Targeted ops, on-site testing tools among Singapore Food Agency’s moves to boost food safety

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Food safety inspector Ernest Chua demonstrating how he carries out inspections in a restaurant kitchen.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

SINGAPORE – When food safety inspector Ernest Chua issued a suspension notice to the licensee of a central kitchen, the man got upset and refused to comply, until a few hours later.

In that incident in 2022, a food item was found to contain additives that flouted regulations, drawing a period of suspension from the Singapore Food Agency (SFA).

For Mr Chua, 30, that enforcement action was among the first targeted operations – a new inspection regime that SFA started in May 2022 – that he had been sent on.

Adding to routine inspections, these operations zero in on food manufacturers, stalls, eateries and bazaars that are more likely to have food safety lapses.

These establishments are chosen based on data such as which licensees have a track record of failing inspections and which establishments have had food-borne outbreaks, as well as public feedback.

From May to December 2022, close to 10 per cent of the 1,903 licensees targeted were penalised for breaching regulations – an enforcement rate more than thrice the average 2.8 per cent in 2019 for routine inspections.

Data from 2020 and 2021 was not used because a number of food establishments were closed during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In mid-2022, SFA also rolled out a van furnished with equipment to rapidly detect biological, chemical and radiological hazards on-site. The mobile laboratory has supported targeted operations tied to major events, such as the 2022 National Day Parade (NDP) and the Chingay parade in February, to ensure that the food provided by caterers was safe for consumption.

These SFA moves, which come amid more food imports and food establishments set up over the years, pave the way for inspectors to be more efficient in their work and for the agency to focus resources on potential offenders.

In 2022, 53 targeted operations were carried out on 1,903 licensees. One operation usually covers multiple businesses, with inspectors looking out for hazards such as pest infestation, unhygienic processes, pathogens and unpermitted ingredients in food by taking samples.

Mask wearing and tray returns at coffee shops are also tracked through targeted operations. In September 2022, inspectors went to 40 coffee shops and foodcourts

Rapid testing at hazard’s doorstep

The invisible culprits behind food poisoning and contamination – bacteria, viruses and chemicals – can be detected only through lab tests. It can take a few days to fully analyse food samples and swabs at the National Centre for Food Science (NCFS).

But rapid-test equipment in SFA’s van can help scientists identify food-borne pathogens within two hours of collecting swabs from food preparation areas, chopping boards and knives, among other surfaces that are in contact with food.

SFA’s van is furnished with machines and equipment to rapidly detect biological, chemical and radiological hazards on-site.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

Food-borne pathogens that NCFS scientist Chan Siew Herng looks out for include Salmonella, Norovirus – the most common cause of stomach flu – and Vibrio bacteria from raw or undercooked shellfish.

Dr Chan, 36, who handles the microbiological tests in the van, said: “By bringing (quicker) food-testing capabilities down to the site, (the team can check) if a food establishment has any hygiene lapses in a timely manner. Then we can immediately recommend mitigation for the risks identified.”

