ST Explains: What are bilateral carbon credit pacts, and how do they benefit S’pore?

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Large greenhouse gas emitting companies in Singapore can eventually buy these credits to offset up to 5 per cent of their carbon tax.

ST PHOTO: GIN TAY

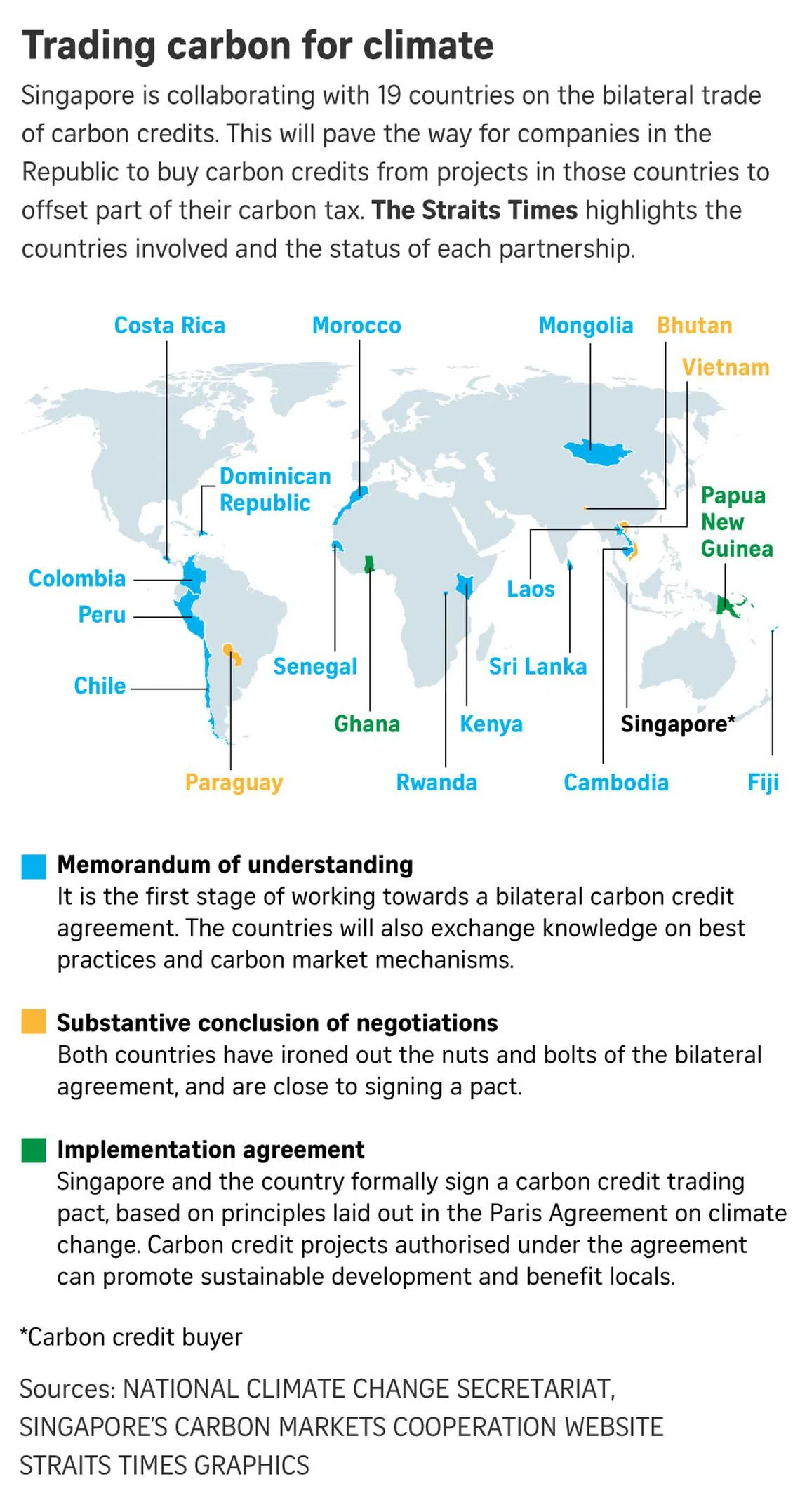

SINGAPORE – On July 9, Laos became the 19th country to collaborate with Singapore on carbon credits,

Large greenhouse gas emitting companies here can eventually buy these credits to offset up to 5 per cent of their carbon tax, which is set to increase by 2030.

The Straits Times breaks down the complex concepts behind carbon trading and what it takes to form carbon credit pacts in line with the Paris Agreement.

What are carbon credits and how are they generated?

Carbon credits refer to permits or certificates that allow a company’s operations to generate a certain amount of carbon emission.

One carbon credit represents one tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) that is either prevented from being released into or removed from the atmosphere.

Carbon credits can be generated through projects that take in CO2 from the atmosphere, or through measures taken to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases released. These include carbon capture technologies, forest restoration, swopping pollutive cookstoves for cleaner ones, and renewable energy projects.

Not all projects can make the cut. In late 2023, Singapore released a set of eligibility criteria

For example, in calculating the amount of emissions removed by a mangrove planting project, the calculations must be made in a conservative and transparent way, and measured and verified by an independent third party.

