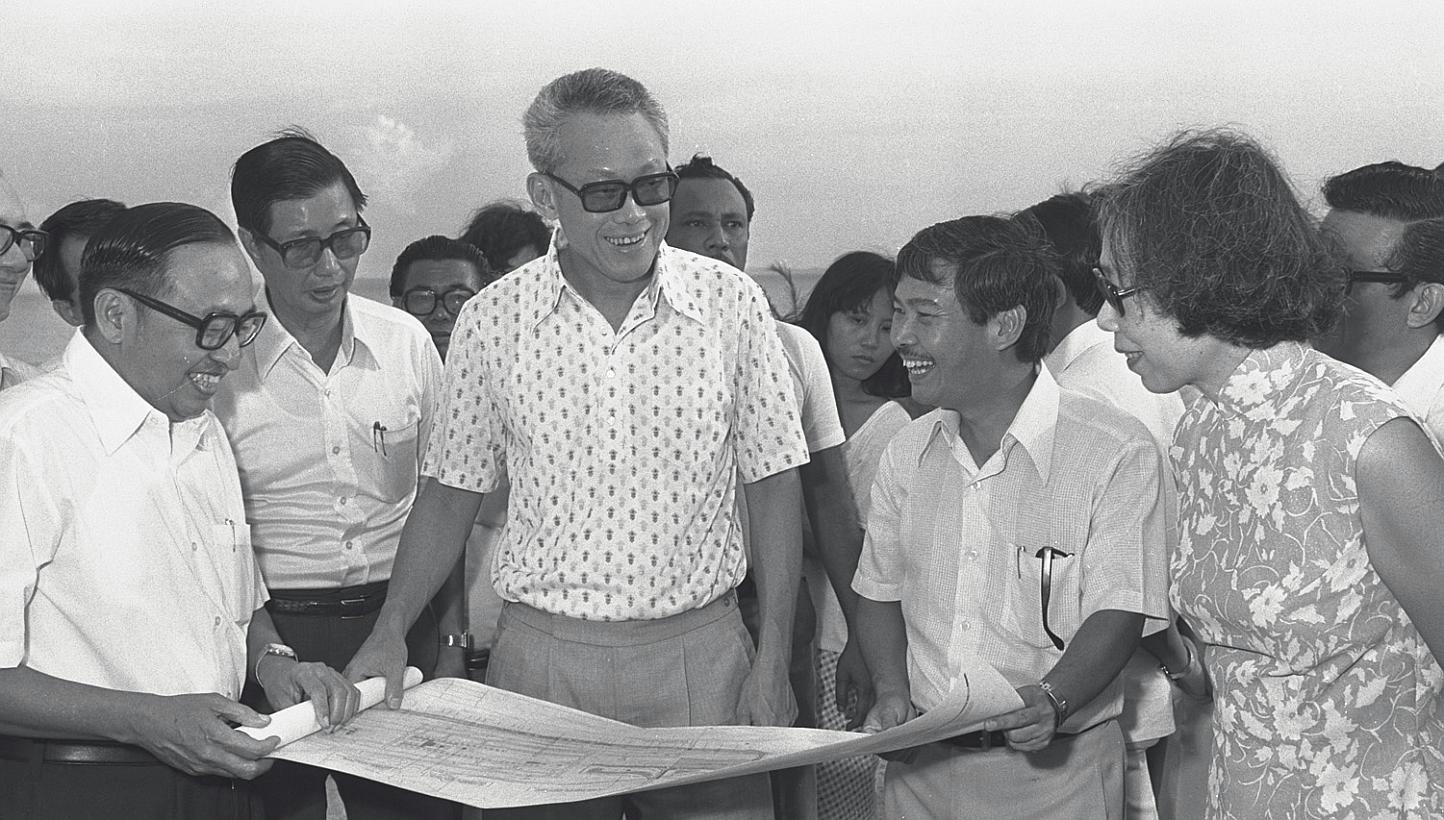

leekuanyew

Teh Cheang Wan case: No way a minister can avoid investigations

This jaw-dropping speech revealed then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew's zero tolerance of corruption. He kicks off the parliamentary session by reading out a suicide note addressed to him, written by the Minister for National Development Teh Cheang Wan, who had died suddenly a month before. Mr Lee goes on to reveal for the first time that Teh was being investigated for accepting bribes.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

This jaw-dropping speech revealed then-Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew's zero tolerance of corruption. He kicks off the parliamentary session by reading out a suicide note addressed to him, written by the Minister for National Development Teh Cheang Wan, who had died suddenly a month before. Mr Lee goes on to reveal for the first time that Teh was being investigated for accepting bribes.

JAN 26, 1987

CORRUPTION

"It is with sadness that I make this statement on the suicide of Mr Teh Cheang Wan.

On Sunday Dec 14 last year, at about 9.10am at my home, my security officer, Inspector Ho Wah Hui, told me that Mr Teh's security officer, Sergeant Richard Kua, had come, carrying a letter given to him by Mrs Teh for me. Mrs Teh had told him that Teh Cheang Wan's body was found cold in bed at about 8am.