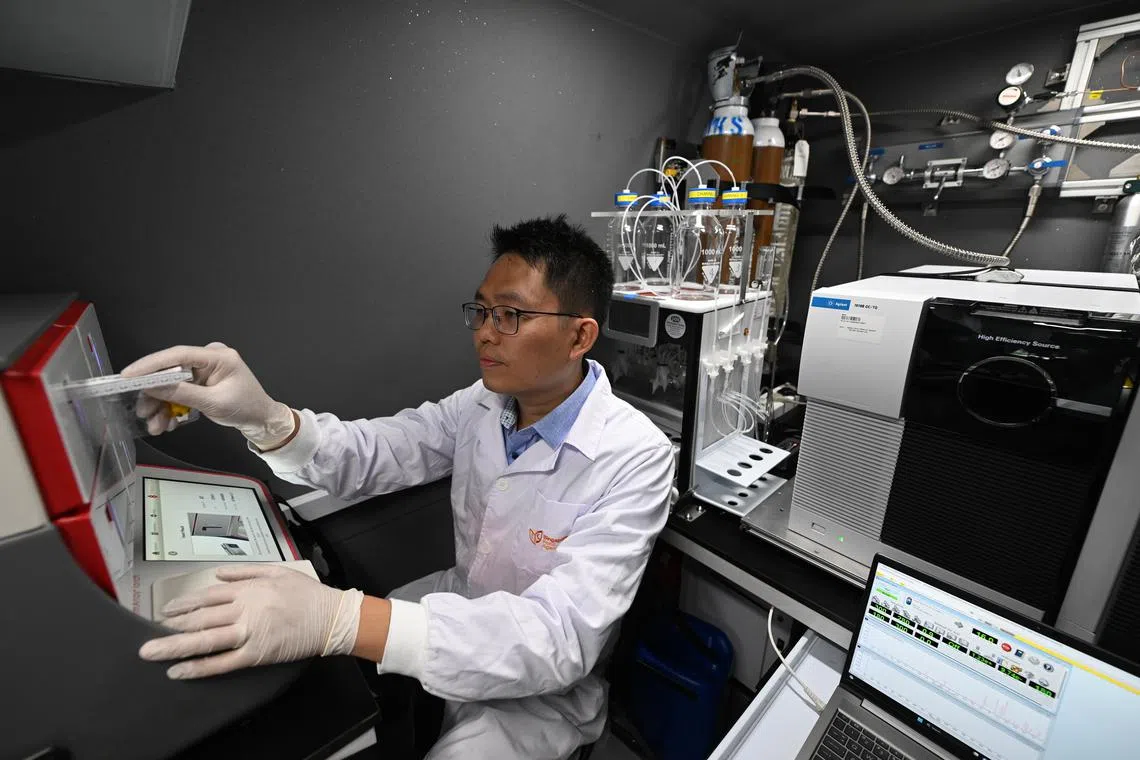

Dr Chan Siew Herng loading a processed sample into a multiplex PCR (polymerase chain reaction) machine in the van. The sample could include swabs of food preparation areas, chopping boards or knives. Less than two hours are needed to detect any pathogens that are present.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

Three of the 52 swabs taken from caterers at NDP tested positive for various food-borne pathogens, said SFA. The affected caterers were told to immediately disinfect areas, discard worn-out utensils and step up hand hygiene.

SFA’s van also houses equipment to test for chemical hazards, such as an ammonia gas leak at a slaughterhouse or illegal imports of fruit and vegetables that contain excessive pesticide residues. Prompt testing of suspicious food items also allows inspectors to hasten enforcement.

Inspectors educate, too

When staff at food businesses spot inspectors from afar, many become guarded. Mr Chua said: “When they see me, I don’t feel welcome... that’s the thing about us in our job. Some staff who may not know we are really from SFA would challenge us by asking: ‘Who are you? What are you here for?’”

In the 2022 incident involving the central kitchen in the north, harsh words were hurled at Mr Chua and his colleagues, and at one point, the licensee told his staff to take videos and pictures of the inspectors while they were carrying out their work.

“He was very uncooperative from the start. It didn’t help with other workers becoming very upset and saying: ‘Why are you doing this to us?’” recalled Mr Chua.

Food safety inspector Ernest Chua demonstrating how he carries out inspections in a restaurant kitchen. The torch can be used to look for pests.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

There were also times when he had to deal with unhappy customers who insisted that they got food poisoning from a particular eatery, even if it had passed an inspection.

Mr Chua, who has been a food safety inspector for 2½ years, said he does not want to be seen only as someone who “saman and saman”, referring to the Malay term for dishing out fines or penalties.

“We are always portrayed as the bad guys in eating houses,” he explained. “So we will praise them when they (adopt) good food safety practices. One part is being an enforcer and another part of our role is being an educator.”