The National Environment Agency also released a list of specific types of projects or methodologies that Singapore is willing to accept, based on existing carbon crediting programmes. These include international carbon credits that come from offshore wind technology and cleaner cookstoves.

Internationally, a recent oversupply of carbon credits from renewable energy projects failed to deliver additional climate benefits, noted Ms Melissa Low, a research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions.

How far along is Singapore in trading carbon credits?

Of the 19 countries Singapore is collaborating with on carbon credits, two have finalised bilateral agreements with Singapore so far – Papua New Guinea and Ghana. These are known as implementation agreements.

This means companies here can buy carbon credits to offset up to 5 per cent of their taxable emissions, provided the carbon projects in Papua New Guinea and Ghana meet Singapore’s eligibility criteria.

Steps must be taken to prevent the double-counting of emission reductions in both the carbon credit buyer (Singapore) and the host country’s national greenhouse gas inventories.

And in each agreement, climate adaptation for the host country and the mitigation of global greenhouse gas emissions must be prioritised.

For example, carbon credit project developers must contribute 5 per cent of their share of proceeds from authorised carbon credits towards climate adaptation in Ghana.

Project developers must also cancel 2 per cent of carbon credits at first issuance, so that those credits will not enter the carbon market. The 2 per cent has the sole purpose of reducing emissions.

These elements are strongly encouraged under Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement, which governs the bilateral trade of carbon credits between countries.

Of the remaining 17 countries, Singapore has concluded negotiations on similar carbon credit schemes with Vietnam, Paraguay and Bhutan. The next step will be to sign the agreements.

Singapore has also signed memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with other countries such as Laos, Indonesia and Fiji, with the intention of collaborating on carbon credits.

A fair amount of negotiations takes place before an MOU becomes a bilateral agreement, said Ms Low.

“This would include an assessment of the respective countries’ climate targets and level of ambition and whether the respective countries have arrangements in place to transparently report on their greenhouse gas inventories,” she added.

It took 10 months for Singapore and Ghana to conclude negotiations on their deal.

As at May, only one carbon credit transaction under Article 6.2 has taken place between Thailand and Switzerland.

According to a carbon market explainer by The Nature Conservancy, such international transactions will take time, and bilateral agreements are only the first step.

“Countries still have several additional steps, such as providing letters of authorisation, complying with reporting requirements and, once the project is concluded, starting monitoring and verification processes. Only after the first monitoring cycle is completed can the first issuance and first transfer (of credits) take place,” stated the report.

Checks by ST in January revealed that Singapore companies looking to buy carbon credits from Papua New Guinea must wait longer for eligible projects that are of high quality, as none of the available credits for sale currently meets the criteria set by the Singapore Government.

On June 20, it was announced that more than 100,000 improved cookstoves will be distributed to communities in Papua New Guinea that still rely on open-fire cooking. This project was approved by carbon crediting programme Verra.

The project’s developer, Tasman Environmental Markets, said it is working with Singapore and Papua New Guinea to finalise the approval of its project under both countries’ carbon credit agreement.

In July, Verra suspended 27 cookstove projects over allegations of over-issuance of millions of carbon credits, Ms Low pointed out.

“So, it remains to be seen if cookstove projects in Papua New Guinea will eventually be eligible for use under Singapore’s framework,” she said.

Ms Low added that the authorities are organising a business mission to Ghana in July, and this may help companies in Singapore explore opportunities there.

How does carbon trading benefit Singapore and the host country?

Carbon markets help to channel funds to nature-based and underfunded forest conservation projects that would not otherwise have been implemented due to factors such as insufficient policy and economic incentives.

Carbon projects can further the sustainable development of host countries, benefit local communities in terms of job creation and access to clean resources, and improve their energy security. Environmental pollution can also be reduced while protecting the rights of indigenous groups.

Temasek-backed investment platform GenZero has been investing in a forest restoration project in the Kwahu region of Ghana. It involves replanting degraded forest reserves, including growing cocoa trees sustainably in shaded farms to shield the plantations from disasters and pests.

Jobs in farming and agroforestry training will be created, and there will be new income opportunities for indigenous communities. The verification of carbon credits from the Ghana project will begin in 2028.

As for Singapore, buying carbon credits can benefit carbon-tax-liable firms as the tax is set to increase. The carbon tax in 2024 has increased to $25 per tonne of CO2 emissions, up from $5 per tonne previously. By 2030, the tax will eventually reach $50 to $80 per tonne.

Companies can potentially cut their carbon tax liability if they can procure carbon credits that are lower than the prevailing tax rate of $25 per tonne, noted Ms Low.

Being an alternative-energy-disadvantaged country, Singapore can tap carbon credits to meet its national climate targets, also known as NDCs.

But this will have trade-offs for the host country. The more credits a host country exports to Singapore, the less mitigation can be claimed against its own climate goals, stated The Nature Conservancy explainer.

“Even when domestic frameworks are in place, a more complex issue will arise as host countries define what sectors, how many units at what price they could transfer internationally without undermining the achievement of their NDCs,” the report stated.

Correction note: The story has been edited for clarity.