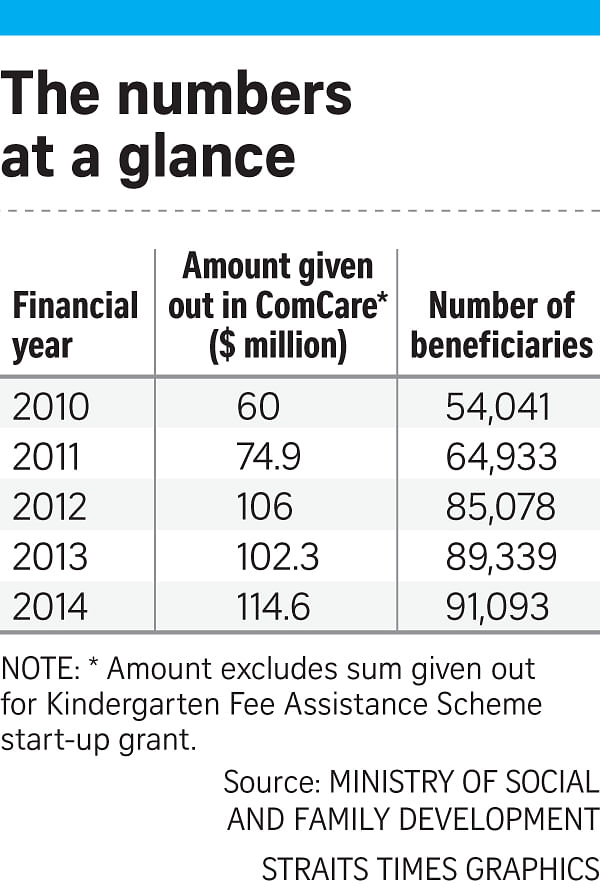

In the financial year ending March 2015, 91,093 Singaporeans - or about 2.7 per cent of the citizen population - received $116 million in some form of social assistance.

This was a sharp jump from the 54,041 who received $61 million in aid in 2010.

"The increase is not too surprising because we have increased our efforts in the last few years to bring help closer to those in need," Social and Family Development Minister Tan Chuan-Jin said last December.

The criteria to determine who can benefit from ComCare - the Community Care Endowment Fund - have been revised "so that more can be assisted", he explained.

ComCare was tweaked to benefit more families who require short- to medium-term assistance.

Among others, the household income cap was raised from $1,500 to $1,900, and the per capita income criterion was reviewed so that families with more dependants could qualify.

Some observers have described this as a government "shifting to the left". Yet it is worth noting that much of this aid is not just a handout, but also targeted at helping struggling families and individuals get back on their feet.

The Sunday Times looked at six cases of people receiving some form of social assistance from the state.

At the practical level, they all have a roof over their heads. Hearteningly, they look beyond that, too, expressing a desire for a better life for their children. And they show resilience and resourcefulness to not just rely on the financial assistance.

"I am upgrading (my skills) to provide more for the family," declared one of them, security guard Vengatalakshmi Velusamy, 34, a mother of two young children, who is training to be a healthcare assistant. She is the sole breadwinner as her husband is an Indian national who cannot currently work here.

When Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat announces the annual Budget next month and MPs debate government spending for the year ahead, some attention will turn to whether this pool of citizens continues to get adequate support.

Some perennial questions will likely also be asked. Among them: Who are these poor Singaporeans who are receiving financial help from the state? How did they land in dire straits, and how likely are they to be able to escape their plight?

Some answers came last year, when the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) released the demographic profile of those receiving ComCare help. ComCare provides three broad types of assistance: long-term help, largely for the elderly poor; interim and short- to medium-term help for those facing crises like illness or retrenchment; and kindergarten and student-care subsidies for children.

About half of the households receiving short- to medium-term help live in one- or two-room HDB flats. One in four households has the main breadwinner working; one in four households has the breadwinner looking for work.

The MSF did not elaborate on their racial backgrounds, or what led to their financial hardship.

But questions remain: Do these folk constitute what passes for "poverty" in affluent Singapore? Might there be others like them who need help but have not received it?

Singapore has no official national definition of poverty, unlike some countries such as the United States which have poverty thresholds based on household income and size.

Three years ago, then-Social and Family Development Minister Chan Chun Sing explained that the Government has "multiple lines of assistance across the entire spectrum rather than having one line".

The ministry's website points out that its help schemes typically cover the bottom 20th percentile of households, with the flexibility to go beyond if the family's circumstances merit consideration.

However, in the absence of an official definition of poverty, the 2.7 per cent of citizens receiving ComCare help could be seen as a proxy measure of the extent of poverty here.