I opened the envelope and read the undated note. It read:

"Prime Minister

I have been feeling very sad and depressed for the last two weeks.

I feel responsible for the occurrence of this unfortunate incident and I feel I should accept full responsibility. As an honourable oriental gentleman, I feel it is only right that I should pay the highest penalty for my mistake.

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) Teh Cheang Wan"

I noted "9.15" as the time I read it, on the corner of the envelope. Then I rang up Mrs Teh at her home. She gave me her account of how she discovered that Teh Cheang Wan had not awakened from his sleep. I asked if a doctor had been called to certify his death. She handed the telephone to her daughter, Dr Teh Kwan Geok, who said that they were paging for Dr Charles Toh, the physician who had been treating Teh Cheang Wan for his high blood pressure.

The daughter said her mother hoped the cremation would not be delayed by an autopsy. I said that depended on whether the doctor would certify that the death was natural. I said I would visit them later.

I immediately rang up the Cabinet secretary, Mr Wong Chooi Sen, and then my colleague, Goh Chok Tong. I asked them both to go over to Mrs Teh to render what help was needed.

At about 11.10am, Wong Chooi Sen informed me that Dr Toh had examined the body but could not certify that death was by natural causes. My wife and I went over to visit Mrs Teh at Jalan Bukit Tunggal. She was not happy at an autopsy but agreed that an autopsy had to be held. I showed her the handwritten letter by Teh Cheang Wan.

That Sunday evening, Dec 14, Dr Kwa Soon Bee, permanent secretary, Ministry of Health, told me over the telephone that the death was caused by an overdose of Amytal Barbiturate.

On Tuesday, Dec 16, I wrote a letter of condolence to Mrs Teh and to acknowledge the significant contributions Teh Cheang Wan has made in the HDB. I knew then that there would have to be a Coroner's inquest which would disclose his suicide and the reasons for it.

Members have read the evidence placed before the Coroner at the inquest on Jan 20. The director of the CPIB (Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau), Mr Evan Yeo, had seen me on Nov 21 on a complaint of corruption against Teh Cheang Wan. I asked that investigations be discreet because once people come to know that the CPIB was investigating so prominent a Minister as that for National Development, the news would spread like wildfire.

The Ministry of National Development has more opportunities for corrupt practices than any other. A Minister's reputation would be put to severe test by an investigation. Such an investigation could not be kept secret. Therefore, once open investigations had started, they would have to go on until all the evidence is uncovered to show either that the complaints are baseless, or that there is enough evidence to submit to the Attorney-General for him to place before a Court of Law for trial and judgment.

On Nov 27, the director of the CPIB wrote to me giving a summary of the evidence he had gathered and asked for my permission for an open investigation. I was satisfied that there were sufficient grounds to do so. On Nov 28, I approved open investigations.

On Dec 2, the director and his senior assistant director, Mr Tan Ah Leak, for the first time interrogated Teh Cheang Wan at the Istana Villa. They confronted him with Liaw Teck Kee, the contractor, who said that he, as the intermediary, had handed two sums of $500,000 each to Teh Cheang Wan. The director was satisfied that Liaw was a truthful witness.

He reported this to me. I asked the Cabinet secretary, Wong Chooi Sen, to ask Teh Cheang Wan to take leave of absence until Dec 31. By then the investigations would have been completed and the Attorney-General would have decided whether or not to prosecute. The investigation paper was sent to the Attorney-General on Dec 11. Teh Cheang Wan died on Dec 14.

We all know Teh Cheang Wan. He was a man of considerable ability. Behind his diffident manner and demeanour and his Hokkien-accented ungrammatical English was a sharp clear mind. After open investigations started, we did not meet. I received a letter from him dated Saturday, Dec 13, 1986, that morning. The Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of National Development, Mr Koh Cher Siang, was on overseas leave and was recalled by Teh Cheang Wan to vet his draft and correct his grammar. Mr Teh's personal assistant typed the letter before he signed it.

It was identical in terms to a letter he sent to the director of the CPIB on the same date. In his letter he denied the charge that he had on two occasions been given half a million dollars of which he kept $400,000 and gave Mr Liaw, the contractor, $100,000. He went on to write:

"If I am brought to trial, the very process of it, which will be painful and long, will certainly be the end of me even if I am found innocent."

Sir, there is no way a Minister can avoid investigations, and a trial if there is evidence to support one. Teh Cheang Wan chose death rather than face a trial on the charges of corruption which the Attorney-General had yet to settle. The effectiveness of our system to check and to punish corruption rests, first, on the law against corruption contained in the Prevention of Corruption Act; second, on a vigilant public ready to give information on all suspected corruption; and third, on a CPIB which is scrupulous, thorough, and fearless in its investigations.

For this to be so, the CPIB has to receive the full backing of the Prime Minister under whose portfolio it comes. But the strongest deterrent is in a public opinion which censures and condemns corrupt persons, in other words, in attitudes which make corruption so unacceptable that the stigma of corruption cannot be washed away by serving a prison sentence."