As to what lands people in the poverty trap, a study by the Lien Centre for Social Innovation last year identified some root causes: Low-wage workers' wages are depressed due to the influx of cheap foreign labour, and workers are left out of economic growth.

Help for these affected workers has been stepped up. Those earning $1,900 or less a month receive Workfare income supplements in cash and top-ups to their Central Provident Fund accounts.

Some 372,245 workers received $422.8 million for working between January and September 2014, up from about 320,000 workers who received $343 million in 2009.

Thanks to these schemes, the incomes of the bottom fifth that stagnated between 2001 and 2010 have improved, growing by an average of 2.1 per cent a year from 2010 to 2015 after taking inflation into account.

Social workers note that there remains a group of core poor in Singapore - mostly the elderly and sick who cannot work. This group on long-term ComCare assistance has remained relatively stable - 4,134 in 2014, up from 3,479 in 2010.

Then there are those whose incomes have not caught up with rising costs. "Many people still live from hand to mouth because their income levels fail to catch up with the cost of living," says Mr Wee Lin, chairman of Sunlove Abode, which runs a network of seniors activity centres and clinics.

The number of those getting short- to medium-term ComCare help grew from 30,908 in 2010 to 67,926 in 2014.

Mr Seah Kian Peng, who chairs the Government Parliamentary Committee for Social and Family Development, said unemployment and medical or family issues could have driven more to seek help.

Some of these underlying causes and issues were found in the five families and one individual whom The Sunday Times spoke to.

Five of them are on ComCare and one family could have qualified for such aid, but did not seek help.

Their stories - the faces of the social transfers that have become a key part of today's Budgets - highlight the necessity of such financial help, as well as the role charities and others in society can play.

Stories of hardship, resilience and hope

It was conceived around the simple idea of letting those struggling with their finances tell their stories.

The reporters would craft their life stories to give The Sunday Times readers a broad, unvarnished ground-up picture of what living in financial hardship is like.

Teen hopes to break long cycle of struggle

Since birth, he has been raised by his 74-year-old grandmother, Madam Pon Md Nor, and his 85-year-old grandfather, Mr Ahmad Taman.

Until this month, Mr Ahmad was the main breadwinner, earning around $1,500 a month as a security guard. But he has just been diagnosed with lung cancer, after he had a fall at work and was taken to hospital.

Mum's burden with husband on visit pass

This is because her husband, a 34-year-old Indian national, is not able to work here. He and their son, also an Indian national, are on visitor passes which they need to renew every month. The Immigration and Checkpoints Authority (ICA) has also rejected Mr Betthi's application for a long-term visit pass, and also for a student pass for the couple's son, Balakrisha.

It falls on Ms Vengatalakshmi to provide for the family - which has also expanded, as the couple had a daughter, Lineysha, born in Singapore in 2014. The 34-year-old mum works as a relief security guard for about $70 a day, earning about $1,600 a month.

Family of 7 live on $1,300 a month

But Mr Ong, 49, is literally sandwiched between his wife and three daughters on two beds joined together in a room every night. His family of five would squeeze in a room because the other room in their three-room flat is occupied by his parents.

Though he promised his wife when they got married 13 years ago that they would get a place of their own, it has yet to materialise because finances are tight.

From own 5-room flat to 2-room rental

The 52-year-old owned a van and ran a one-man courier company, and wife Geraldine Chen had a small gift-and-flower stall in Clementi. They lived in a five-room Housing Board flat in Pasir Ris with their three children. They could even afford a maid.

Today, the couple and six of their now seven children live in a two-room HDB rental flat in Clementi about the size of four parking spaces. Mr Leck is unable to work because of a heart problem and high blood pressure, and his wife stays home to look after the children. Their only income is $1,200 a month from ComCare.

'No money for food at end of the month'

"I haven't eaten all day because there is no money for food towards the end of the month," says Sasha, who is in her 40s and a single mother of four children. She has been married three times.

"Usually, I just drink water and let the children have instant noodle or $2 packets of food," she adds, breaking into a hacking cough.

78 and nearly blind, but 'very resilient'

Confidently hobbling along his route, Mr Lee barely breaks into a sweat as he navigates across roads, up bridges and even against the flow of traffic - even though, on a sunny Saturday afternoon, all he can see are hazy outlines of trees and buildings amid shadows. He makes out the flashing green man at pedestrian crossings by squinting.

"I have been using this route for the last 30 years and I know it by heart," says Mr Lee in Hokkien as he guides this reporter along the familiar circuit - from his one-room rental flat in Redhill to the blocks of flats in Telok Blangah - that he makes three or four times a week.